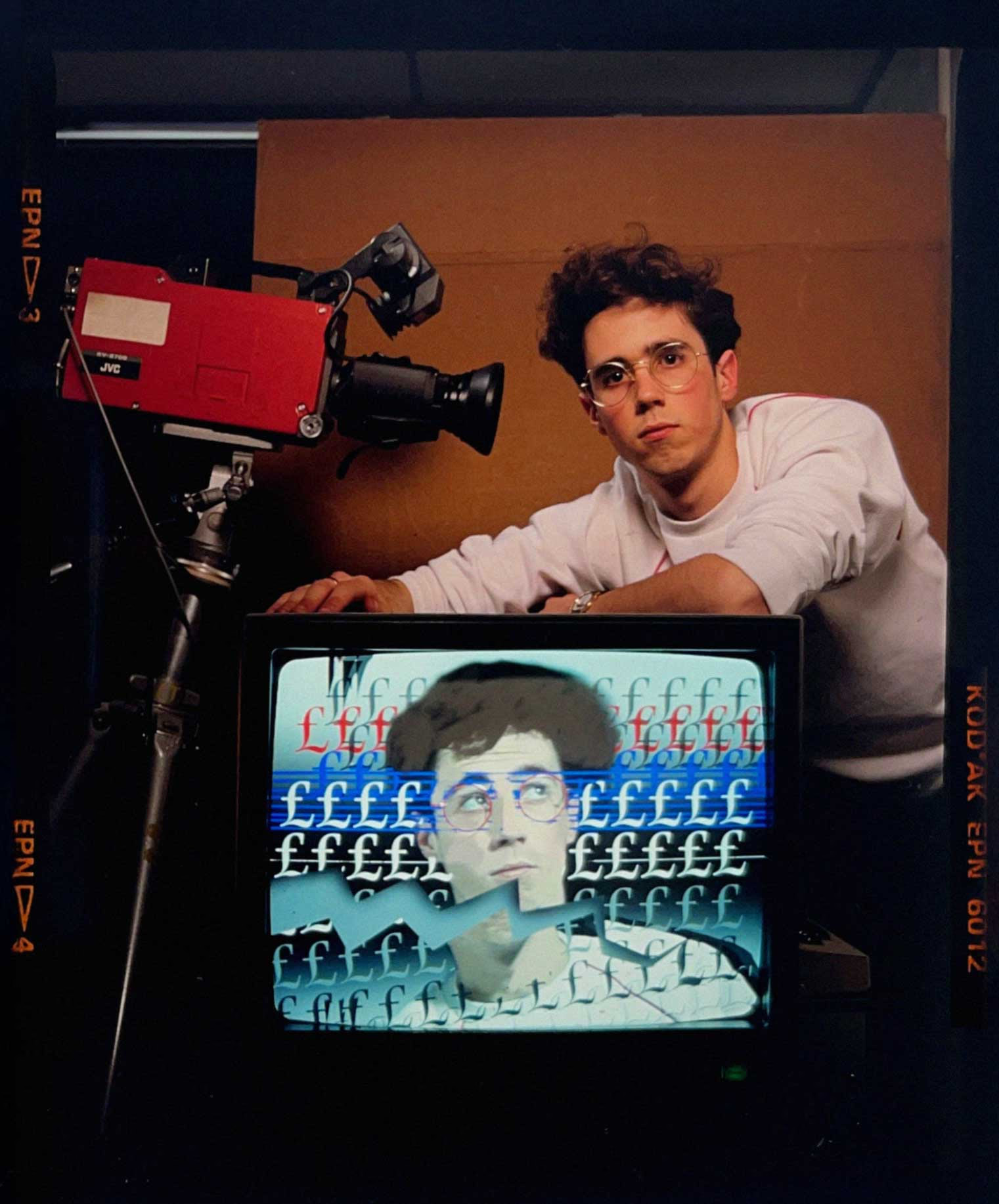

[The Paintbox] offered a completely new physiology and creative experience — a fusion of analog and digital, brush and screen. I began blending my Japanese ink drawings, photography, and typography in the Paintbox, creating what were among the first true multimedia artworks.

One of my first commissions was to develop the iconic graphic and animated identity for MTV Europe’s 1987 launch. That changed everything.

Somewhere along the way, I was dubbed the “Mother of Paintbox” — a title I still wear proudly.

It felt like working on the edge between analog and digital. That’s when the idea was born: to capture fragments of data, pixels suspended in time.

It was very special to be able to use this ancient graphic design tool that predated all the software that I have come to know in my creative life.

H: There’s a fundamental difference between our approach and that of Keith Haring. He came from a purely analog place, whereas we come from years of digital corruption.

When I arrived, they showed me a machine still being built, with an exposed motherboard, graphics card, and all. That moment inspired me. We usually think about the image on the screen, but it’s the guts of the machine that make the magic happen.

[The Paintbox] taught a generation of artists to build from scratch instead of relying on presets or prompts.

It might not be an exaggeration to say that Crypto Art as we know it would not exist without the Paintbox.

Georg Bak is an art advisor and curator specializing in digital art, NFTs, and generative photography. With a wealth of experience in the art industry, Bak has held senior positions at renowned institutions such as Hauser & Wirth and served as a fine art specialist at LGT Bank Fine Art Services. Currently, Bak offers his expertise to institutions and art collectors, focusing on the convergence of blockchain technology and art. He holds the role of art advisor to Le Random Collection and has provided guidance to esteemed organizations such as MoCDA, CADAF, and Rare Digital Art Festival #2. Bak’s influence extends to his involvement on the curatorial boards of SNGLR Art Collection and GENAP Collection. He has also collaborated as an independent curator with Sotheby’s, Phillips, and The Vancouver Biennale. Bak is the co-founder of The Digital Art Mile in Basel and NFT ART DAY in Zurich.

Bryan Brinkman is an award-winning multimedia artist based in New York. After graduating from the University of the Arts, Philadelphia with a degree in animation, he began a career in advertising and television, working as a graphic artist for acclaimed productions such as The Tonight Show and Saturday Night Live. In 2020, he entered the world of NFTs, merging his motion graphic skills with his passion for art and digital storytelling. Known for his vibrant colors and meticulous attention to detail, Brinkman’s works often explore themes of identity, perception, and the evolving relationship between humans and technology. The explosion of motion and colors that characterises much of his work takes Pop Art into the digital age and offers a playful commentary on creative processes and the NFT space. His works have been featured at Sotheby’s and Christie’s and on curated NFT platforms such as SuperRare, Nifty Gateway, and Art Blocks.

Coldie is a mixed-media artist whose signature stereoscopic 3D works have become synonymous with the visual language of crypto art since 2017. With a distinct fusion of historical commentary and financial critique, acclaimed series such as “Decentral Eyes” and “Filthy Fiat” explore the shifting power dynamics between blockchain technology and traditional financial institutions. As a leading voice in the rare digital art space, Coldie’s work has been featured in museum exhibitions, international cryptocurrency events, and esteemed auction houses, including Christie’s (New York), Sotheby’s (New York), and Bonhams (London).

Alex Estorick is a writer, editor, and curator based in London. As Editor-in-Chief of Right Click Save, he seeks to develop critical and inclusive approaches to emerging technologies. He is also a Visiting Research Fellow in the Department of Computing at Goldsmiths, University of London. He writes for various publications, from Artforum to the Financial Times, and was lead author of the first aesthetics of crypto art. His edited volume, Right Click Save: The New Digital Art Community (2024), is published by Vetro Editions.

Hackatao are an OG Crypto Art duo that began their symbiotic adventure in 2007: “Hack” to unveil the unseen and “Tao” for the dance of duality. The duo blend physical and digital techniques into a singular style. In 2007, they created their first iconic Podmork and nearly a decade afterwards they took their place as pioneers of Crypto Art, when they minted their first NFT, Girl Next Door, in April 2018, shaping the ecosystem by advocating for royalties on secondary sales. Hackatao continuously explore new mediums, from physical canvas and sculptures to the AR/VR realms, through the PFP scene with Queens + Kings, to generative art, as seen in Aleph-0 and an upcoming mathematics-driven project, to music, cinema, and philately. They are currently creating a series of short animated films with Q+K avatars as protagonists. Hackatao’s eclectic spirit extends to partnerships with Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and cultural icons like Blondie. They have worked with institutions including the Austrian Post, ensuring their legacy as storytellers in the ever-expanding digital art world.

Kim Mannes-Abbott is a pioneering digital artist and designer whose early adoption of Quantel’s Paintbox in 1984 helped shape the future of multimedia art. As an undergraduate at Middlesex University, she won the ICA New Contemporaries Competition with a groundbreaking series blending Paintbox and mixed media. In 1987, she developed the iconic graphic language for MTV’s European launch, cementing her influence on a new digital visual culture. Her work has been exhibited internationally and featured on the cover of the iconic Paintboxed! book. Most recently, her digital creations have been shown at Tate Modern and the National Portrait Gallery. Kim is also a multi-award-winning Design and Creative Director and founder of KM/A Liquid Design, where she continues to merge branding, design, and art.