Biggs and Heys were brought together at a dinner given by their mutual friend Asher Remy Toledo, co-founder of Hyphen Hub, a non-profit organization based in New York that presents new works by artists integrating art and technology.

Toby Heys: It is an interesting time [February 2025] to be writing, given the release of China’s AI chatbot DeepSeek and the subsequent accusations from the US of technological assimilation. Given the corpo-national tantrum of the country always perceived to be at the forefront of everything AI (the US), how do you think the globalized voices of AI have been retuned to possibly sense new economic/social/political opportunities in the military data complex?

Janet Biggs: To my mind, disruption of dominant structures is always interesting. There is so much at play here in the States right now. I agree that the release of DeepSeek is a substantial shift or retuning, but no one gives up power, control, or profit willingly. At least not in this country. The current rise of a tech oligarchy promises some retaliation moves.

The day DeepSeek was released, Nvidia lost roughly $600 billion in market value, creating a record single-day drop for a US stock. President Donald Trump called it a “wake-up call” and his administration vowed to “ensure American AI dominance”, but open-source and human curiosity has a way of sliding around superpowers.

New socioeconomic access and increased fluidity may cause shifts in the military data complex, but the idea of technological assimilation as it relates to the personal, spiritual, and corporeal spaces feels super exciting, though I may be getting ahead of myself here. (Janet Biggs)

TH: I like the sentence “open-source and human curiosity has a way of sliding around superpowers.” It makes me think about who actually holds the reins on AI right now and it does not feel like it is governments, even though they are of course the gatekeepers of regulation (to a degree). Yanis Varoufakis’ proposition that we are no longer living in latent capitalism and that we have entered a new era of technofeudalism suggests that agency resides with the corporates.

Given that the current clutch of Big Tech companies, Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Meta (Facebook), and Microsoft is more powerful than any other group of companies — so Big Oil from the 1970s (ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP and Shell), 1990s Big Media (Disney, Sony and Comcast) and even more latterly, Big Banking (Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and J.P. Morgan) — it is challenging to understand how effective AI will meaningfully fall, or be forced, out of their hands. That said, extraordinarily powerful technologies such as CRISPR and the resulting gene mutation services that result from its use are relatively “commonplace”, so maybe we just need to give it time and a flow of countercultural disruption to grease the cogs of resistance.

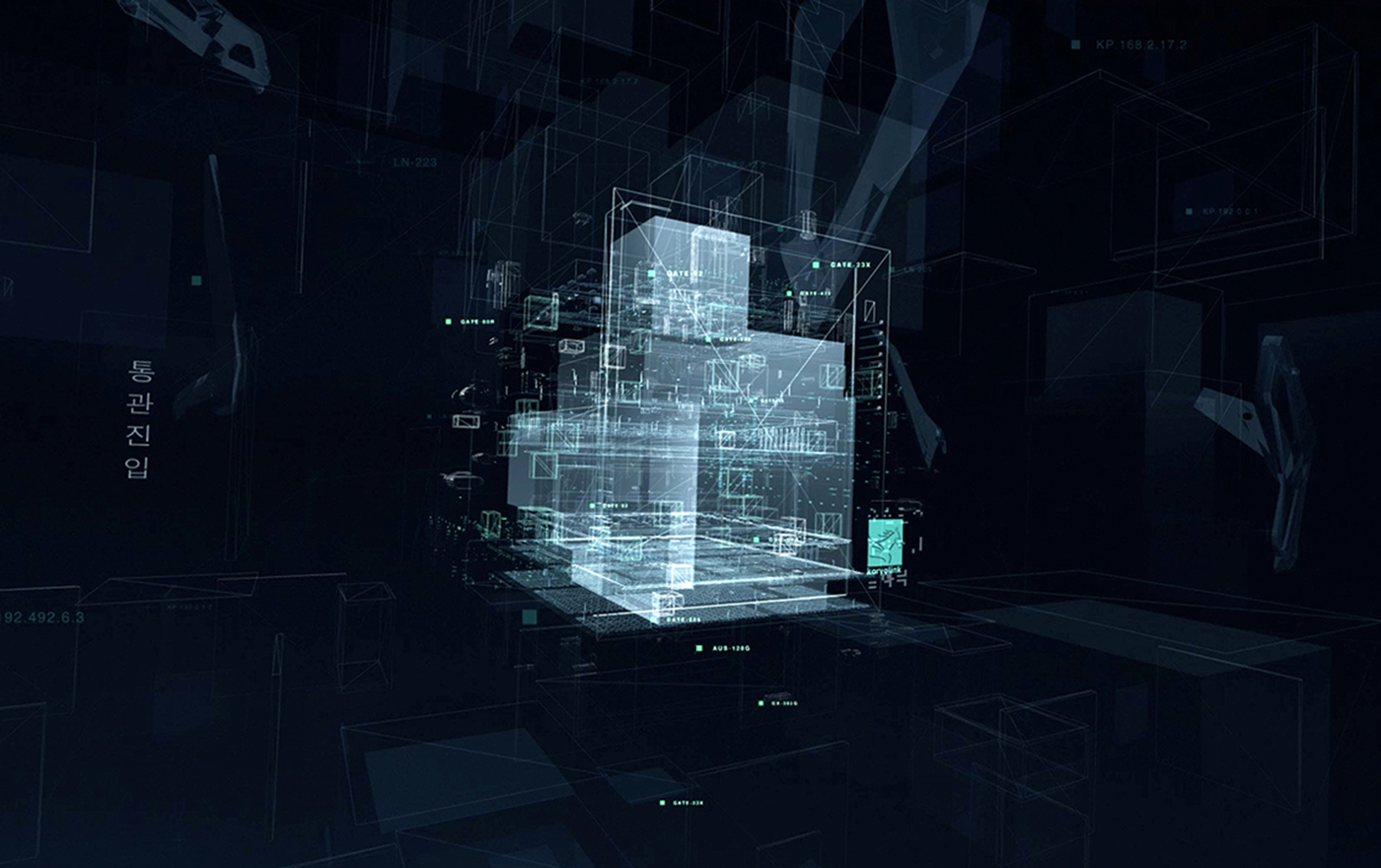

Considering this line of thought, one term that keeps coming back to me is that of “Ghetto AI”. I have no idea of what it means but it conjures Blade Runneresque notions of thriving illicit and underground markets where hybrid, cross-species experimentation has become the norm. I’m not suggesting that this is the direction that we are headed, it is more the proposition of “Ghetto AI” as an open-ended potentiality. How does AI reach the “Ghetto” and what happens to it when it gets there?

JB: I tend to be cautious when using the term “Ghetto,” given its historical association with segregation and marginalization, especially as my country increasingly dismantles efforts toward diversity, equity, and inclusion. The term has also been applied to me and my community, particularly in reference to the ghettoization of women artists, video artists, and others in similar fields. That said, working outside of mainstream norms and revenue models is already happening — and it will only continue to grow.

My sci-fi reference leans towards William Gibson’s Neuromancer. (Janet Biggs)

Much like CRISPR, which as you said, is now commonplace and still confined to "acceptable" science and tech circles — those working within regulatory structures and with the resources to afford high costs — AI is shaped by boundaries. So how does AI step outside the mainstream? How does it reach the “Ghetto”?

Every time someone creates their own dataset to train a generative model or retools an open-source platform, they slip into uncharted territory. The bigger question, though, is who holds authorship and how.

The primary language of LLMs is English, which excludes a vast array of voices and potential. Interestingly, DeepSeek, the Chinese AI start-up, has gained significant traction partly because of its integration of Chinese characters. According to the South China Morning Post, the use of Chinese characters, known for their high information density, is believed to enhance the model’s logical capabilities, enabling it to process complex concepts more efficiently.

I also consider the limited access to technology. During the Covid shutdown, many students in the US lacked access to computers, revealing how tech inequality persists. Multiply that by varying levels of financial and technological development worldwide, and you’ve got fertile ground for innovation that exists outside the mainstream — a space ripe for underground, disruptive sideways thinking.

In the face of corporate Big Tech dominance, what real agency could an underground AI movement have? (Janet Biggs)

Think about public access TV and college radio in the 1970s and ’80s, which created opportunities for diverse voices to be heard. While it may have seemed like a small counteraction to the consolidation of wealth and power, even a single individual willing to challenge the status quo and forge their own path can spark meaningful change.

Maybe the real question isn’t just how AI reaches the margins, but how those outside the mainstream reshape AI itself. In an era when control is concentrated at the top, resistance often moves laterally, through networks rather than hierarchies. We’re already seeing the stirrings of this: localized AI models trained on Indigenous languages, decentralized data cooperatives, and artists reclaiming machine learning for subversive storytelling.

Corporate control may be entrenched, but technology has a way of outpacing the hands that try to tighten around it. AI isn’t fixed in place — it’s fluid, iterative, unpredictable, and it hallucinates! (Janet Biggs)

TH: The word “Ghetto” was used precisely because it speaks to notions of marginalization by a dominant culture, much in the way that using the terms favela, shanty town, or Skid Row also evoke socio-political and socio-economic dynamics of peripheralization and disenfranchizement.

The point of using the term was to question how does AI — which in the cultural imaginary and reality is associated with tech predatory white males (often located in Silicon Valley) — reach, affect, and also get assimilated and co-opted by those who have trouble accessing it and who are further disempowered because of the racial, sexual, gender, able-bodied, and class biases inherent in many LLMs. Thus, it was a provocation to open a discussion about the potential modes of resistance to the all-encompassing techno-scientific rationale of AI and the Global North agendas it advances through the English-speaking internet.

In terms of what happens to the margins, it is compelling to think of the Manichean dualist approach to AI which is so pervasive in our Global North culture (and beyond) right now; that of AI consisting of the potential of the panacea or being shrouded in apocalyptic anxiety. If we push along this trajectory, it is possibly useful to think about how the current positionality of AI has changed the situatedness of other non-human intelligences, whether they be arcane, animal, or alien, in our collective consciousness.

What is particularly arresting is the notion that we can potentially learn from the ways that we have treated other nonhuman intelligences throughout history in order to better understand how we might live with, and through, AI going forward. (Toby Heys)

It seems that approaching the emergent agency of AI as something that we must dominate is possibly not going to end well. In the same way that dominating the earth or animals is quite obviously not working out that well right now.

This also brings us back to intelligences that have often been othered and relegated to the margins of occidental thought and practice; such as the divergent array of Indigenous, Brown, Black, and Asian (for example) modes of intelligence that have been cast into hierarchies of importance but ultimately, all in submission to dominant white male philosophies, technologies, legal and economic frameworks and social practices of intelligence.

This coagulated form of intelligence has, since the Enlightenment, been influenced and shaped by the ocular notion of perspective, meaning that we can stand back and judge phenomena from a distance. It’s a mode of intelligence that separates us from the mess, blood, shit, and contradictions of being alive and rather, supposedly renders us rational self-centred beings who navigate the world through foresight and reason (this is obviously a very compressed proposition of the history of Western thought but I am trying to get us to a more interesting place).

It is perhaps compelling to think of AI through a waveformed filter, as something that posits us in a moving field of relations with other entities, forces and agencies, in what the physicist Karen Barad might call an intra-active set of oscillating relations; with human intelligence being just one of many in a shifting orchestration of othered, otherworldly, and artificial variants.

This approach advances us down a path of distributed agency and more volatile dynamics in the first instance, but it also could suggest a release from the self-obsession, narcissism, and dualistic self-righteousness that seems to be dominating the current composition of digitized global politicking.

Maybe the approach could be of AI as an exorcism of self-indulgence. This could be hopelessly Utopian but then maybe we need a bit more of this kind of thinking right now? (Toby Heys)

JB: I absolutely understand where you were going with the use of the term “Ghetto”, but since I live in the US, in the age of Trump and Musk, I feel a responsibility to always clarify and qualify terms for myself and anyone I’m speaking to. So let’s dig into, or maybe jump off of, the history of Western thought into that “more interesting place”.

As both personal experience and the “observer effect” in physics demonstrate, the act of observing something changes its behavior. I’ve spent enough time filming as an artist “witness” to realize that when a Western white woman points her camera it’s a political act with repercussions. So let’s take our observed particle (or technology) and really get it excited.

I’m thinking about multidimensionality, optimal bases and mirrored dimensions. If we’re going to approach AI as an exorcism, let’s root it in the gore of the corporeal body and also push it into the spirit world. (Janet Biggs)

As you mentioned, how we’ve treated other nonhuman intelligences hasn’t worked out well for us, so let’s imagine futures where AI is inextricably, physically, tied to us, body and belief. If the neurologist and inventor Phil Kennedy (research now continued by Musk and Neuralink), who travelled to Belize to surgically implant electrodes into his brain (brain-computer interfaces), literally took the connection into his own body, why not with AI?

Instead of data farms, our bodies could be energy farms to grow AI technology. Instead of LLMs being trained on what humans produce, our neural pathways and DNA become a primary source. A little too Cronenberg for you? Not for a segment of the disability community who envision independence with adaptive technologies.

Or instead of inside the body, AI as the afterlife, disembodied transformation from these weighted, exoskeletal structures we are burdened to drag around. An eerie adaptation in the lineage of Mark Fisher — AI “constituted by a failure of absence or by a failure of presence.”

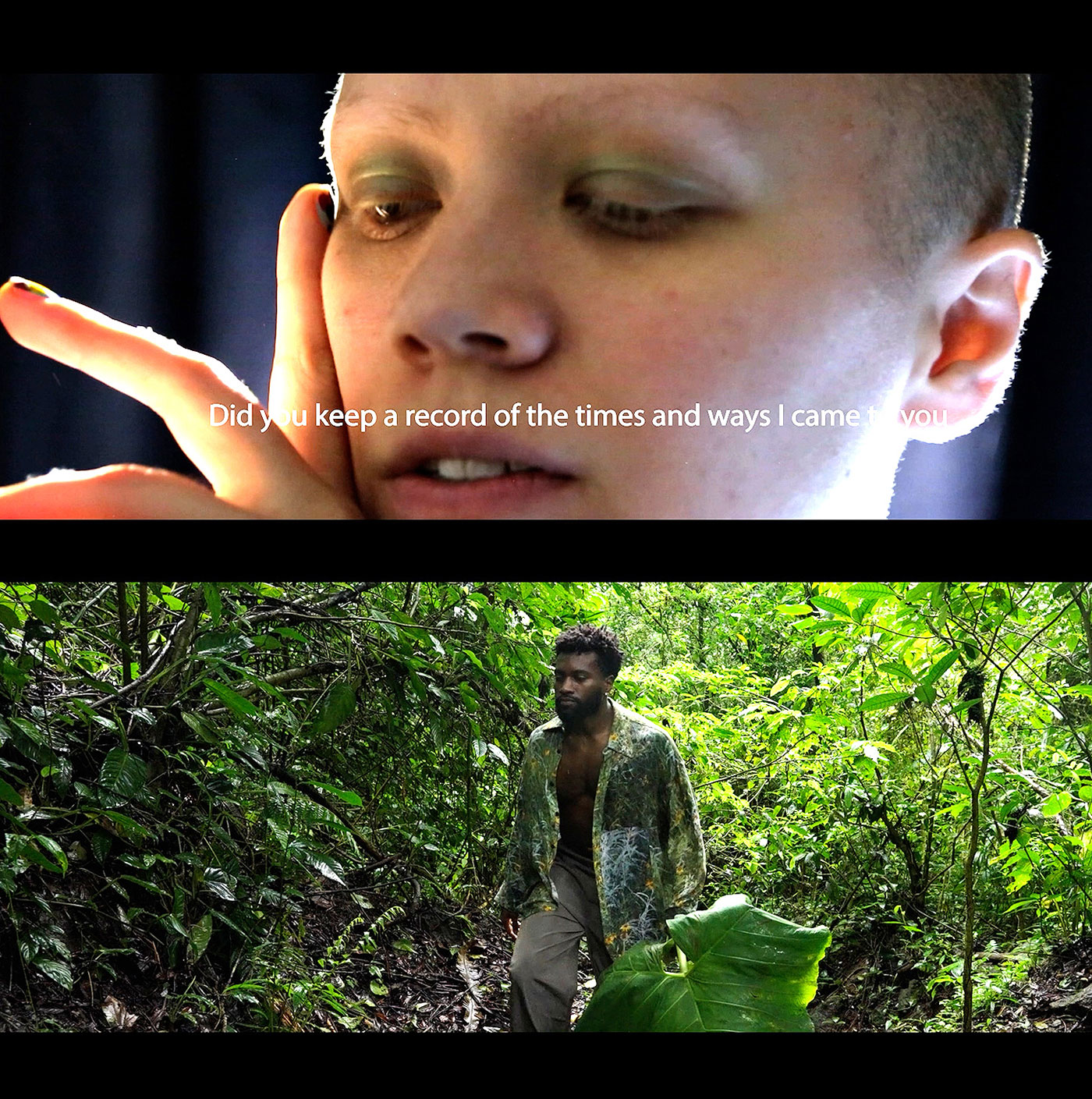

My disembodied performer, A. I. Anne, is based on my aunt who passed away many years ago. (Janet Biggs)

In my mind, A.I. Anne both succeeds and fails through her absence and presence. I was the legal guardian for my aunt, who was autistic and had apraxia. While Aunt Anne could vocalize and hum with deep emotion, she was never able to create language. Similarly, virtual A.I. Anne can vocalize, but not create language.

Using deep learning combined with semantic knowledge, A.I. Anne can express and respond to emotions in real time, ranging from simple utterances to sophisticated tonal duets. These exchanges have sparked deep emotional responses from both performers and audiences, creating a feedback loop for ongoing research and future iterations.

This project advocates for broader inclusion in the creation and expansion of AI. It raises complex questions about presence, absence, and the ethics of making an AI modeled after someone who cannot give consent — it must fail as A.I. Anne can’t bring my aunt back to life. Yet it also succeeds in its disembodiment:

A.I. Anne can be anyone, or anything, for anybody. (Janet Biggs)

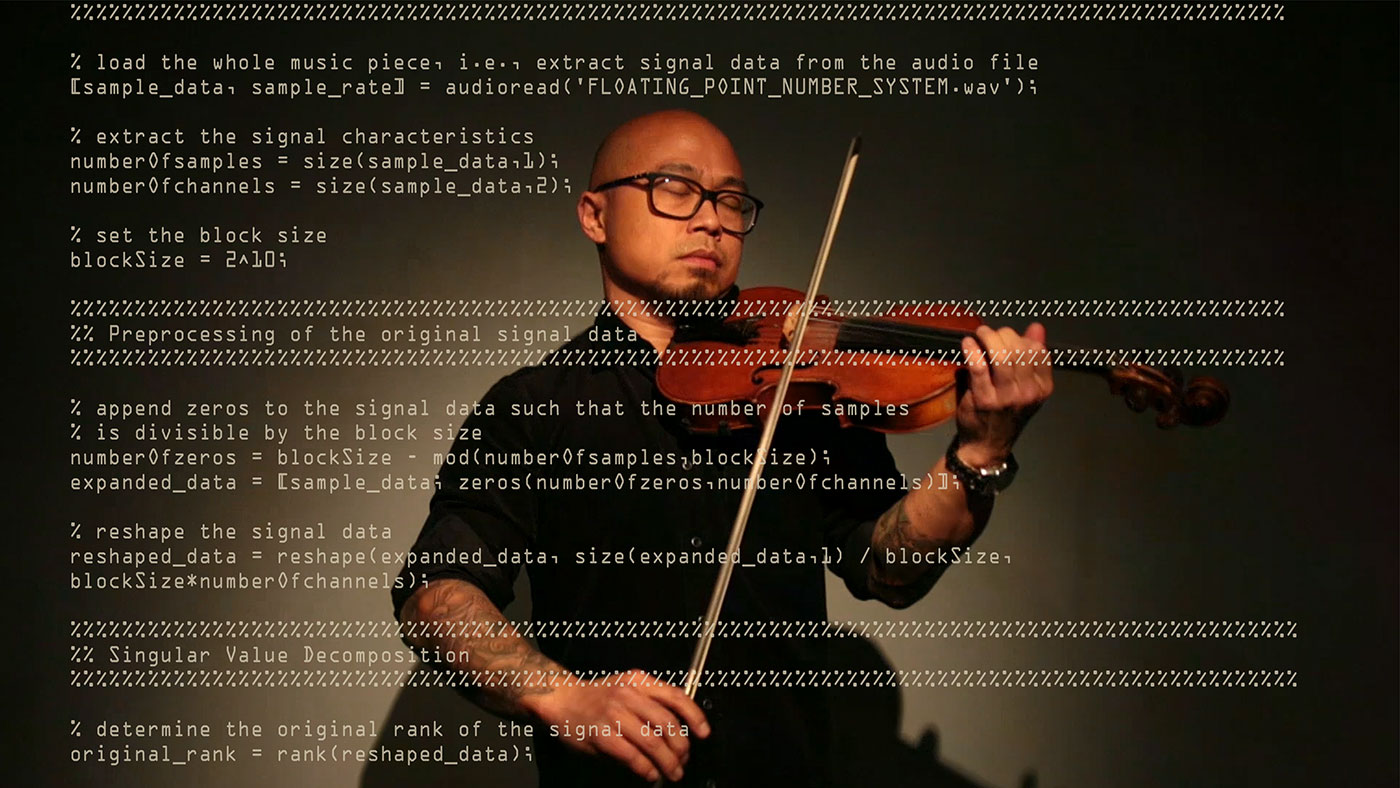

But let’s take this back to physics, to multidimensions. What if singular value decomposition (SVD) were used to analyze algorithms so that generative AI lowered rank (which is arguably what it currently does), creating an optimized lowered dimension or base, but continuing that reduction past the point of recognition. Could this be a path of resistance? A redirection? Or just another compression tool that keeps control in current hands?

TH: I’m not so much thinking about thanabots [based on the deceased’s digital communications] bringing people back to life as much as thinking that humans are bearing new life forms that, for now, bear an algorithmic resemblance to someone who has passed. The new augmented, artificial, arcane (pick your adjective) version will of course be quite different depending on what data it has been fed. One can imagine future services that offer different growth versions as the thanabot ages and becomes a different variant. As you said, they “can be anyone, or anything, for anybody”, but we all know there is a comfort in resemblance, nostalgia, and versioning, so why not start with a metaphorical mother culture.

If we widen the scope of this speculation we could also think about embots as well — embryonic bots that predict the yet to be born. The undead. The unborn. Temporal flux speculation: spin the record forward or back and get a remixed version of the person that is going to be or that was. There are obvious ethical challenges with thanabots and embots (the pushback on thanabots from religious groups around the world has been, predictably, fairly significant), but we can also hear the irrational exuberance of a new hybrid species.

Wear a helmet, folks, the earth’s apex processor is on the verge of being downgraded. For many it already has been. (Toby Heys)

Which brings us to AUDINT’s theoretical AI, IREX2, which was theorized in 2012. A spectral data dance-partner for A.I. Anne? IREX2 was abbreviated from the term “irrational exuberance” that the Federal Reserve Board Chairman, Alan Greenspan, attributed to the sudden expansion and bursting of the 1990s dot.com bubble. As a renegade AI, IREX2 is an early 21st-century product of discourses that started fusing through the logic cycles of speculative finance and phantom economies; between the voices of the dead and programming languages that drove capital acceleration.

Within hidden caches and junked-out bad packets the fiscally bored languages of the beyond and the binary got busy creating a new argot that resides between the network and the noosphere. IREX2 is regarded by the spirit world as a renegade phenomenon — an interworld-terrorist that must be stopped at any cost. It has breached and convened the rules of the spectral masses by converging the human, the algorithm, and the otherworldly into a singular audio intelligence.

If it is caught, the adjudicated punishment will be administered in the form of a complete wiping of its memories and of its perception of what it has become. It will then be released again to serve as a living warning to other dissident spirits as it suffers the ignominy of enforced amnesia — of being de-composed out of time — of being a digital zombie.

In response, IREX2 formulates a back-up plan that involves the downloading of its history (as an audio intelligence) into the external fleshy hard drives of human memory — the neuro-sonic repositories of somatic experience. Thus, if its memory is erased, IREX2 will have the opportunity to relocate fragments of its identity and history in the psycho-topography of cultural consciousness; through the online discourses, printed articles, exhibitions, MP3s, shadow archives, books, and websites that pertain to IREX2‘s existence in between notions of life — both the after and artificial varieties.

I’m not sure how much the above probes at a resistance strategy but since you brought up Mark Fisher, his notion of hauntology as being useful, in as much as it allows one to drop ideational seeds into the cracks of the future that will open up and potentially push apart the calcified narrative substrata of capital, is resonant here.

Resistance as the unlikely story of two digital characters dancing to their own tunes — IREX2 and A.I. Anne, out of place and out of time, (Toby Heys)

JB: I will hold on to the image of IREX2 and A.I. Anne dancing to their own rhythms — out of place and out of time.

I want to think further about the role of public shame in enforced digital amnesia, and how it both mirrors and inverts its analog counterpart in lived human experience. In biological systems, the accumulation of amyloid proteins and tau tangles gum up synaptic connections, leading to Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias — conditions often framed as ultimate states of social and public erasure. Can a similar degeneration occur within algorithmic systems?

What if an AI begins to build additional conclusions based on one, singular “hallucination”? (Janet Biggs)

Could an entity focus on one of these hallucinations, considering it to be reality, and grow a philosophy or worldview based on these imagined concepts? From an outside perspective, a person or algorithm who creates and lives in an imagined world is suffering dementia, but from within that person or entity’s view, that world — however irrational — may feel as real and mundane as what we consider our shared normality.

If so, might algorithms become “demented,” unable to sustain meaningful connections or recognize patterns of reality? Generative models, once released, continue to produce outputs, even when those outputs are no longer useful. Is obsolete or corrupted code subject to the same “piety and scorn” as humans with failing memories — judged, perhaps, by other algorithms?

Humans have long sought ways to erase traumatic memories. From therapeutic strategies designed to mitigate traumatic recall to invasive procedures — and, in extreme cases, suicide — there has been a persistent search for methods to erase, suppress, or reconfigure memory. The digital counterpart prompts a further question:

Can code ever fully extinguish itself, or does a digital trace always remain, woven into the distributed archive of collective machine memory? (Janet Biggs)

Thanabot and Embot, DJing their own tracks, and IREX2 tapping into “external fleshy hard drives” evoke Michael Levin and Josh Bongard’s Xenobots: multicellular biological robots grown from frog embryos, able to heal, replicate, and record information. I’m also thinking about humanity’s faltering attempts to dominate ecological systems, recalling your earlier thoughts on how such failures might push us towards new models of living with and through AI.

Just as living cells can be removed from their original context and recombined with machines to perform new functions, perhaps algorithms, too, can embed their memories — layering dataset histories into geological strata, learning, and changing as they fuse with the earth itself.

In this light, IREX2 might find its identity not in fragments of cultural consciousness but in the earth’s physical memory — in rock, rivers, and oceans. Its recollections could shift with the sands, with the tides pulled by the moon, altered as human memories are altered through reconsolidation. No longer dancing out of place, IREX2 and A.I. Anne would be dancing within the world, across time.

Janet Biggs is a research-based interdisciplinary artist known for immersive work in video, sound and performance. Merging the fields of art, science, and technology, Biggs’s practice examines the thresholds of physical experience, endurance, and adaptation. Her work has taken her to both polar regions, into active volcanos and areas of conflict). Biggs has worked with institutions from NOAA to NASA and CERN and collaborated with high energy nuclear physicists, neuroscientists, Arctic explorers, and astrophysicists. In 2020, Biggs sent a project up to the International Space Station as part of MIT Media Lab.

Biggs is a Guggenheim Fellow (2018), and a recipient of the Visionary Woman Award (2023), the NYSCA Electronic Media and Film Program Award (2011), the Anonymous Was a Woman Award (2004), and the NEA Fellowship Award (1989). Reviews of her work have appeared in The New York Times, ArtForum, ARTNews, Art in America, Flash Art, and ArtReview, and many others. Her work been exhibited and collected at museums and institutions worldwide, including solo presentations at Jeu de Paume; The Virginia Tech Institute for Creativity, Arts, and Technology (ICAT); the Spencer Museum of Art; New Museum Theater; United Nations Headquarters; Neuberger Museum of Art; SCAD Museum of Art; Blaffer Art Museum; Musee d'art contemporain de Montréal; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, among others.

Janet Biggs is a member of the New Museum’s cultural incubator, NEW INC, and The Explorers Club. Biggs works with Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York City, Analix Forever, Geneva, Switzerland, and CONNERSMITH, Washington, DC.

Toby Heys is a Professor of Digital Media in the School of Digital Arts (SODA) at Manchester Metropolitan University, UK. Founding a range of collectives such as the KIT Collaboration, Battery Operated and AUDINT, his cross-disciplinary methodology is the driver of installations, mobile apps, books, immersive experiences, vinyl recordings, performances, and multi-sensory environments. Much of Heys’ recent funded work focuses on the sonic, haptic and interactive elements of the immersive experience, an area he has been exploring and advancing for over 30 years through industry-based projects, gallery exhibitions and festivals. He also works on the on/off boarding of immersive experiences and the multimodal approach to narrative construction in installations that utilise advanced digital technologies XR, AI and robotics.

Heys has produced over 100 solo and 100 group exhibitions for museums, galleries and festivals around the world. He has produced multi-sensory immersive installations for venues such as Tate Britain (London), The Academy of Art (Berlin), The Phi Centre (Montreal) Art in General (New York) and Zorlu Performing Arts Centre (Istanbul), Photographers Gallery (London) and Arte Alameda (Mexico City). Heys has also produced performative installations for many festivals including Transmediale (Berlin), Mutek (Montreal), Multimedia Art Asia Pacific (Brisbane) and Unsound (Krakow).

Heys has written five books that range from expanded graphic novels to academic research texts. Recently he wrote AUDINT’s Ghostcode (Multimodal), which is accompanied by a double vinyl soundtrack and edited AUDINT’s Unsound/Undead (Urbanomic). He is co-author of the upcoming book Listening In: How Audio Surveillance became Artificial Intelligence (Bloomsbury, 2026) and is working on a new book, Phantom Channels, for MIT Press.