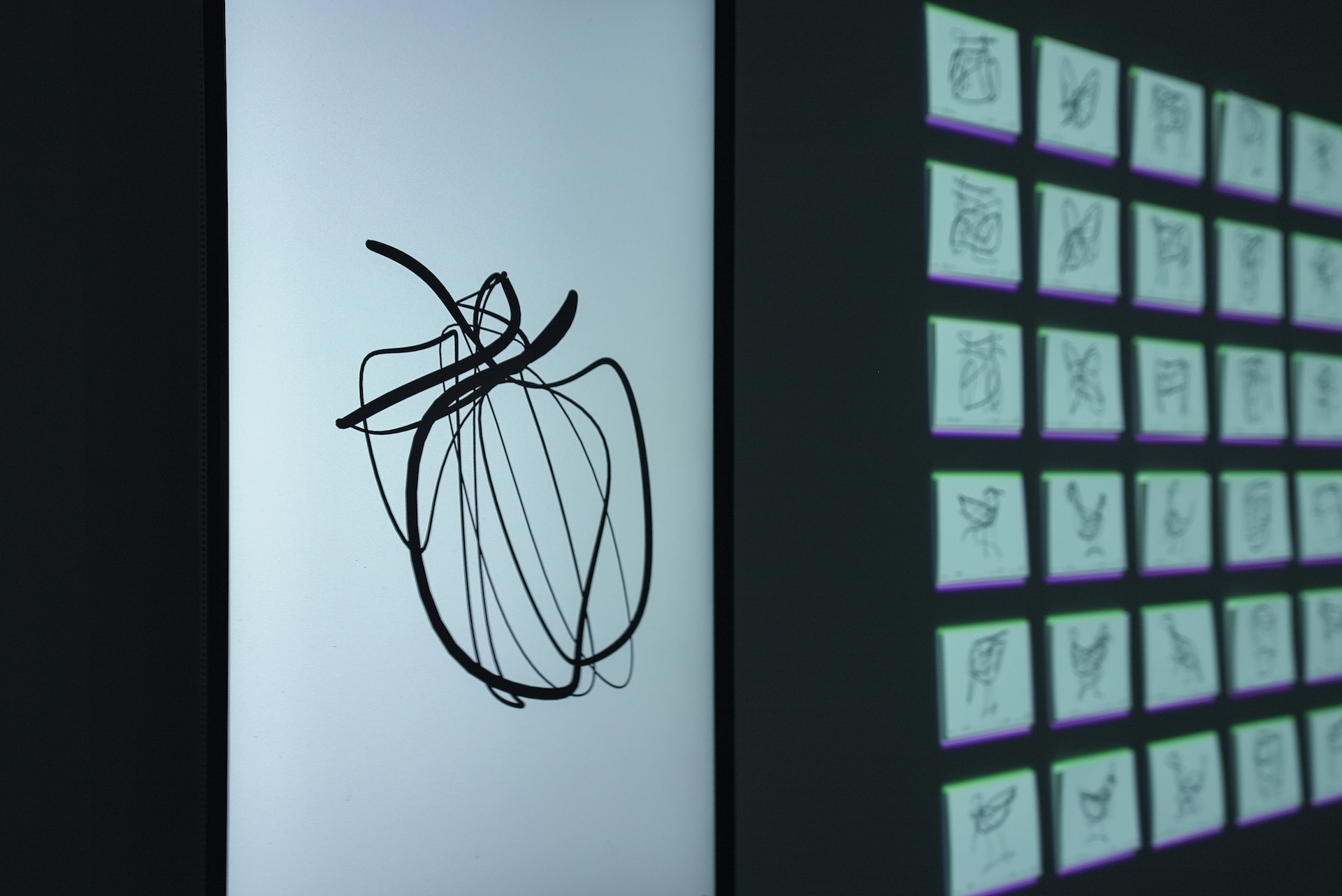

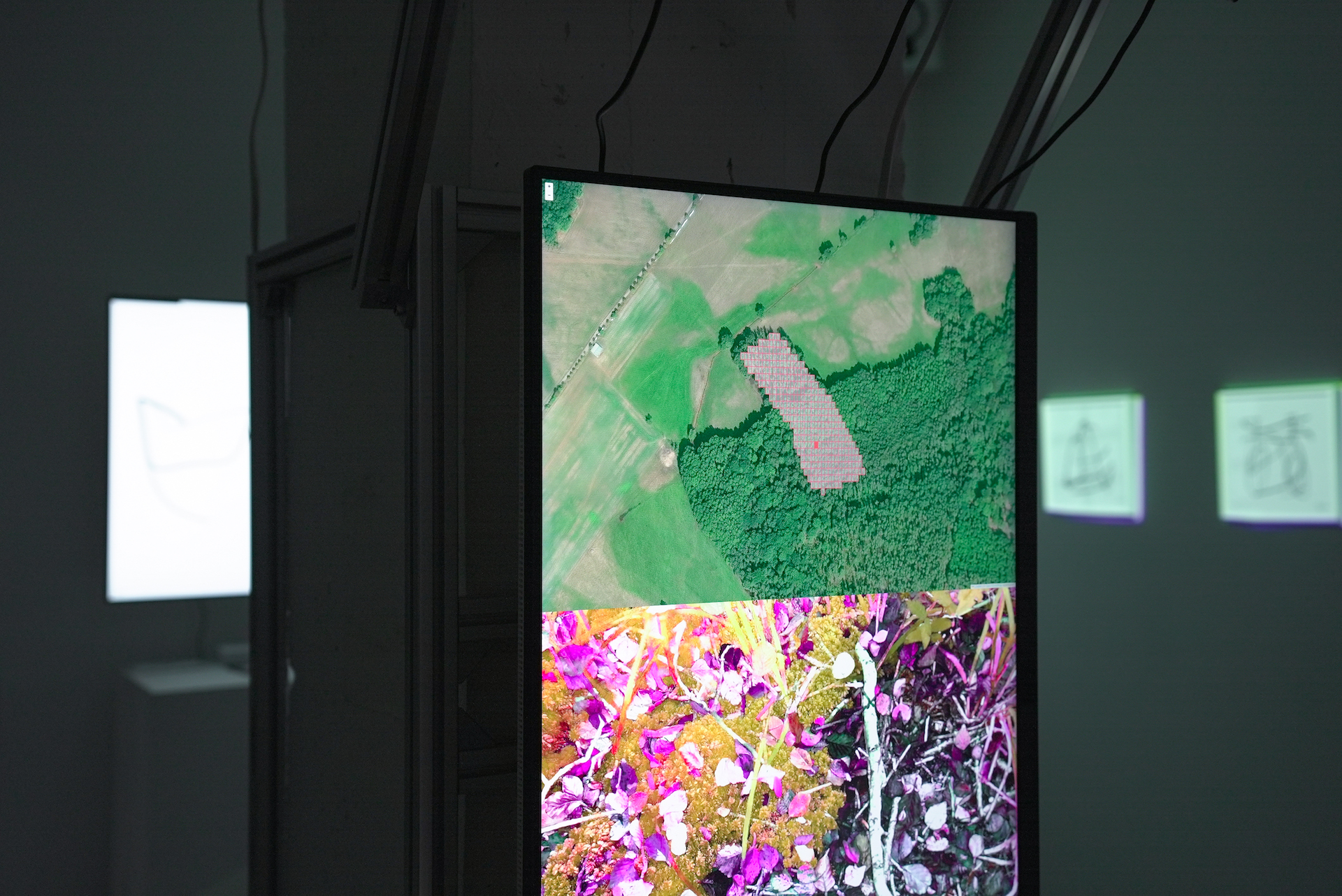

The exhibition, “Patterns of Entanglement”, runs to December 21 at NEORT++, Tokyo. Works by a number of participating artists are now on sale with Verse.

As the quantum scientist turned feminist philosopher Karen Barad astutely notes: “To be entangled is not simply to be intertwined with another, as in the joining of separate entities, but to lack an independent, self-contained existence. Existence is not an individual affair.”¹

Alongside weeds we can now point towards ecologies of AI slop, deepfake pornography, and radioactive and toxic rare earth element mines.

The prevalence of mutualistic relationships reveals that far from being dominated by competition — as implicit in depictions of life as the survival of the fittest — ecosystems are comprised of mutualistic, co-evolved assemblages.

Sy Taffel is a Senior Lecturer in Media Studies and co-director of the Political Ecology Research Centre at Massey University, Aotearoa-New Zealand. Sy’s research focuses upon the ecological, material, cultural, and political affordances of digital technologies. His current research project explores the intersections between digital technologies and postgrowth futures. He is the author of Postgrowth Digital Futures (Bristol University Press, forthcoming 2026), Digital Media Ecologies (Bloomsbury 2019), and an editor of Plastic Legacies (University of Athabasca Press 2021) and Ecological Entanglement in the Anthropocene (Lexington 2016).

___

¹ K Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007, ix.

² DJ Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

³ G Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971, 489.

⁴ E Haifa Giraud, What Comes after Entanglement?: Activism, Anthropocentrism, and an Ethics of Exclusion, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019, 176.

⁵ M Begon, CR Townsend, and JL Harper, Ecology: From Individuals to Ecosystems, Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006, 381/382.