Alex Estorick: In what ways does your combined practice draw on your individual priorities as artists? Does it feel like more than the sum of its parts when you are pooling knowledge into hybrid forms? Is anything lost?

Wen New Atelier: Our collaboration grows very naturally out of who we are as individuals. Kalen is a writer and translator with a love of puzzles and games. Growing up in Canada to Korean-Japanese parents and between multiple languages and cultures, she’s always navigated the world from a place of in-betweenness and has a natural impulse to bring disparate elements together into a whole.

Julien comes from a fine-arts background; he holds an MFA and studied painting, sculpture, and installation among other things, and has a technophile’s curiosity. He’s not an engineer, but he has the instincts of a tinkerer — a kind of poetic mad scientist. Wen New is really an alchemy of those two positions. We like to say that our work dwells in the spaces between media, disciplines, languages; between literature and art, and the physical and the digital.

This liminality also applies to our practice in general: the atelier lives in a third space between Kalen and Julien.

We’re also a married couple, and because we share our lives as much as our work, the dialogue is constant. Concepts and ideas for projects often emerge from our conversations and continue to develop organically as we go about our day, over breakfast, while playing with the kids, and on our afternoon walks. You could say that we’re also creating in the spaces between work and life.

AE: In a world struggling for attention, how important is meaning to your practice?

WNA: Our work is deliberately polysemic, and the viewer can practice different modes of reading when engaging with it: they can skim the surface, or they can read closely, teasing out hidden threads much like with a text.

It’s the excess, the limits, the transgressions, and the slippages of language that interest us, because where language breaks down, it also breaks open, revealing its own structure. We like orchestrating those moments — introducing a grain of sand that makes the system stutter, so that we can expose its mechanics.

The signification process is an experience we want viewers to activate when engaging with our work. We believe humans are meaning-making machines, and we can’t help but read into things and assign significance. When we create literature machines like Couple Machine (2024) or computational poems like Hai-Tech (2025), both of which generate infinite, random combinations of words, we’re really interested in the reader’s experience.

Sublime, uncanny, or nonsensical outputs invite viewers to activate the signifying chain, to project their own experiences, memories, and desires into the text, and in doing so, co-create meaning with the writer, whether machine or human. This co-creative process feels especially important now, when we’re drowning in an overabundance of text with the mainstreaming of AI.

Attention is currency and we’re all in short supply.

Given this reality, our work also addresses the overproduction of text, most notably through the process of recombining, reshuffling, recycling, and remixing existing text. For instance, the Miniscriber (2025), our conceptual poetry synth, proposes a new mode of writing that is inspired by the thesis of the conceptual poetry movement — remixing and sampling pre-existing text instead of adding more to the linguistic deluge.

AE: Your works carry a playful irreverence as both conceptual projects and technical objects. Their rigor and gentle appeal to technostalgia makes me think of Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby’s book, Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects (2001), but by bringing digital art into the physical space of the gallery they also recall postinternet practices. How would you describe your work, which seems to live at multiple intersections?

WNA: We’re delighted by your description, because it touches on so much of what we’re trying to do. Playfulness is certainly a guiding principle in our work. Conceptual art has often been perceived as austere and hermetic, and we like to counter that by introducing an element of play and levity.

Our works sometimes take the form of speculative devices that look like familiar objects: a keyboard, a synthesizer, a book. They borrow from consumer technology and industrial design, but they have no purpose outside themselves. They do nothing “useful” in the conventional sense, which helps blur the lines between art, design, and cultural production.

In that sense, we feel close to Dunne & Raby’s idea of critical design — using objects to question rather than to solve. We try to reimagine technology and our relationship with it in order to reclaim agency over the devices and systems that increasingly define our lives by thinking about them differently and imagining alternative, poetic ways of engaging with them.

We also adhere to Marisa Olson’s understanding of postinternet, not as the death of the internet, but as a way of making art in a world fundamentally shaped by it — a world where digital technologies, algorithms, and networks structure how we see, think, and create. As artists, it feels essential to engage critically, aesthetically, and poetically with these contemporary realities. We’re living through a turning point in the history of textual practice: the book, the screen, and the code are converging, and we feel it’s important to reflect on this, on what it might mean, and where we might be going.

AE: Jasia Reichardt, who curated a number of iconic exhibitions at the ICA in the 1960s such as “Cybernetic Serendipity” and “Between Poetry and Painting”, has described concrete poetry as the first international art movement with a common idea. It feels appropriate that you are now exhibiting a trio of works at a show of “Computational Poetry” at NEORT++ in Tokyo. What is the relation of poetry to computing and what makes Japan a natural place for such discussions?

WNA: Jasia Reichardt’s vision feels newly relevant in an age when code has become a universal language. Zeroichi Arakawa’s exhibition statement for “Computational Poetry” astutely points out the ubiquity of code today, and how poetry is not impervious to its structuring of our world:

If we think in language, and if language is the essence of poetry, then in our present — when our world is structured through code — poetry must also be thought through code. (Zeroichi Arakawa)

What also struck us was Arakawa’s notion that execution — the act of running code; the event of execution — is the new voice of poetry, especially when considered alongside Auden’s claim that “poetry makes nothing happen.” What makes this exhibition so exciting is the variety of ways in which the poet-artists explore the connection between computing and poetry.

Arakawa’s own brilliant work, Executed Poetry (2025), are short Python poems executed on microcontrollers that treat code as both text and event; Michelangelo’s code runs his mesmerizing asemic script; Nahiko’s MONEY (2025) embeds the word across every layer of the digital object, creating an omnipresent verse; while Akihiro Kubota composes quantum code-poems in newly invented languages, turning structures of quantum computation into poetic systems that merge philosophy, science, and aesthetics.

AE: What was your intention when choosing works for the exhibition?

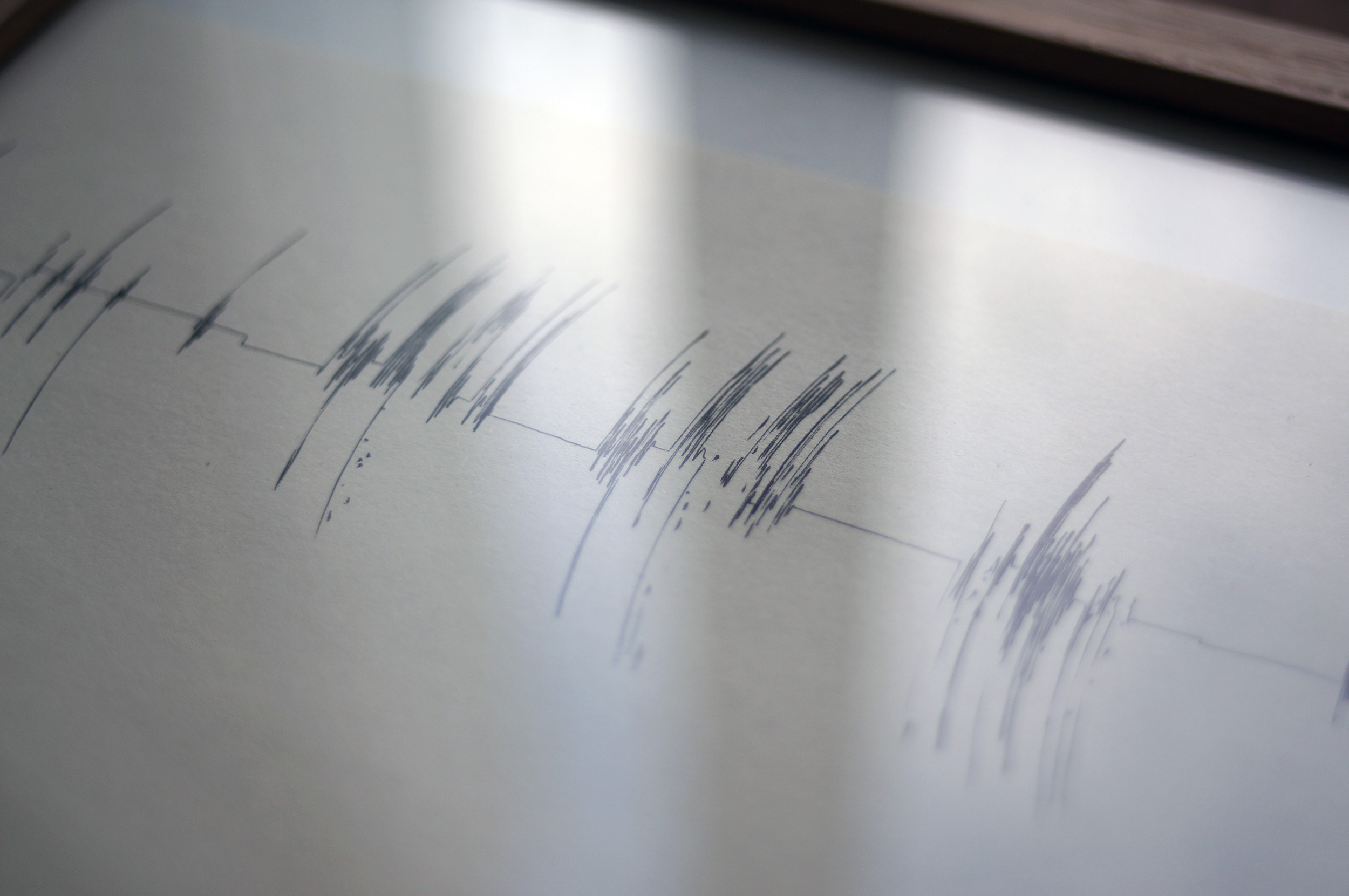

WNA: The other curator, Yusuke Shono, selected Miniscriber and Data Waves in the Rising Sun (2025), which are both visual code poems that highlight the materiality of language and use remixing as both an aesthetic and conceptual strategy. He invited us to contribute a third piece and Kalen had always wanted to create a work in Japanese, so we took up the challenge and created Hai-Tech, a generative poem that bridges haiku tradition and digital culture through code.

Noriaki Nakata and the curators of the exhibition, Yusuke Shono and Zeroichi Arakawa, did an exceptional job of installing each work in a way that honored the intentions of the artists. For example, Data Waves in the Rising Sun — a code poem that recreates the visual effect of water sparkling in the sun — was run on a spotlighted screen lying on the floor.

AE: Do you see your work, as well as asemic writing, as ways of helping audiences to explore the space between human and nonhuman codes?

WNA: Asemic writing looks like language but resists meaning. It’s meaningless, yet feels like it should mean something, which reveals our meaning-making impulse. It’s beautiful, but its opacity and “meaninglessness” can frustrate our attempts at understanding.

When we work with machines and code, we’re engaging with another kind of language that mirrors us while remaining “other”. We’re interested in that relationship, especially how the nonhuman shapes what we think of as human. As that relationship gets more and more entangled, with AI-produced images and texts confounding our categories, it can be unsettling. Those spaces at once human and synthetic are fascinating to explore.

AE: Sasha Stiles once described poetry as “the original blockchain.” Does the idea of poetry as a technology resonate with you, and how important is the blockchain to your practice today?

WNA: Yes, poetry has been a medium for encoding experience and aiding memory, and we love Sasha’s way of bringing together seemingly distant ideas and connecting them in novel ways. We also relate to the inverse: the idea of code — the language of technology — as poetry, something Arakawa’s curatorial text articulated beautifully.

We’ve been involved in the blockchain space since 2020, through its cycles of hype and disillusionment, and we’ve continued experimenting because we still see it as fertile ground for artistic exploration. With the coding support of Zeroichi Arakawa, we were able to make our Hai-Tech series our first on-chain generative project. Each piece was generated at mint, something uniquely possible on the blockchain.

The “Computational Poetry” exhibition has inspired us to go further — to think more deeply about code and smart contracts as poetic instruments, and about the blockchain not only as infrastructure, but as a new kind of publishing space for computational literature.

Of course, our name Wen New is itself a playful nod to crypto vernacular. It has multiple meanings, including that collective impatience for “what’s next”.

Kalen Iwamoto and Julien Silvano are the art couple behind Wen New, an atelier that exists at the intersection of art, language, and technology. Their polysemic works, at once playful and critical, lay bare the ambivalence of contemporary digital life and advance alternative ways of imagining, using, and relating to text and technology. Through conceptual prisms such as speculative literary devices, the design of imperfection, or performance writing, the duo researches and experiments with unconventional reading and writing practices that open up our experience with text, employing détournement to subvert and reframe meaning to reveal hidden structures within language and technology.

Julien Silvano, who holds an MFA (DNSEP) from the school of Fine Art in Grenoble (École Supérieure d’Art de Grenoble), has tinkered with technology and sculptures from an early age, while Kalen Iwamoto, raised between two languages and cultures, embraces ambivalence and play in her relationship with language to explore its structures as both constraint and possibility. Together, they have produced literature machines, book-objects, paintings generated from procedural writing on text, a blockchain play co-written with AI, and other works that straddle the physical and the digital, and literature, and art. Their work was a finalist for The Lumen Prize in 2025, and has been exhibited in Paris, Tokyo, New York, Berlin, Budapest, and beyond. They are based in the countryside outside Lyon, France.

Alex Estorick is Editor-in-Chief at Right Click Save.