.png)

I want everything in my life to be unique, and everything I do is about trying to make, mass produce, and automate individual items.

It takes up to 90 days to beat the game, and it’s really annoying. I can’t wait for people to tweet about how “this is stupid. I’m not coming back every single day for 90 days.” It’s really making my point of how hard it is to just show up every day.

If I go to get coffee in the morning, I get points for it. If I then take an Uber home, the driver gets what is essentially a quest notification on their head-up display, and completes the fetch quest to get me. I’m just some random NPC [non-player character] in his life. It’s like, “thank you for taking me back to the castle. Plus $6.”

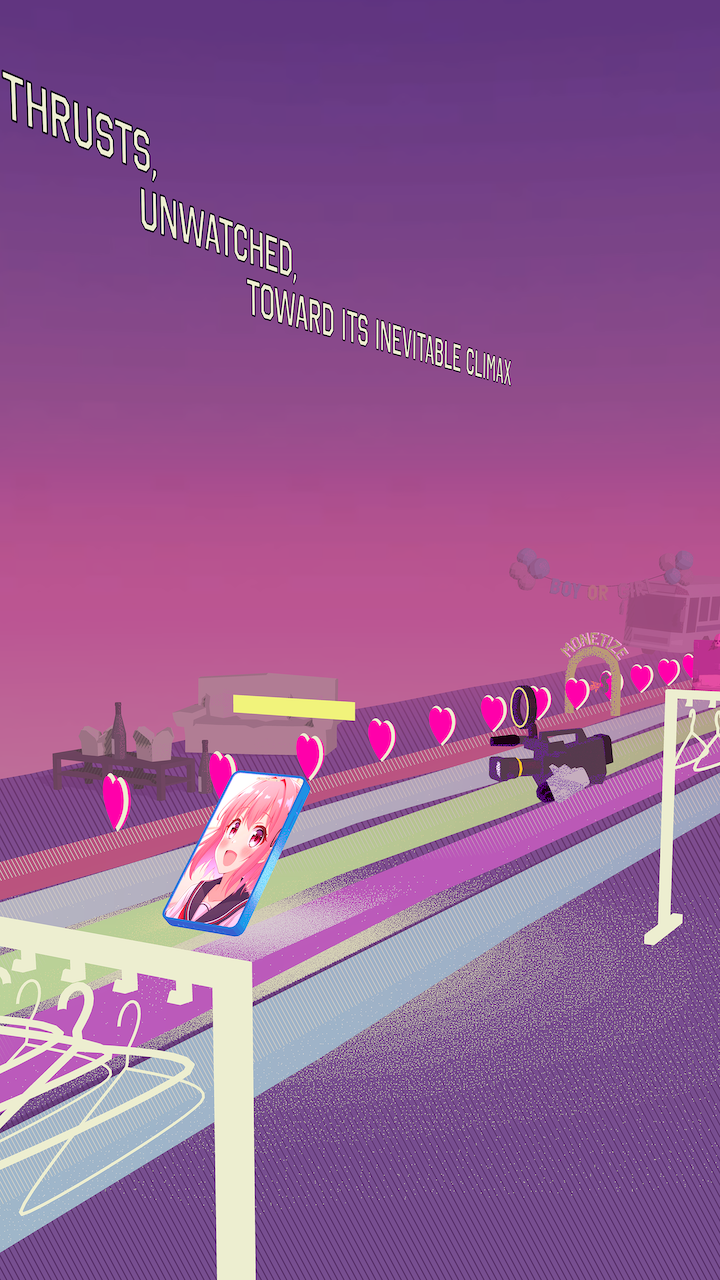

The trick is that I get the user to start off thinking they’re playing one game, and then I show them that they’re playing another game.

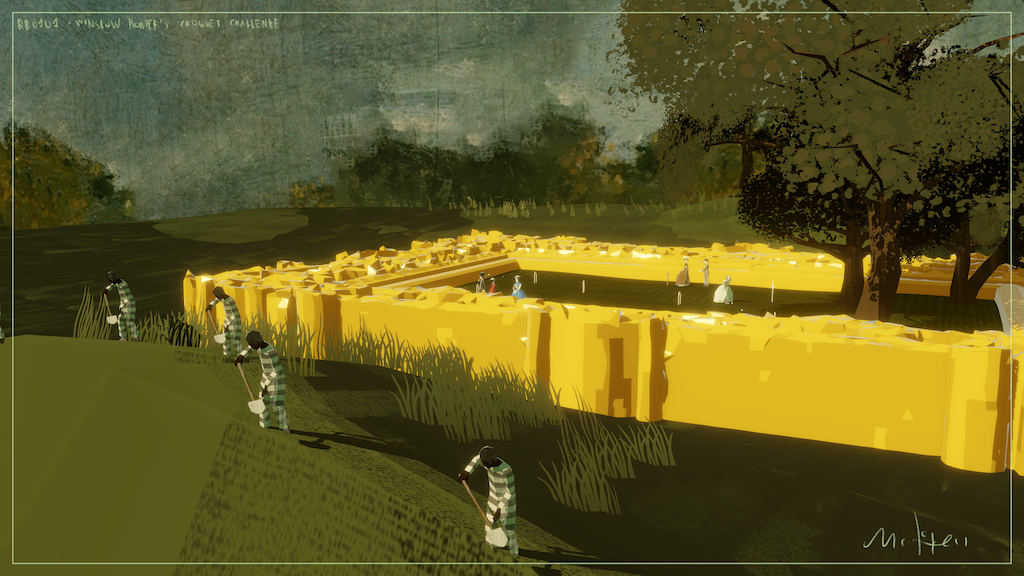

With Zantar, you start off playing a game, and then I take it away from you. Why do that? Because I believe that the way life works now, and the way it works being a consumer financial entity in the year 2025, is that society convinces us that we’re playing one game but it has this whole other second-order game that we’re all trapped in.

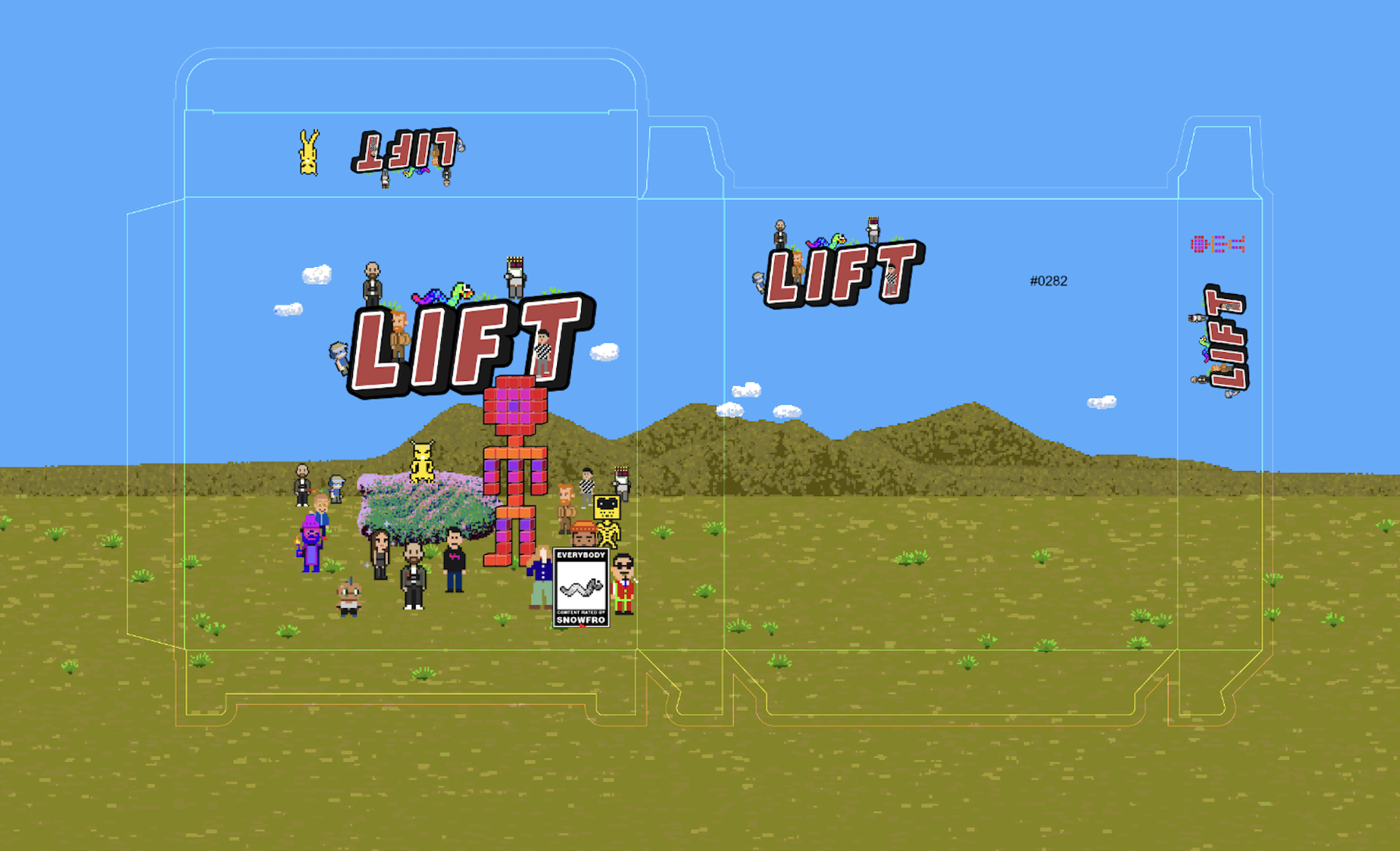

It’s really important to me to be able to give people the experience of a mass-produced video game with the same quality, box design, and insert, but yours is a unique, individualized object and there’s no other copy of it on the planet.

.png)

Most of the games that we play were created by hundreds of people over the course of years. If you’re just a lone artist, you have to pick and choose where your effort and where your complexity is going to be. You absolutely should not be trying to reinvent every single part of the wheel.

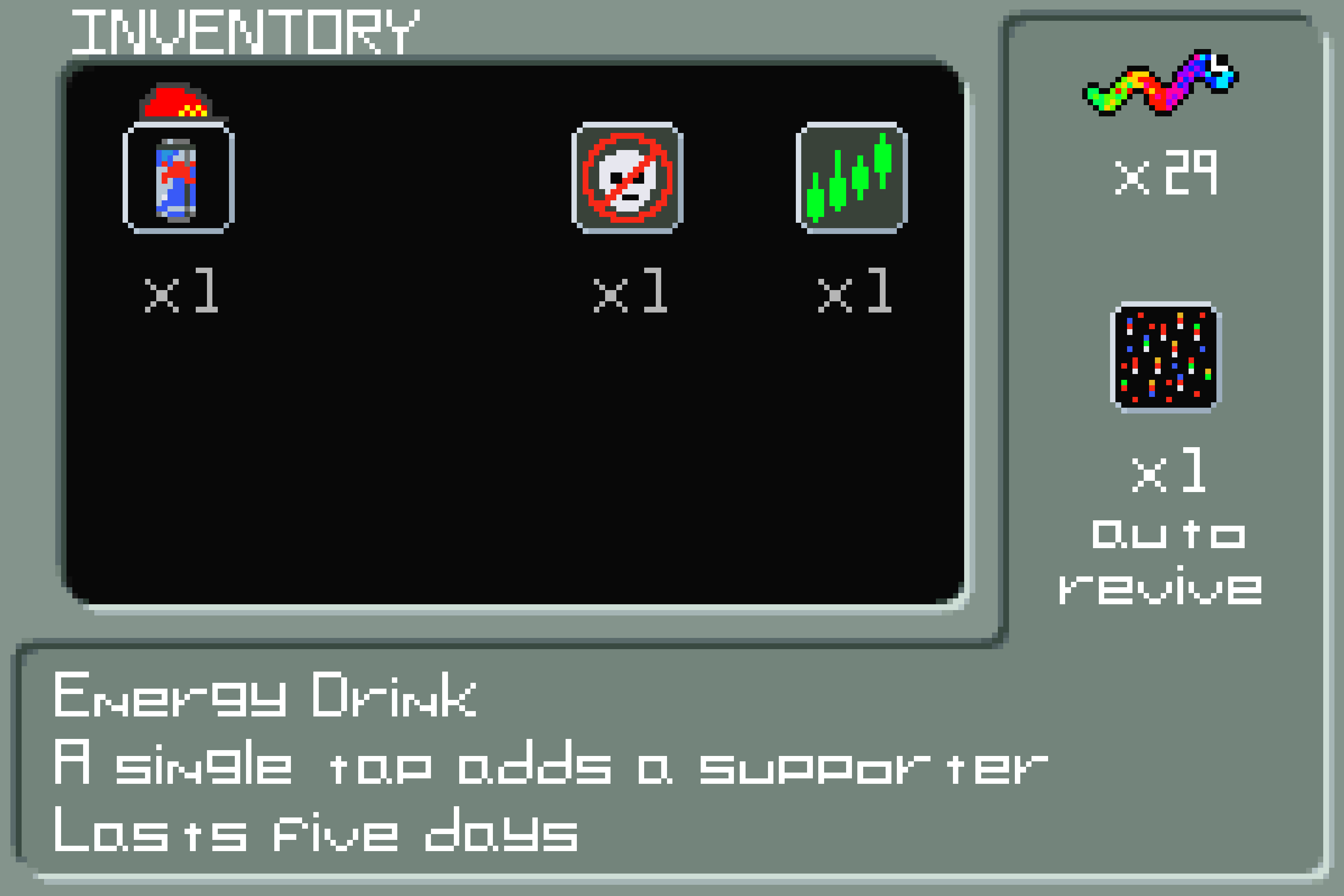

But, just like everyday life, people have their own lives to deal with, and so, over the course of a day, all of your supporters will disappear. As a result, once every 24 hours, you have to rebuild your support otherwise the rock crushes the protagonist and the game is over.

All of the supporting characters are self-portraits by people I’ve invited who have been around for the last few years during the coldest crypto winter of all. Every single supporter in the game has shown up every day.

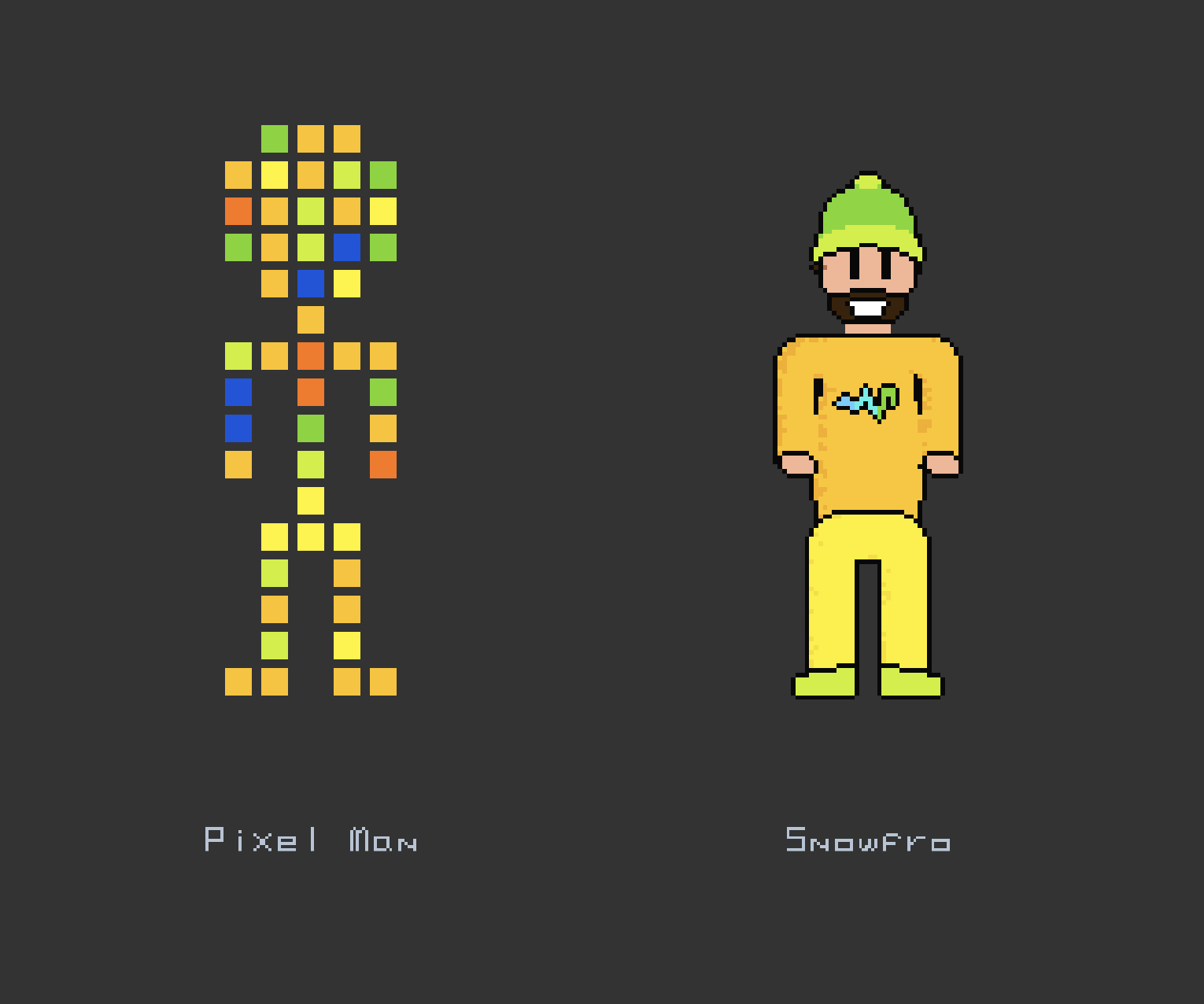

Video games are empathy machines, and when I sit down to play LIFT, I am not watching this stick figure that is supposed to represent Snowfro, I am that character.

Erick Calderon, better known as Snowfro, is an entrepreneur, artist, and technology enthusiast born in Mexico City and residing in Houston, Texas. He spent the first 18 years of his career operating a boutique ceramic tile company named La Nova Tile, working with high-end architecture and interior design projects across the United States. In 2020, he founded Art Blocks as a platform for on-demand generative art on the Ethereum blockchain. He released his own artwork, Chromie Squiggle — an algorithmic edition of 10,000 NFTs — as the first project on the Art Blocks platform. Calderon is a tireless advocate of NFTs as a technology, and is dedicated to elevating generative art as a medium of expression within the world of contemporary art.

Mitchell F. Chan is a conceptual artist based in Toronto, described by one critic as “committed to the most serious ideas of conceptualism in the most playful way possible.” His pioneering blockchain artwork Digital Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility (2017) was recently exhibited in “Monte di Pietá” at the Fondazione Prada during the 60th Venice Biennale. His most recent project, The Zantar Triptych (2025), is a series of real video games set inside a fictional video-game economy. It premiered at Nguyen Wahed in New York in 2025 and will be presented at Frieze Seoul next month by de Sarthe. Chan has written for numerous publications including Artforum, Right Click Save, and The Pembroke Observer.

Alex Estorick is Editor-in-Chief at Right Click Save.

___

¹ G de Chirico, “The Architectonic Sense in Ancient Painting” (1920), in M Carrà, Metaphysical Art, trans. C Tisdall, London: Thames and Hudson, 1971, 94.