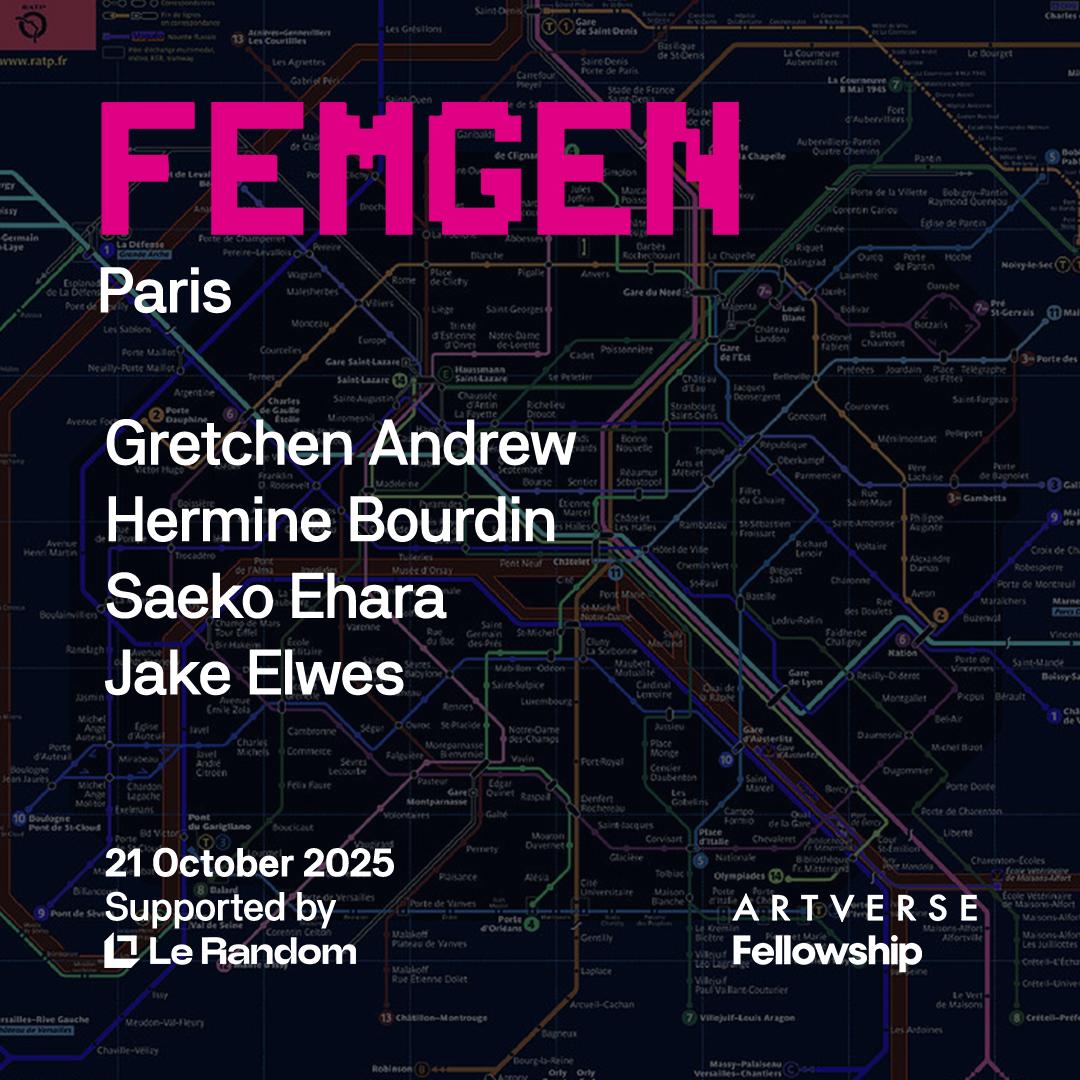

Sign up to attend FEMGEN Paris at Artverse and collect works at Fellowship.

Alex Estorick and Micol Apruzzese: We feel very lucky to have you all as part of an expanding FEMGEN community. These annual events and exhibitions are a vital way of preserving the conversation around inclusivity at a time when the digital art world has taken on some of the exclusionary tendencies of the legacy art world. How does it feel to participate in FEMGEN and what can you share of your own experiences of breaking barriers to participation?

Gretchen Andrew: The priority should be an openness to ideas, to difference, to education, and access to tools and information. But the trajectory is so predictable. When digital art felt like an outside, it utilized that outsider persona to feel important, and then as soon as some artists started to cross the divide and get fancy exhibitions, there was a clamor for validity.

My work has long been about the outward desire to be part of the legacy artworld — my “Vision Board” series was literally about that — because I see it as a place of aspiration and tradition. Although it is highly imperfect, it is also full of experts who have devoted their lives to pursuits that I find compelling, while technology almost always ends up as a tool of conformity and control.

My Facetune Portraits show how diverse faces and bodies are compressed into a single form. There is a democratization in these tools in that anyone can use them and they don’t require special skills, yet they are flooding our media and setting expectations in really damaging ways.

Hermine Bourdin: It feels really special to be part of FEMGEN. There is an honesty and generosity in this community — a living conversation about art, identity, and technology that keeps evolving.

As a sculptress, I come from a highly physical and material practice, so using digital tools can sometimes feel like stepping into a space that was not made for me. Over time I have learned to treat these tools like any other media, shaping them, questioning them, and making them mine. FEMGEN celebrates that kind of freedom. It is about reclaiming technology as a creative space rather than a technical one, and that is why I am so happy to be part of it.

Saeko Ehara: I feel truly honored and grateful to be a part of FEMGEN and to have the opportunity to meet and connect in person with curators and other artists. I am normally based in Tokyo, and although the internet has made it easier for people around the world to connect online, physical distance remains a significant barrier to participation for many artists in Asia.

Currently, I am staying in Switzerland for an artist-in-residence program, residency.CH, and being physically present here has made me deeply aware of the differences in culture, access to knowledge, and the ways in which artist networks function. That is why I believe it is so meaningful for Asian artists to come to Europe, to engage in dialogue with local curators and artists, and to be inspired by these encounters.

FEMGEN provides a valuable platform that bridges cultural and geographical distances, fostering new forms of understanding and empathy.

Jake Elwes: I’m delighted to participate in FEMGEN as a queer and non-binary media artist and I’m really excited to exhibit alongside so many fantastic fem-artists.

One of my proudest moments was collaborating with and then platforming a diverse group of 21 London-based, trans and queer drag performers at the V&A. They featured in my video installation, The Zizi Show (2023) which was installed in the museum’s new Photography Centre, and at a Friday Late event where I was able to invite in eight performers to take over the vast Raphael Court. It was a moving moment for a lot of the performers — some teared up, saying they never thought they’d see themselves and so many of their friends in such a renowned and imposing institution.

AE & MA: This year’s physical event and installation is being hosted at Artverse in Paris, with a sale of works online at Fellowship. How do you approach the fluid nature of digital art, where works can be experienced through multiple platforms and formats, and across physical and digital domains?

HB: For me, the fluidity between digital and physical realms is essential, it’s where the work truly comes alive. With my new work Universal Venus, the process begins in the digital space, using databases and AI to generate forms, but it always returns to sculpture.

A digital Venus might seem distant and dreamlike, but when it becomes stoneware, it gains presence, gravity, and touch. Exhibiting the work in both environments allows me to explore how meaning and perception shift across these spaces.

In many ways, that fluid transition reflects our own condition today — existing simultaneously in physical and digital worlds, constantly translating ourselves between the two.

SE: I have presented my works in various formats, including NFTs, audiovisual and screen-based pieces, public signage, immersive installations, and physical prints. Because digital art can take on so many different forms, I value the flexibility to adapt its presentation — whether online or offline — so that it feels most natural to each specific environment or platform. To me, this approach is similar to how people in Japan change what they wear or eat according to the seasons. I find beauty in the way an artwork can transform in harmony with its surroundings.

JE: I tend to start with the concept and then try to work out the best way to display the work to communicate and engage with an audience.

While my projects often start in the digital realm I tend to spend a while thinking about the physical space a work might inhabit in a gallery or museum context to consider the ways in which it will be experienced.

I’m excited to take further how digital and online audiences can experience and engage with my work through collaborations such as this one with Fellowship.

GA: I believe that part of the job of the artist today is to find our audience. It’s not our job to get someone to like our work, but it is our job to seek to connect with those who might. As artists, we have no more entitlement to anyone’s attention than any other form of media today. I always think about how Van Gogh’s Starry Night is a damn good painting IRL, but how it’s also wonderful on a mug or magnet because its power is not destroyed by a mutable context of presentation. To be an artist today is also to acknowledge that our images and works won’t be fixed to a single context of presentation, and to make works that are powerful enough to survive known and unknown modes of display.

AE & MA: Thanks to the support of Le Random, your works will be exhibited at Artverse alongside those of a number of pioneers, including Nancy Burson, Analivia Cordeiro, Copper Giloth, and Vera Molnar. How do you feel about being part of an intergenerational conversation, and does your work for this show respond to their works at all?

SE: It feels almost unreal to have my work exhibited alongside such pioneering artists. My new work Body Without Presence was inspired by Analivia Cordeiro’s computer-choreographed dances, in which the human body is symbolized and restructured through its relationship with technology. Following Cordeiro’s approach, I reinterpreted the symbolic gestures of traditional Japanese dances using generative practices. In this way, I sought to visualize the transformation and fluidity of these gestures in order to explore a new relationship between the body and technology.

JE: I’m delighted to be a part of a show that exposes an intergenerational conversation. I feel that my work follows on nicely from those of all the early media artists experimenting and hacking the technologies of their time.

There’s a poetry that emerges from the use of a system in a way it wasn’t intended to be used.

However, I feel that the conversation has shifted away from a techno-utopian vision into a more complicated relationship involving Big Tech and technologies being co-opted and not delivering what we originally believed they promised.

Analivia Cordeiro’s work with dancers as a way of navigating the digital plane and breaking technological patterns really appeals to me, and is something I’ve tried to explore in various ways throughout my projects. Nancy Burson’s critical exploration of identity also parallels my work around the queering of facial-recognition datasets away from normative representation.

GA: One reason I never felt grounded in the world of NFTs is that, early on, so much of it was ahistorical. But it is only in knowing what has come before that we can understand what is truly new. In that sense, my Facetune Portraits feel in dialogue with the work of these pioneers. Nancy Burson’s early facial composites used technology to explore identity and perception long before digital manipulation became ubiquitous, and I see my work as extending that inquiry into a world where these tools are now in everyone’s hands.

Analivia Cordeiro and Copper Giloth both used technology to examine the body as data, motion, and code, which resonates with the way my portraits show how digital systems standardize and reshape our physical selves. Vera Molnar’s algorithmic rigor and embrace of controlled randomness also echo through my process, which involves both automation and human intervention.

What connects us across generations is not the medium itself, but the act of using technology to reveal what it means to be human.

HB: It is a real honor to be shown alongside such pioneering artists — women who opened up paths by using technology to explore questions of identity and form. I have been working for a number of years on a database of Venus figurines from around the world to build an archive of goddesses. When I was invited to join FEMGEN, I immediately saw how this ongoing work could resonate with Nancy Burson’s Goddess (Mary, Quan Yin & Isis) (2007), which merged the faces of multiple spiritual figures to create a universal image of the sacred. I wanted to extend that idea by bringing together prehistoric Venuses from different cultures and imagining what a shared form might look like today. It feels like a dialogue across time and media, between ancient sculpture and the new languages of AI.

AE & MA: Either by accident or divine design, each of your works for the exhibition touches on the ways identity is mediated and manufactured in the age of the posthuman. What can you tell us about your own works for the show, which invite questions about the generation and erasure of bodies?

JE: DoomScroll is a visual representation of myself doomscrolling on my phone, which is abstracted through a slit-scan photographic technique that records the passage of time.

The resulting generative drawings convert time wasted on Instagram into something approaching the sublime.

My chipped nail varnish and hand gestures feature in the work but are constantly being washed away, like a musical score combining and morphing into the luminous screen of my phone.

HB: I have always been fascinated by the earliest representations of the human body, which represent enduring symbols of femininity. Created more than twenty thousand years ago, Palaeolithic Venus figurines are among the first artistic creations of humankind. They embody nature and the vital force of life itself. These Venuses are not portraits of individuals but universal symbols of life and continuity. With Universal Venus, I wanted to bring these primordial forms into dialogue with the present.

From my archive of Venus figurines, I trained an AI to imagine new Venuses — universal forms that merge and reinterpret the ancients, sometimes inventing new textures or imagined contexts of origin. These digital creations become speculative artifacts shaped by a combination of memory and imagination. But when sculpted in stone, I give substance to what was once data, translating it into tactile matter. This process reconnects the digital imagination with human gesture.

GA: One of the most surprising things about AI-driven beauty standards is that they show us crossing the uncanny valley from the other end — we are now intentionally modifying our faces and bodies both digitally and through plastic surgery in order that they appear artificial.

What I see in this global homogenization of beauty is not just a desire to be “pretty” but a desire to be like everyone else, to blend in and not stand out, thereby ending the cultural celebration of the individual.

SE: For Body Without Presence I trained an AI model using images of traditional Japanese dances such as Awa Odori, Yosakoi, and Bon Odori. The bodies were then generated and transformed through ComfyUI, a node-based AI tool. By further distorting these images in TouchDesigner, the dancers gradually dissolve into a single form, transforming into abstract presences devoid of individual meaning. For me, this dissolution evokes the state of identity in contemporary society. As we continually generate new versions of ourselves in digital spaces and on social media, we may be losing something essential about ourselves.

Sign up to attend FEMGEN Paris and collect works by Gretchen Andrew, Hermine Bourdin, Saeko Ehara, and Jake Elwes.

Gretchen Andrew uses search engines, social media, and AI systems as artistic media, hacking algorithmic visibility to explore power, desire, and gender. Her practice merges painting with digital culture, exposing the biases and mythologies embedded in technological platforms.

Hermine Bourdin’s sculptural practice extends into the digital realm through hybrid forms that challenge categories of body and object. By combining physical materiality with virtual environments, Bourdin questions the thresholds of femininity, sensuality, and digital embodiment.

Saeko Ehara creates immersive, generative installations that explore fluid identity and transformation. Her works often incorporate 3D modeling and AI-driven systems to evoke dreamlike, posthuman landscapes where gender and reality become mutable constructs.

Jake Elwes explores AI and queer identity through projects that subvert machine learning systems. Their works—including datasets populated with drag performers and non-normative expressions—destabilize the heteronormative assumptions encoded in algorithms, offering a playful yet critical vision of AI’s creative potential. Elwes is represented by Gazelli Art House.

Alex Estorick and Micol Apruzzese established FEMGEN in 2022 as an exhibition and series of curated conversations celebrating female-identifying and nonbinary artists working with generative systems. Born in the pursuit of a new art world that fosters diversity, openness, and greater access, FEMGEN is dedicated to cultivating a more inclusive ecosystem for artists. Now in its fourth edition, FEMGEN Paris pairs four emerging artists with pioneers from the Le Random collection, fostering intergenerational dialogue through code and curated conversation.