Larva Labs will release Quine on Art Blocks Curated on October 9, 2025.

“When Erick offered us this,” Watkinson says, “we wanted to make sure that we did something that was fitting of that honor.” It also felt right, he says, “because Erick talks about Autoglyphs being the inspiration that sort of pushed the Art Blocks boat away from the shore.”

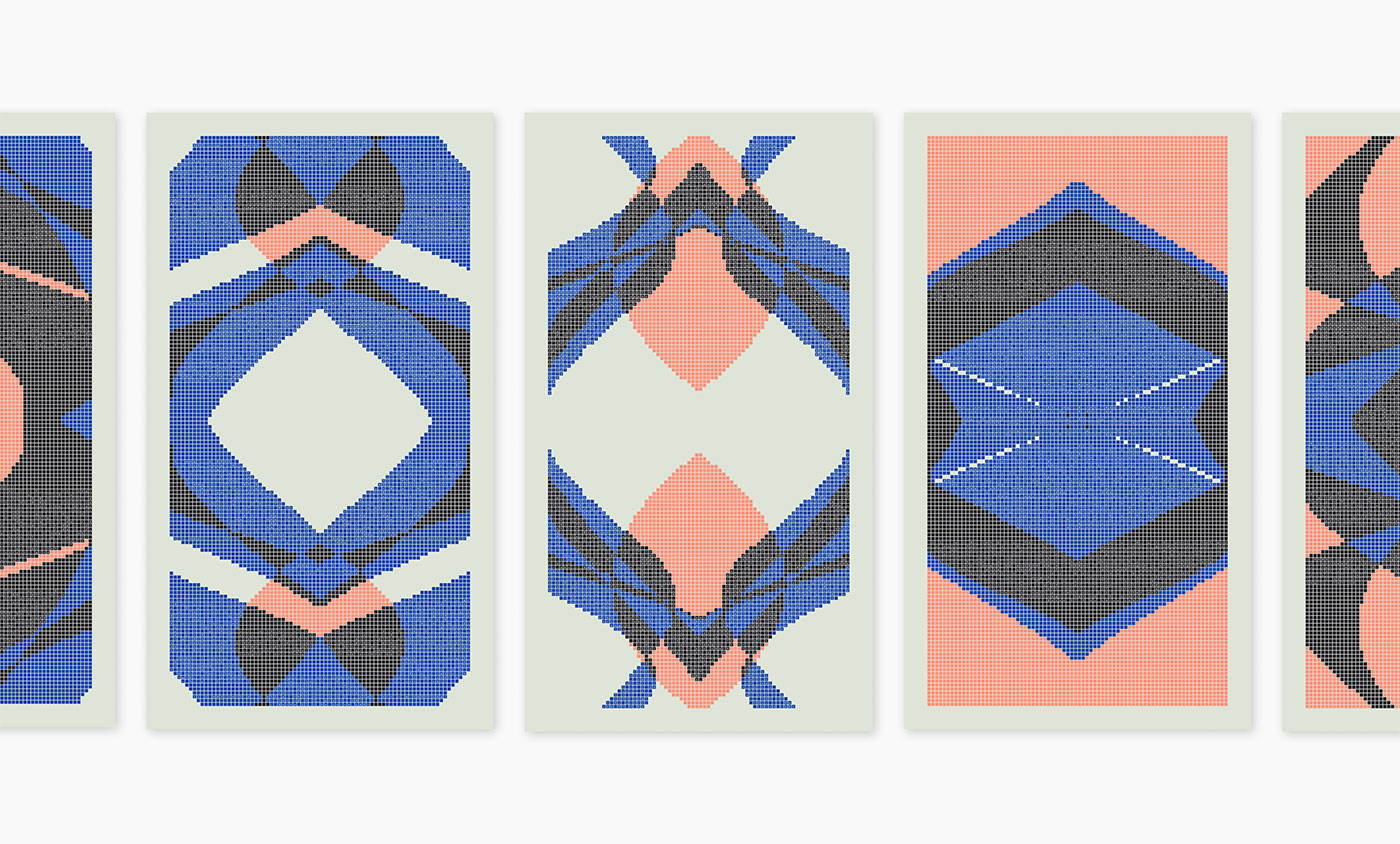

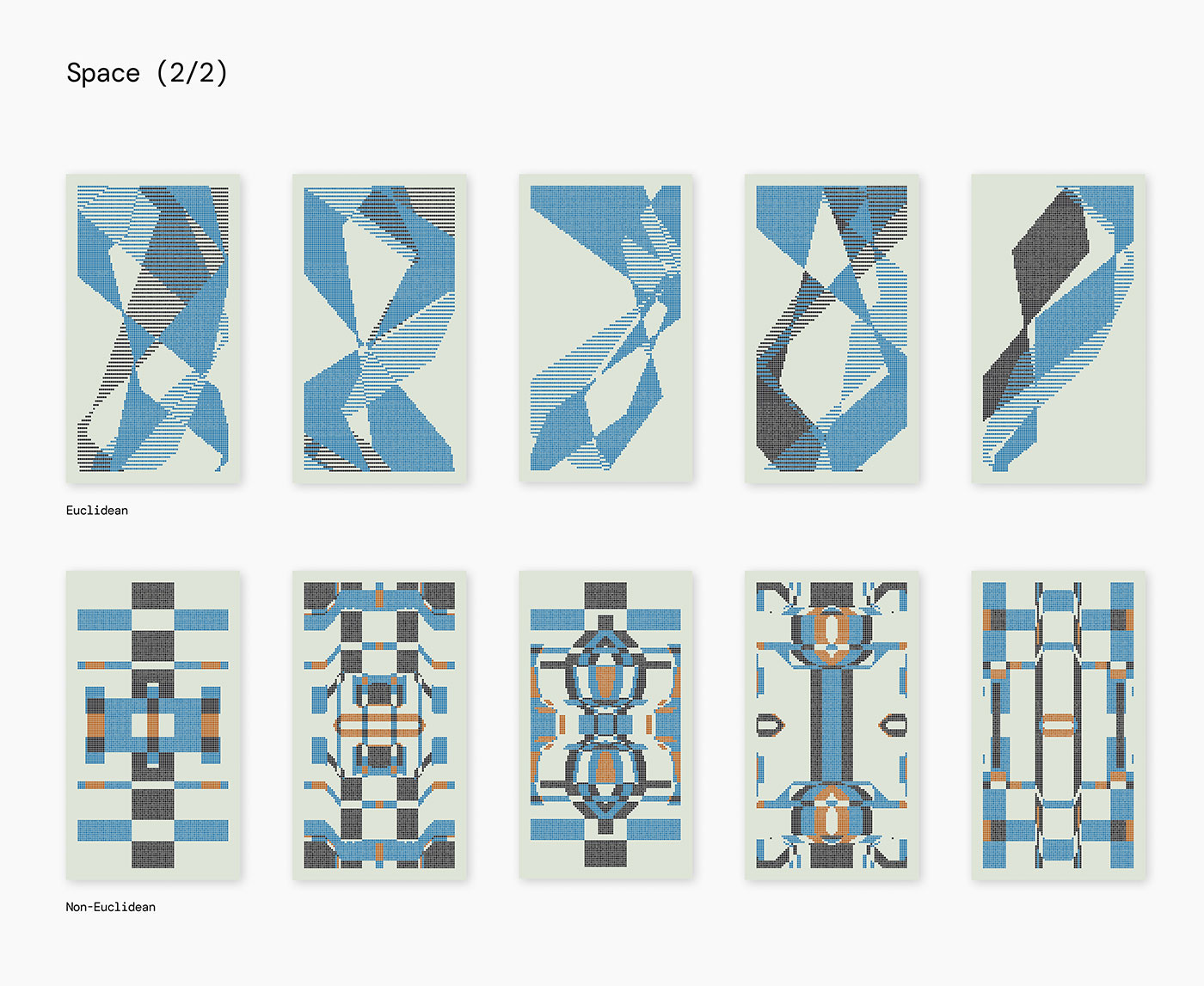

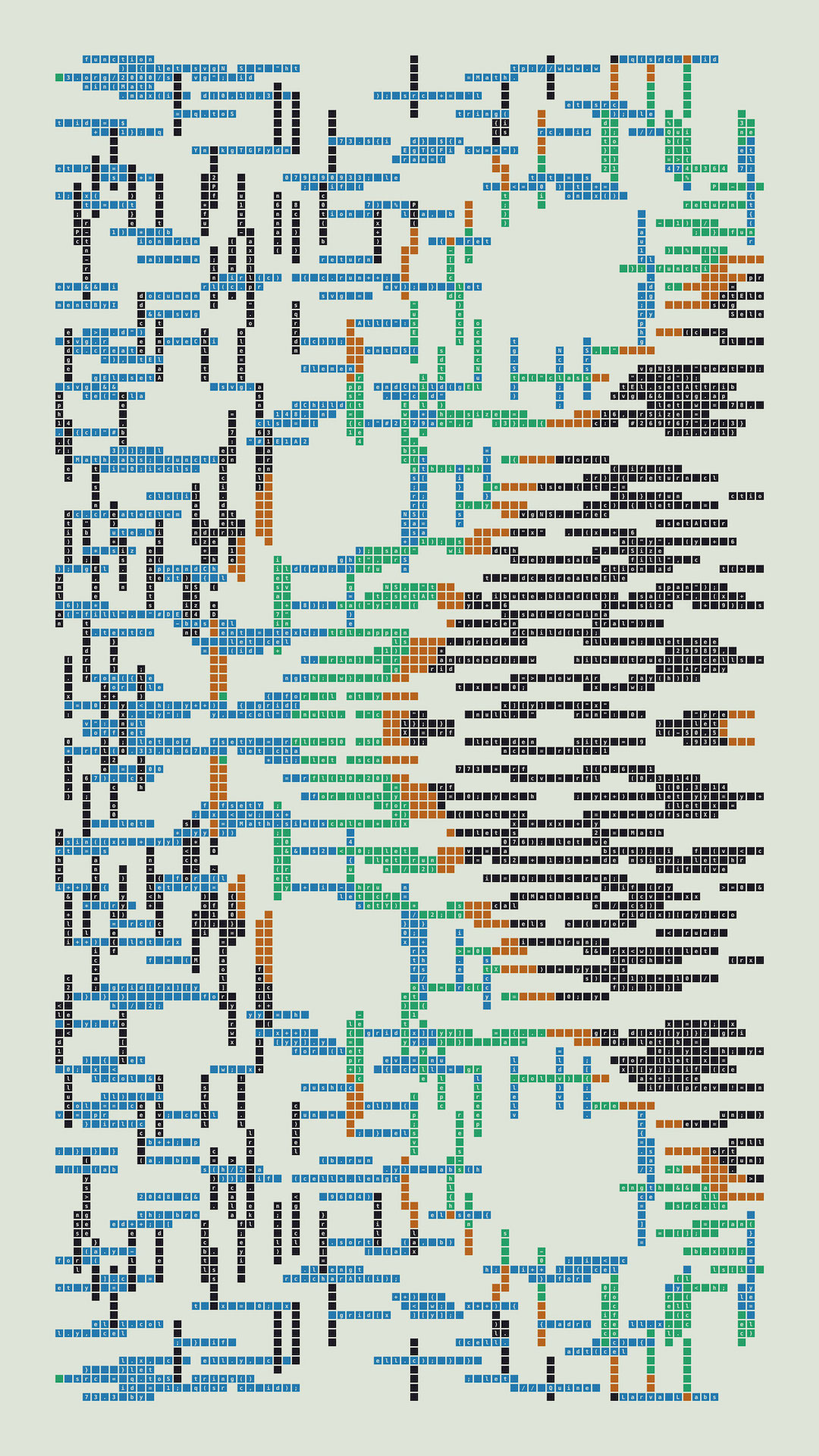

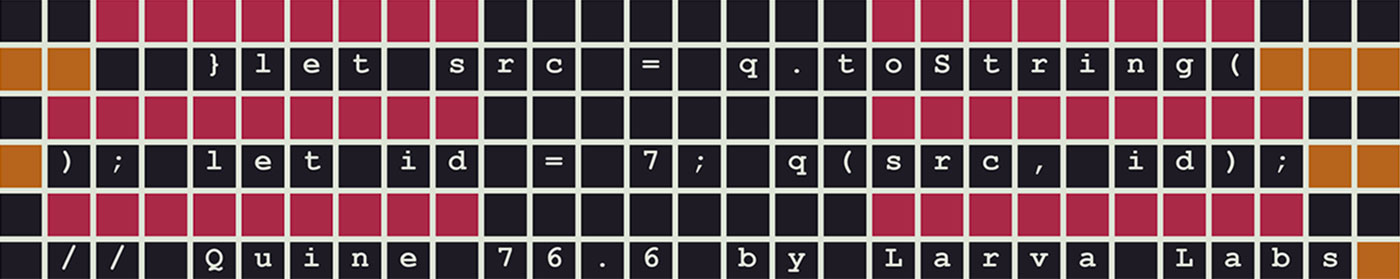

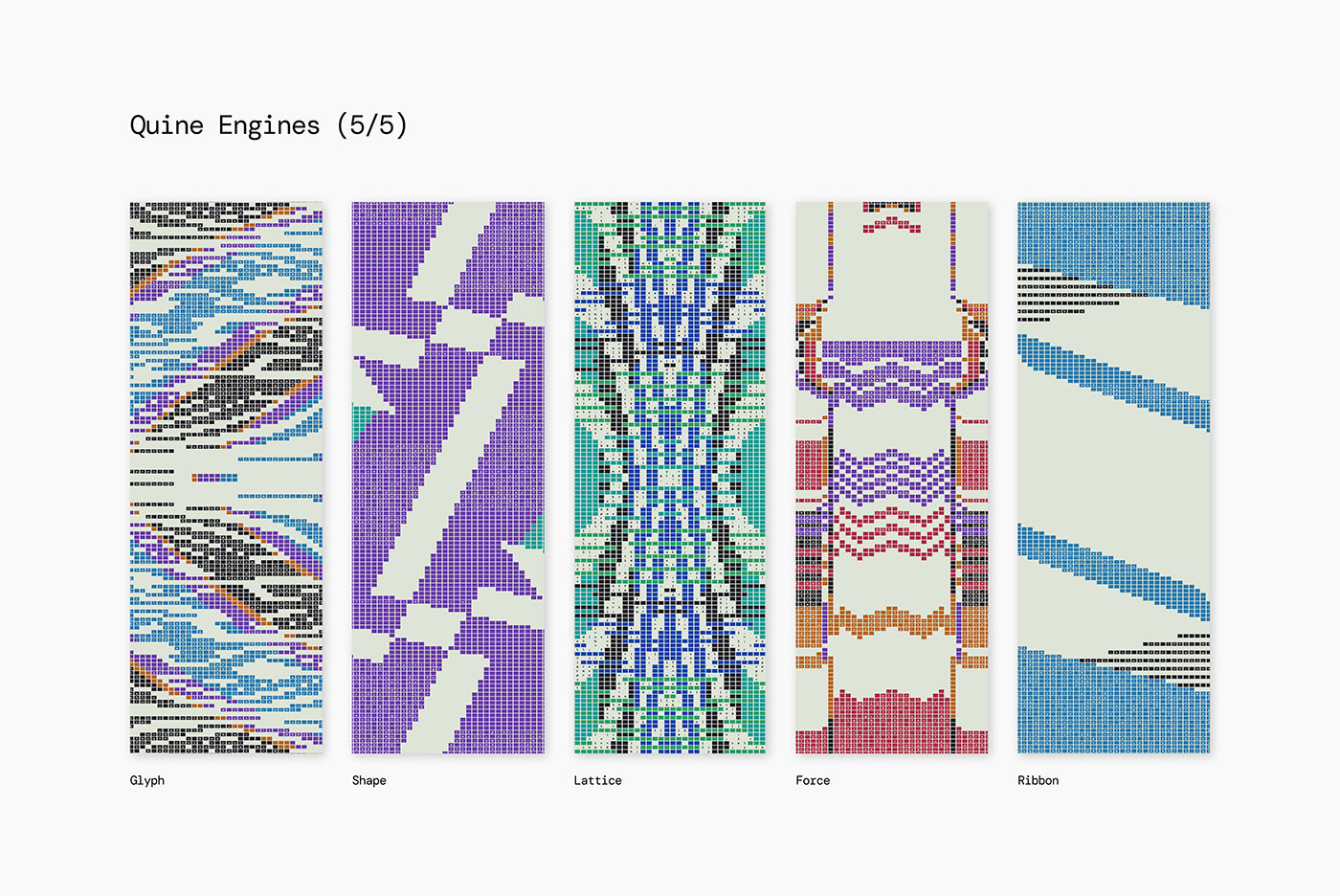

To honor code’s place in generative art, as well as the philosopher of self-referential paradoxes, Hall and Watkinson created Quine, where each unique artwork includes the program that generates it, extending Hofstadter’s computer science concept of a “quine” into visual art.

“What has been nice about the PostParam is that it gives you, the collector, some agency,” says Hall. “You choose as the collector what you think is the best output from your generator.”

“Autoglyphs is one of those things [where] the blockchain is part of the medium. It’s not just the algorithm that produces the output. So I feel like there’s lots to explore there still,” says Hall.

“That is what’s interesting and engaging about this Art Blocks model. You really are just standing behind the algorithm, not its outputs; and that’s a really cool aspect of it,” says Watkinson.

“I like to have that feeling of uncertainty. We certainly had it with Cryptopunks where it was like, ‘will anyone care about this?’ With Autoglyphs, [it was the] same kind of thing a little bit. That was at a time when there wasn’t a lot of interest really in crypto art. How are people going to react to this? How are they going to use it?

With thanks to Natalie Stone and Joana Kawahara Lino.

Larva Labs is John Watkinson and Matt Hall, long-time creative technologists and early innovators in blockchain art. In 2017 they created the CryptoPunks, one of the earliest examples of NFTs on the Ethereum blockchain. Along with a mechanism for digital ownership, the CryptoPunks contract also includes a fully decentralized zero-fee marketplace that has processed over $3.2 billion dollars worth of CryptoPunk transactions. Further work includes Autoglyphs (2019), the first fully on-chain generative artwork, and The Meebits (2021), generative 3D characters with an integrated zero-fee trading system. Yuga Labs acquired the intellectual property to CryptoPunks and The Meebits in 2022. Meebco acquired the IP to The Meebits from Yuga Labs in 2025, with Hall and Watkinson joining as strategic advisers in September 2025. NODE foundation acquired the IP to CryptoPunks in May 2025. Hall and Watkinson—with Erick Calderon, founder of Art Blocks, and Wylie Aronow, co-founder of Yuga Labs—are on the NODE advisory board.

Louis Jebb is Managing Editor at Right Click Save. He was previously Co-Editor and Managing Editor of The Art Newspaper and developed that title’s coverage of the intersection of art and technology, including artificial intelligence, blockchain art, and immersive experiences.

Larva Labs will release Quine on Art Blocks Curated on October 9, 2025.