The work is an embodiment of the answers Google’s large language model Gemini gave when asked to describe itself.

Louis Jebb: You have a broadly based practice as an artist, working across video installation, sculpture, photography, and two recent London-based premieres. One of the through lines between the two pieces is the choreographer Wayne McGregor, who you have collaborated with for eight years, most recently on the sculpture A Body for AI. He also introduced you to Google, in 2019; a connection which has led to his year’s premiere of your AI video piece Self-Portrait.

Ben Cullen Williams: My practice is rooted in photography, and writing is the way it conceptually develops into larger-scale, more involved, works. I’ve been exploring video work and, in the last couple of years, combining it with structure, sound, and light to create layered systemic installations mixed with performance in a gallery context. I’ve also worked in a similar vein with Wayne McGregor since 2017, but contributing to his works on stage. We’ve made a number of pieces together and we have a collaborative work in his new exhibition: A Body for AI, a six-metre-by-three-metre folding kinetic sculpture where video is projected onto the piece. The sculpture is located in a soundscape created by Invisible Mountain, which uses Bronze AI to turn real sounds into generative sonic textures. It is a smaller version of Harnasie, a work that was suspended above an orchestra for performances of A Body for Harnasie in 2024.

At the core of my work, I am interested in how natural landscapes and our corporeal worlds are altered by human technological intervention and the lenses through which we view those things.

In the case of A Body For Harnasie it was the relationship between body and landscape set within the Tatra Mountains in Poland, in a reimagining of a Polish ballet [Karol Szymanowski’s score Harnasie].

A Body for AI is a lone kinetic dancer or a technological fragment that has different types of live-action footage projected onto it — some motion capture, some AI, some digitally filmed; exploring different forms of image-making and processes of alteration. Sometimes the sculpture goes flat; sometimes it folds; sometimes it folds and rotates to move up and down. It has video coming in and out focus, an archive of imagery fading on and off the piece as it moves.

LJ: When did you start working with AI?

BCW: As an eight-year-old I did a project on Scott of the Antarctic, and had seen the photographic series by Herbert Ponting, the photographer on Captain Scott’s expedition. In 2016, I was invited by the explorer Robert Swan to go with him to Antarctica, where I took a black-and-white photographic series, very much with Herbert Ponting’s images in mind, as a contemporary reimaging of these shrinking landscapes. When I got back to the UK I found myself looking, tangentially, at images from the early 20th century where people painted colors onto black-and-white images: the recolorization of the past. Because the Antarctic was changing so fast, my images already felt “of the past” and I started working with a model that recolored the black-and-white pictures using data from images found online. That was my first experiment with photography and AI.

The resulting images were slightly uncanny as the colors weren’t quite right, I enjoyed this slightly unsettling emotional pull.

LJ: And who were you working with at that point?

BCW: Just by myself. But then I wanted to be more ambitious with it. I had met Google Arts and Culture through McGregor. A couple of engineers from there helped me with a video work, Cold Flux (2019), which was a form of rebuilding, creating AI landscapes of Antarctica.

We used and enhanced an algorithm which could create video from video and applied it to video footage of the last of the Larson B ice shelf, from my trip to Antarctica.

I was interested in trying to “rebuild” the ice shelf, using that which is, to some extent, destroying it: the increased use of modern technologies. The algorithm looked at video footage of the ice shelf and generated an infinite number of unique polar landscapes as a response. There was this fascinating relationship between knowledge and non-knowledge. As the algorithm learned, the images crystallized and became clearer and more legible.

As a result of that project I met another AI researcher from Google, Jason Baldridge. About three years ago he asked me, “Is there anything that’s interesting to you about AI text-to-image models?” At the time, I had read an article about the internet being formed of these large industrial systems of underwater sea cables, landing stations, and distribution networks — technology that still stems from the industrial revolution: factories, steelworks, milling, blast furnaces — making all of this infrastructure to transport signals and store information.

We got the AI to describe itself visually, instead of my going out and researching it. I became fascinated by the concept of a self-portrait by an AI.

How would it see itself? This was three years ago, working with an early text-to-image model, Google’s Parti. But I couldn’t get access to the models we needed. Three years later, Jason contacted me, saying he had moved to Google DeepMind, developing image and video models. We revived the old project, which has become Self-Portrait.

LJ: How has your background in photography informed Self-Portrait?

BCW: A lot of my work stems from being in the darkroom working with 35mm film, medium-format, large-format photography, and moving image. I use a lot of 16mm and 8mm film and am interested in the alchemy that happens when light hits the film, in the camera and in the darkroom afterwards.

I'm interested in what you can do to negatives, putting them through different types of chemical baths, including chlorine. This fed into Chlorine (2023), a film I shot across Spain [that] documents human manipulation of water and how our interventions have altered the Spanish landscape. From reservoirs, waterparks, and abandoned leisure complexes to mines containing the salts that end up as chlorine in swimming-pool water.

I was interested in seeing if we could use AI as another form of image disruption, another step in this image alteration. Earlier this year, we made five bespoke image models, trained on my photographs. One model might have been trained on blurry black-and-white photographs taken on a 35mm Canon camera; another on negatives I had treated with chemicals to the point of destruction. The aim was to create models that contained a digitized version or myself rather than a fetishized AI aesthetic or a seductive CGI gloss.

Then I asked Google’s large language model, Gemini, to reveal itself: “What do you know about yourself?”

It turns out it knows a lot about itself, from where the cobalt is mined in the creation of the chips that end up in a data center in, say, Oregon. Gemini knows that the wider generative AI infrastructure is vast: from open-source information of where the new data centers are being opened up, how many people work in them, [and] what sort of backgrounds they are from.

I found it fascinating, turning the lens back on AI itself.

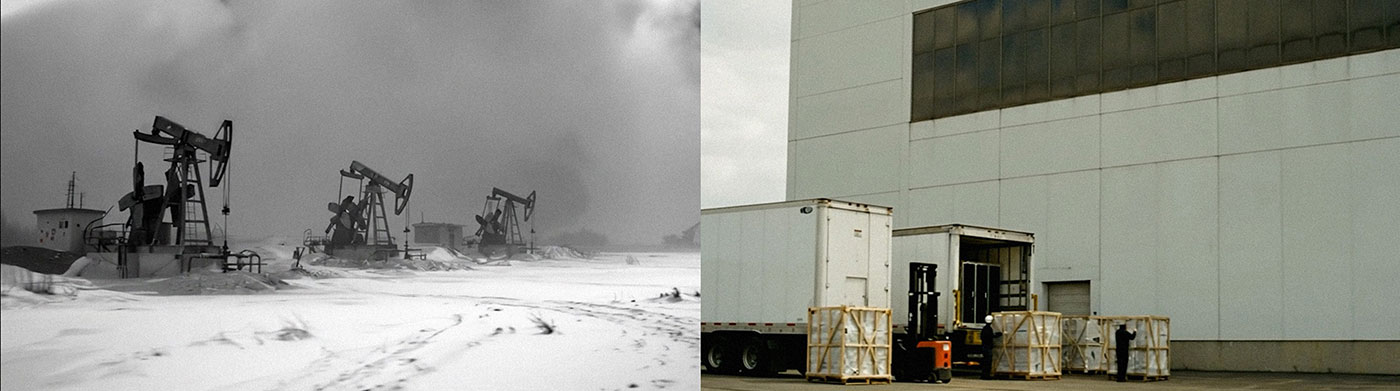

And then, using Google Imagen, I fed the text outputs into the algorithms we had made to create a series of image sets: an archive of imagery of the larger AI system, with cobalt mines in Kazakhstan, underwater sea cables, satellite dishes on the edge of a rainforest. And then those images were brought into a video model, Google’s Flow, to animate them, before I edited those clips into a film.

I tried to strike quite a neutral tone in the film. I wanted it to have a criticality, but I didn’t want it to fall into a stereotypical dystopian world. I also wanted to have positive notes, points of optimism, and beauty. Did you know that AI can be used to help regenerate coral reefs? I tried to allow the viewer to sit within the technological infrastructure rather than trying to be too polemical about it. The crux of the work is a question. The subject is AI, and the medium is AI, but much of the work is about authorship, and the relationship between the machine and the artist. And where is that line between the two?

Is it a self-portrait of the AI? Is it a portrait of myself?

The work is a vehicle to ask some of these wider questions about the relationship of the artist and technological processes within the space of contemporary art.

LJ: Can you talk to the wide, letterbox-shaped, aspect ratio of the video, where you sometimes pair images horizontally and sometimes show a single frame?

BCW: I wanted it to have references to CinemaScope and wide-format medium, to be cinematic, and the antithesis of how a lot of content is consumed today — the portrait format on your phone. I also wanted the work to have an emotional draw, a sense and feeling of being present in a landscape.

I have always been preoccupied with landscapes. JMW Turner is one of the big inspirations in my work. Last year, I climbed to the top of Mount Etna when it was erupting. But how I interpret and what I define as a landscape has changed. For example, I now see the corporal body (our flesh and blood) as a part of our natural landscapes, equally susceptible to human alteration. The wide format allows that split screen — two alternate realities of the same thing, side by side, rather than one fixed reality at any one time.

LJ: Can you talk about the music and sound effects in Self-Portrait?

BCW: The sound effects — of footsteps or of water — are generated by the AI model: like an AI “Foley”. For the score, I worked with two composers I have collaborated with before: Gaika Tavares and Harrison Cargill. I showed them the work and asked if they could both bring some ideas to the table. I wanted two people to feed in, for a sense of duality in one singular thing. They both created sound archives from which we took musical devices. I worked with Harrison to arrange it, stripping it back to find sounds — either sad or optimistic — to put you in a limbo space, where you’re drifting around, floating in the ether, untethered. I wanted it to feel very real, with cello strings, say. I did not want it to feel “digital”.

Just as I wanted the images to feel human. I wanted the sound, created with digital synthesizers, to feel human as well.

LJ: Some of the most interesting work done with photography and AI in the last two years has involved ambiguity. Artists such as David Sheldrick and Bennett Miller talk of avoiding being too prescriptive in their prompting in order to allow their AI models to hallucinate in an interesting way. Does that ring true to you?

BCW: Certainly. There’s a performance I worked on with Wayne McGregor in 2019 that stemmed from Living Archive, an AI tool for choreography he developed with Google Arts and Culture. It was trained on records of his previous choreography; it could make choreographic phrases collaboratively with a dancer. I then worked with that AI to make a 15-minute piece of choreography, which we output visually in a number of different ways.

During the editing I tried to not privilege my human lens; avoided cutting out things that the viewer might see as ugly or strange.

The tricky thing now is that AI models are getting better and better. So there’s less room for that blurriness or strangeness to happen, so we need to push these models off-grid to make things aesthetically uncertain and intangible, to create more space to feel.

I was aiming to do this with the fine-tuning of the Google DeepMind models, trying to work with them to bring some of the unfamiliarity back into them and make them feel less polished, more uncertain. I’m interested in the imperfection of things [and] in the space and transitional time between two events, not the event itself. I never really see any work as finished.

LJ: And what about working with Wayne McGregor; how did that come about?

BCW: I was perhaps three or four years out of the Royal College of Art, in London. I was working on large-scale sculptural installations and was fascinated by how the human body could affect those landscapes. You have a space, then a space with a body in it. What is the relationship between the two and how does each one shift?

Wayne and I started speaking when he was developing his work Autobiography, a contemporary dance piece that premiered at Sadler’s Wells, London, in 2017. My studio at the time was just across the canal from his in Hackney Wick, east London. He invited me to design the scenography and projections.

We developed a kinetic ceiling that moved up and down, that trapped space, with arrays of lights that slid between it.

At the very back of the stage, there were three projectors that shone out into the audience. The dance was based on his DNA, his own bodily archive, with that archive of information being projected, conceptually, out into the audience. It was an inhabited landscape of sorts, a system that needed to be brought to life by humans — moving from the desolate and empty to the full and vibrant.

He’s such an inspiring figure and a privilege to work with. I remember when I first sat down with him, he got his notebook out and started writing. And I thought “What am I saying that could warrant Wayne writing anything down at all?” I was nervous to say the least.

There are so many cross-interests in what Wayne explores in his work and in what interests me. And we’ve collaborated on a number of projects together since.

LJ: You work in hybrid ways at the intersection of different practices. But how do you situate your practice?

BCW: I’m particularly drawn to work that operates at different registers, challenging what art is in itself and what an artist can be or do. It’s liberating rather than constraining. I didn’t become an artist to be anchored.

Recently, I have been included in more digital art conversations and spaces. This is new to me, even though I have been using digital tools for some time in a number of my projects. People often talk and present digital art as set aside. It has perhaps historically been marginalized from much of the discourse of contemporary art, and perhaps it needed to be given its own voice and space.

More recently, crypto and NFTs have engaged an audience that previously might not have engaged with contemporary art at all. These conversations, these separate worlds, need bridges and connecting figures.

A lot of artists who define themselves as painters might be interested primarily in process and in the application of paint to canvas, with the subject a secondary consideration. For other artists, like me, the subject is the preoccupation, the core, the middle. How that manifests: as a film, an installation, a sculpture, a drawing, radiates out from the idea, and the process follows.

With Self-Portrait, using analog or digital film capture would have been at odds with the concept, as the work grapples with AI looking at itself, in a continual loop. If I was filming it, I would be illustrating the idea of AI rather than making a manifestation of it. Self-Portrait is not an illustration of an idea. It is the idea, the medium, the concept, the work, and the message collapsed into one.

Ben Cullen Williams is a London based artist, whose practice moves between mediums and modes of presentation. In his work, Williams explores the spectacle of human made alterations of our natural landscapes and corporeal world through various lenses and technological devices. He has collaborated with Wayne McGregor, Polar Explorer Robert Swan and Google Arts and Culture and MIT Media Lab amongst others. His work has been shown internationally in a range of spaces, galleries and environments. Exhibitions, performances and screenings include Musée d’arts de Nantes, CAFA Art Museum Beijing, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion Los Angeles, Somerset House London, Shinjuku Vision Tokyo and the Venice Biennale.

Louis Jebb is Managing Editor at Right Click Save.