Mario Klingemann’s exhibition “Early Works, 2007-2018” runs from September 25 to October 9, 2025 at Fellowship.

By spotlighting this seminal decade of the artist’s career, the exhibition proves that the hand coding of the Flash community precipitated a new ontology of posthuman collaboration.

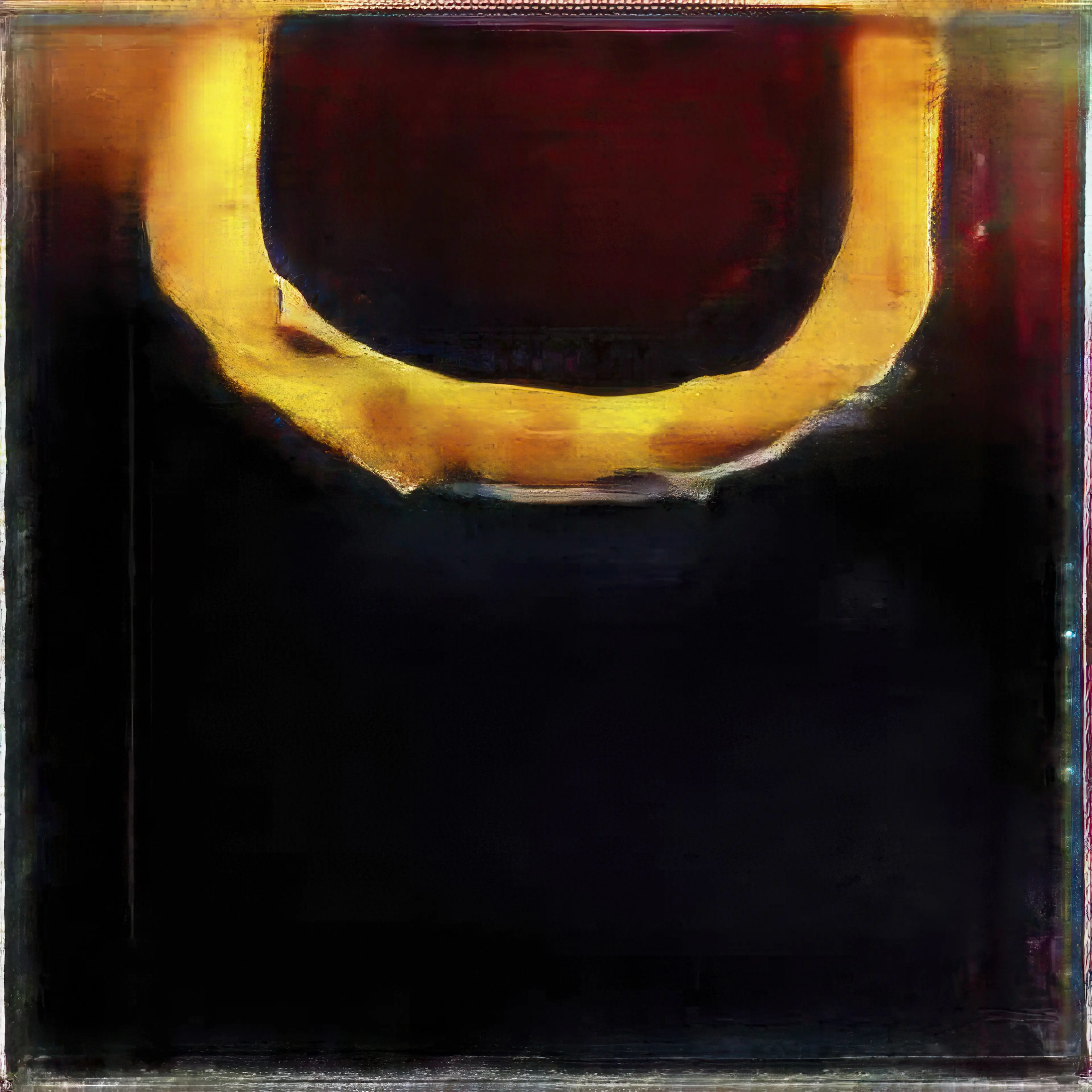

Instead of negotiating the machine’s autonomy in public, these works are private explorations of the border territory between human and nonhuman vision.

In the ideal world I would never have to produce any output. I would just enjoy the process… For me, the outputs are just a receipt that the system is working. (Mario Klingemann)

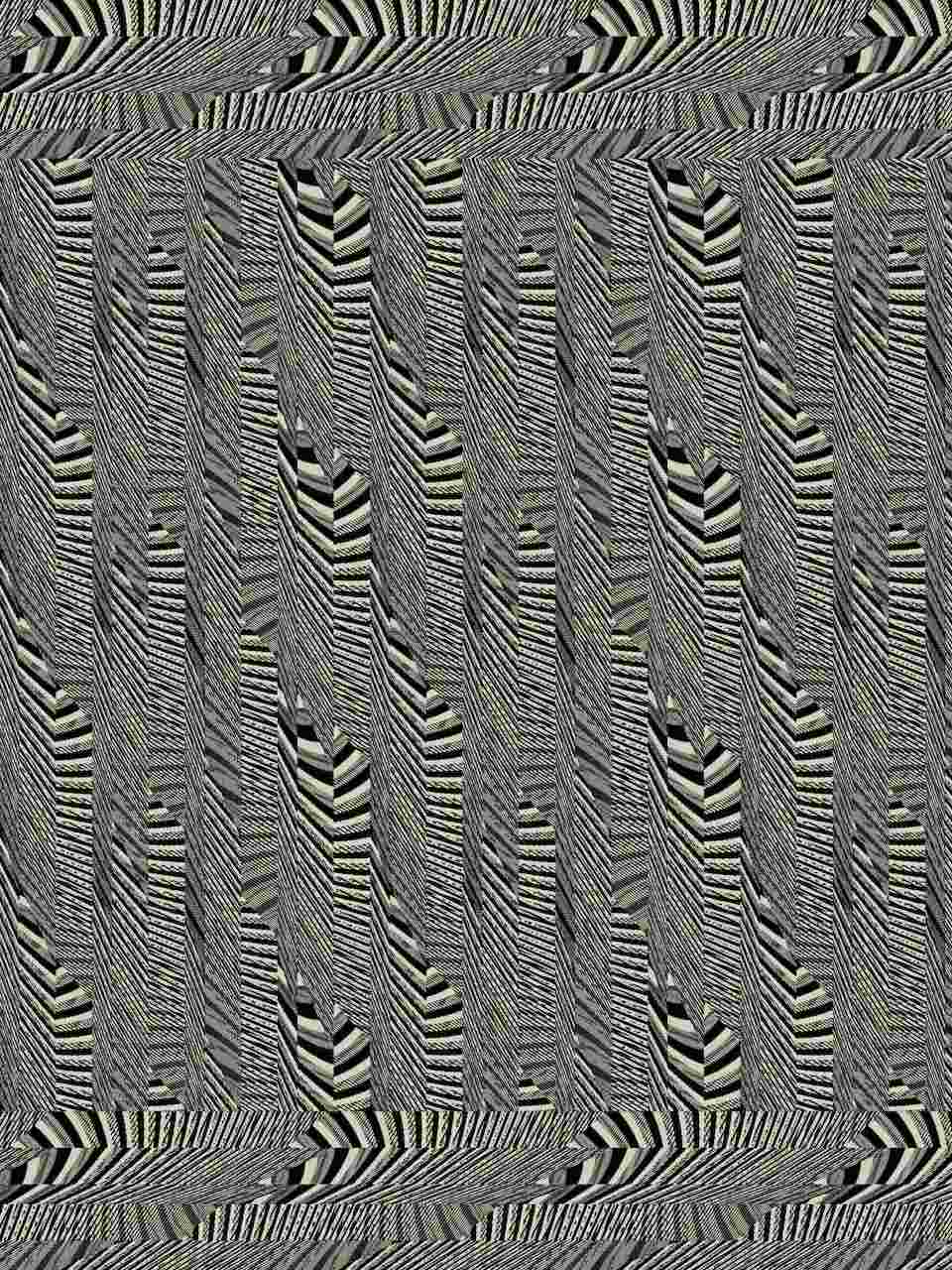

Consisting of modular algorithmic components, SketchMaker echoes early rule-based generative art in seeking to “tame randomness” in search of aesthetic “interestingness.”

Like all his works with machine learning, they carve out space between human and machine comprehension, but by emphasizing errors in representation they replace canonical genres with a state of aporia.

Mario Klingemann’s exhibition “Early Works, 2007-2018” runs from September 25 to October 9, 2025 at Fellowship.

Alex Estorick is Editor-in-Chief at Right Click Save.

___

¹ M Klingemann, interviewed by the author on March 4, 2025.

² S Lewitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art”, Artforum, Vol. 5, no. 10, Summer, 1967.

³ M Azar, “POV Data Doubles, the Dividual and the Drive to Visibility” in N Lushetich (ed.), Big Data–A New Medium?, New York: Routledge, 2020, 177-190.