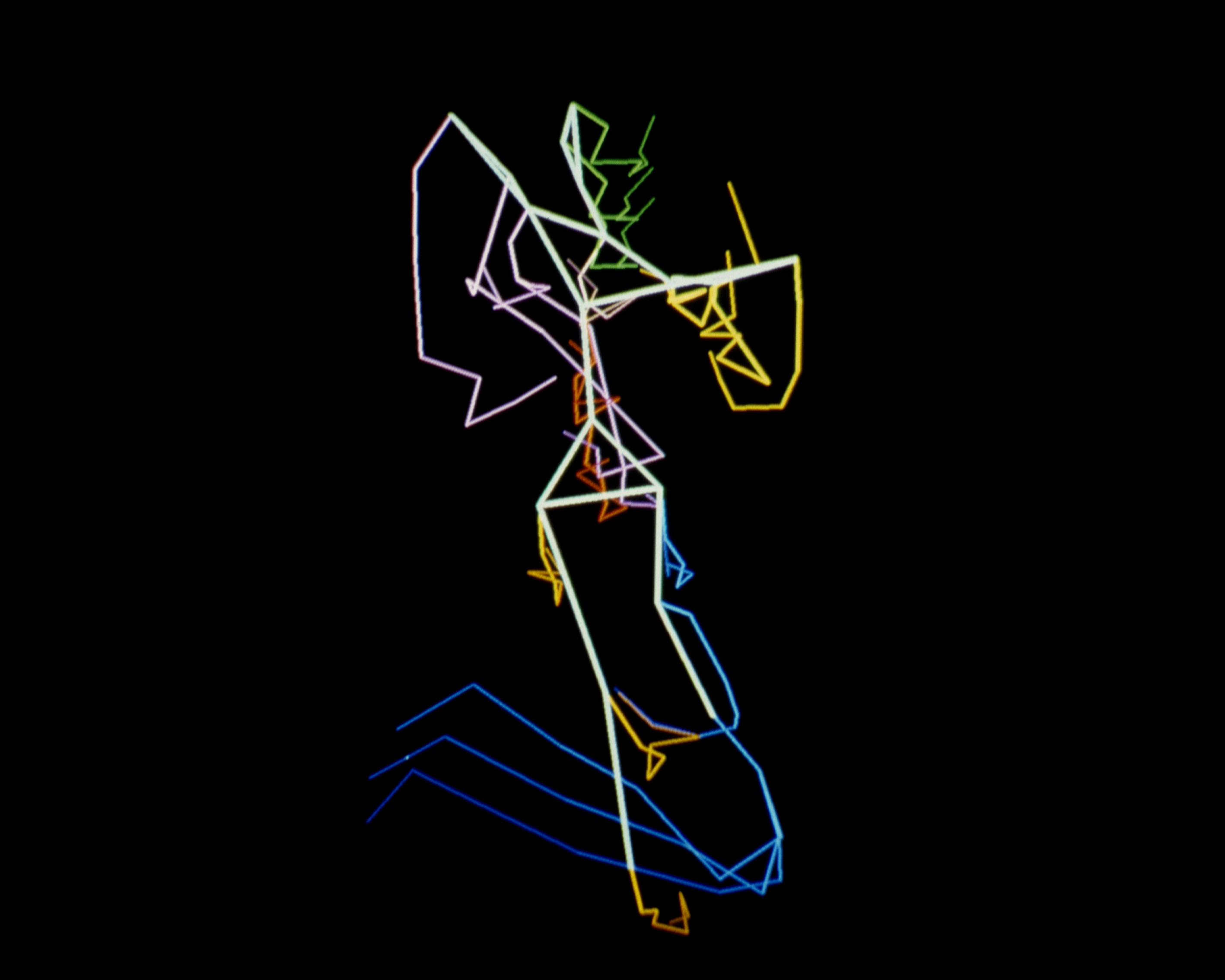

I began thinking about a friendship between technology and the body — never in opposition [but] something more like a feedback loop.

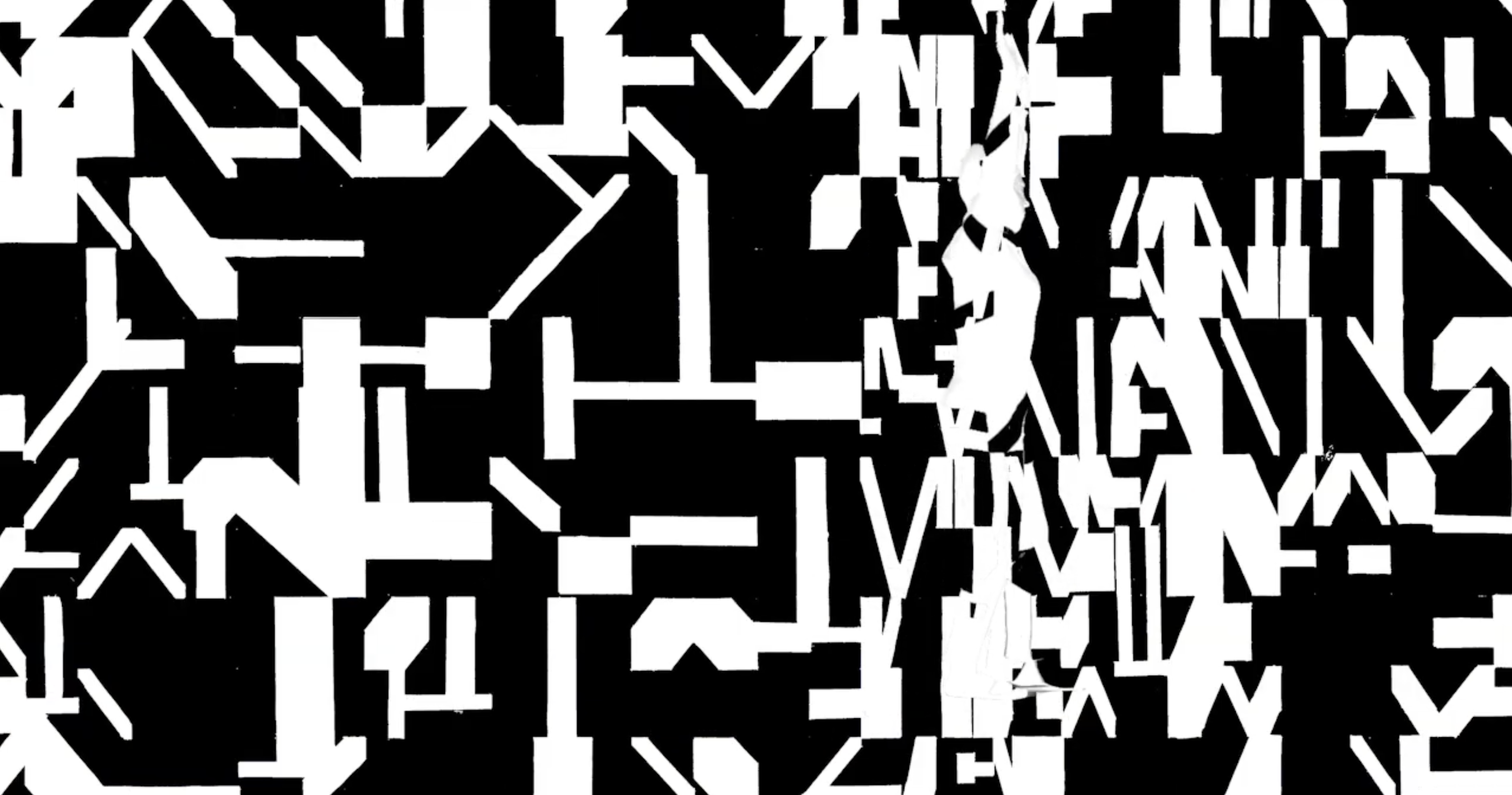

Improvisation and random choice both deal with the unpredictable. The difference is that improvisation is deeply organic and flows harmonically. Random choice is mainly chaotic and never organically constructed. They complement each other.

Improvisation, when combined with computer-generated instructions, never gets old — it can always evolve and be renewed.

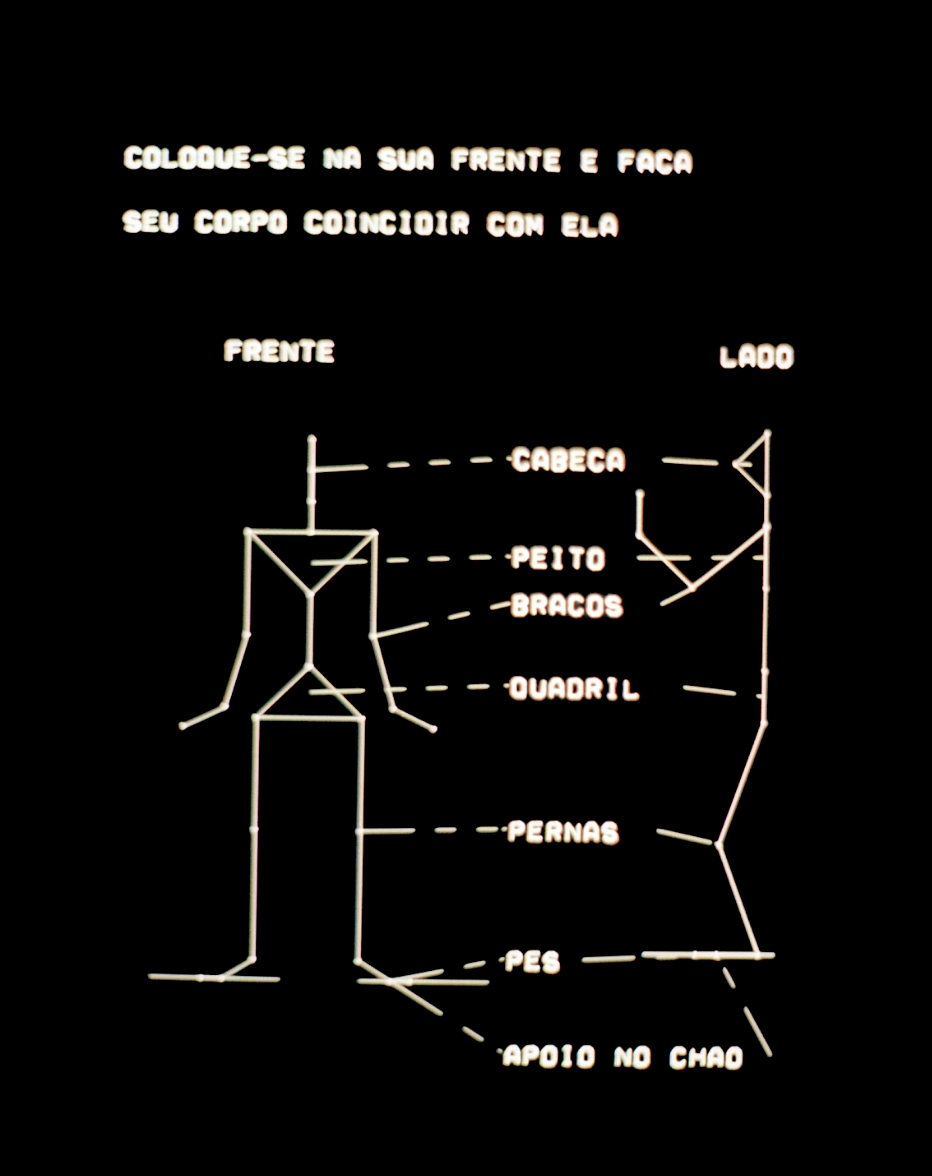

Analivia always cared about how to invite people to interact with technology in a way that felt invisible and didn’t interfere with their movements but rather encouraged people to move and create. Her priority has always been with moving people.

Because of the ways technology imposes how to communicate, a person — especially a girl — can close herself off, then her body closes: shoulders, then her back, then her neck. I’ve witnessed this whole transformation.

20 years ago, art and freedom were partners. Now, art is partnered with money, and there are people who say, “we don’t understand about art, that’s for the elite.”

The experience with the Kamayurá was amazing precisely because they have one single reality, one whole, one world.

.jpg)

I see body language as a vast, open space for development if one has the courage to be spontaneous, pure, and childlike in expression. That is how one finds the cracks through which individuality can still emerge.

That technology wasn’t designed for someone with a stroke, but we found a way to make it work for her. She found a way to move again, to feel alive again through the digital representation of her body.

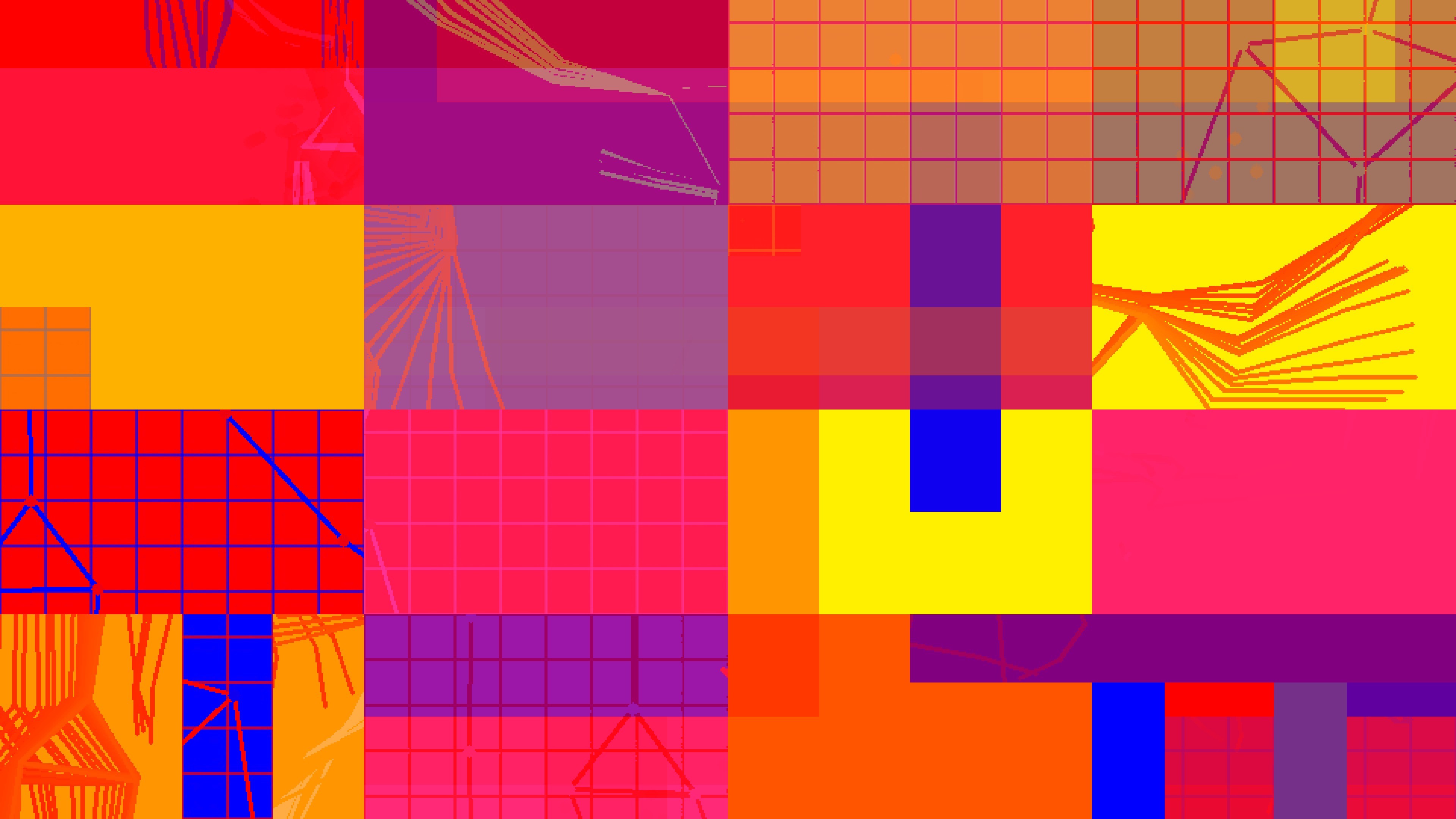

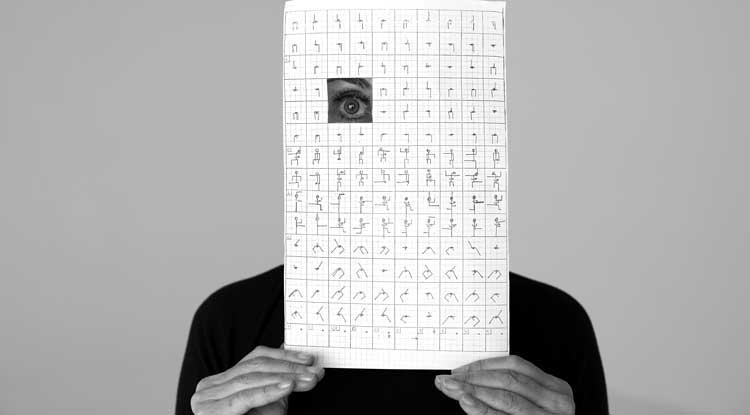

Analivia Cordeiro is a Brazilian dancer, choreographer, and artist who pioneered the use of computers and video in the design and performance of dance. Born in 1954, she is the daughter of concrete artist Waldemar Cordeiro. Since the 1970s, she has developed innovative methods for notating and capturing human movement using digital technologies. Her work M 3×3 (1973) is considered one of the first computer-generated choreographies. She continues to explore the intersection of technology and embodied experience through projects such as BodyWays, an app that allows users to capture and share their movements. Her work has been exhibited and performed globally and is included in collections such as MoMA, New York; V&A, London; and the Reina Sofia, Madrid.

Nilton Lobo is a programmer and engineer who has collaborated with Analivia Cordeiro for over forty years on various digital movement projects. He has been instrumental in developing the technical infrastructure for her artistic innovations, including early motion capture systems and the BodyWays application.

Alex Estorick is Editor-in-Chief at Right Click Save.

___

¹ P Bauman, “Analívia Cordeiro on Perpetual Motion” Le Random, July 17, 2024.

² E Shanken, “Coding Dance and Dancing Code: Analivia Cordeiro’s M 3×3” in S. Cody (ed.), Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952-1982, exh. cat., Los Angeles County Museum of Art and DelMonico Books, New York, 2023, 197.