I was the kind of kid who took things apart, even building a one-dimensional Lego pen plotter to record Morse code.

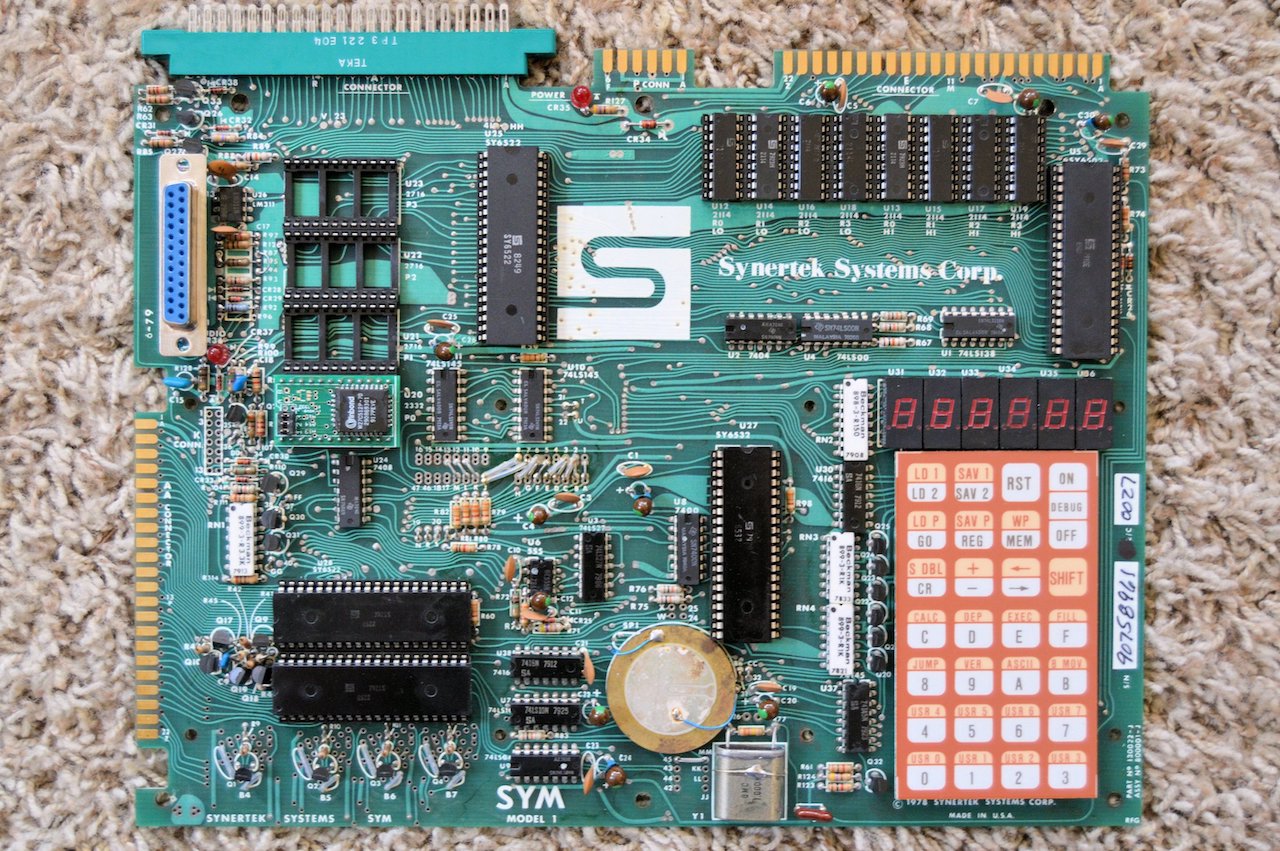

As a broke painter building computers from office skips, I had to find a way to continue working as an artist. Finding the Algorists online, especially Roman Verostko, I felt an affinity. I noticed that they used pen plotters, so I bought some cheap second-hand ones to explore drawing from a distance.

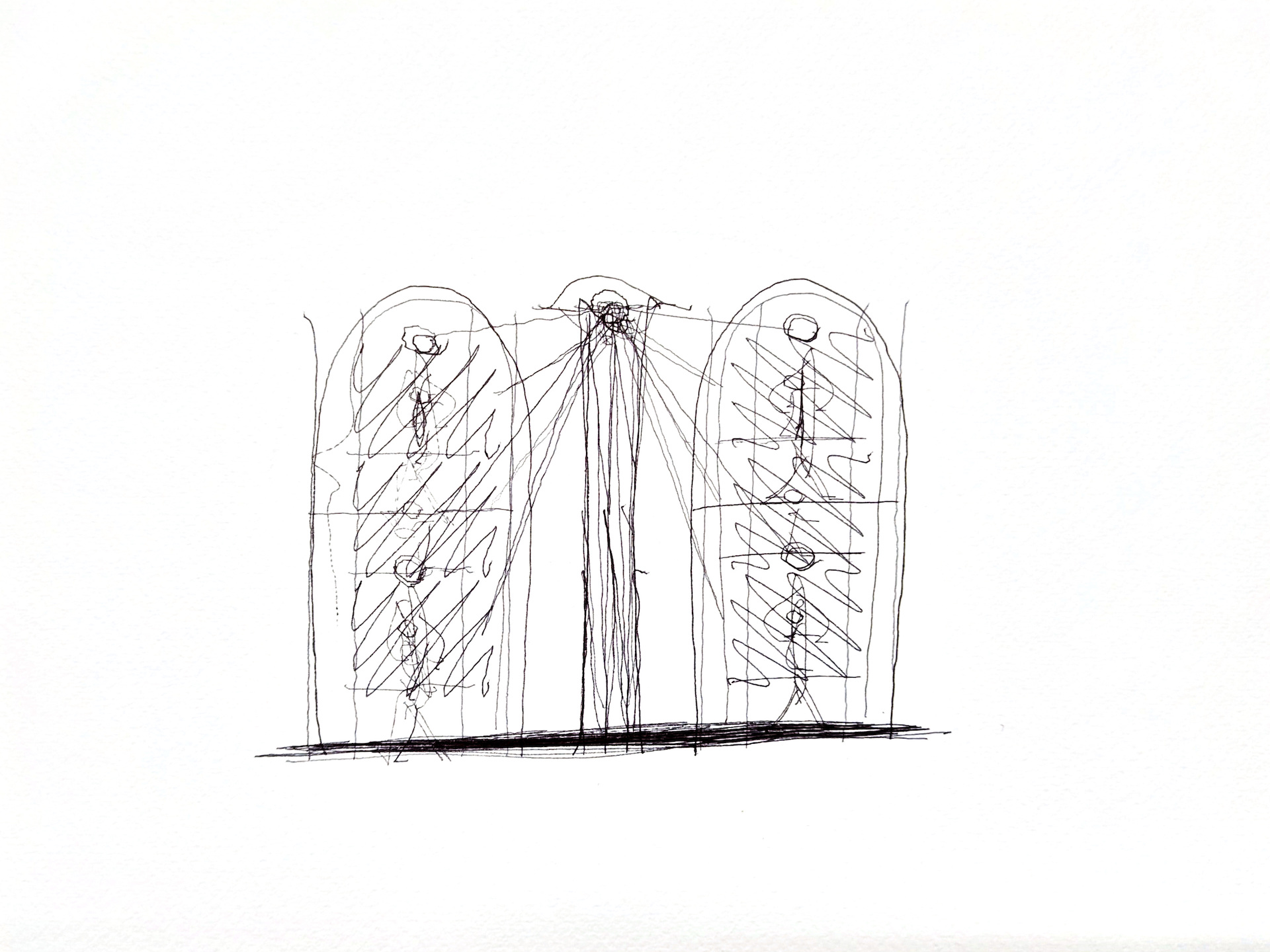

It’s interesting that I’m better known for these performances than the drawings themselves. Harold Cohen told me he stopped exhibiting his machines because they hid the works; I embraced it!

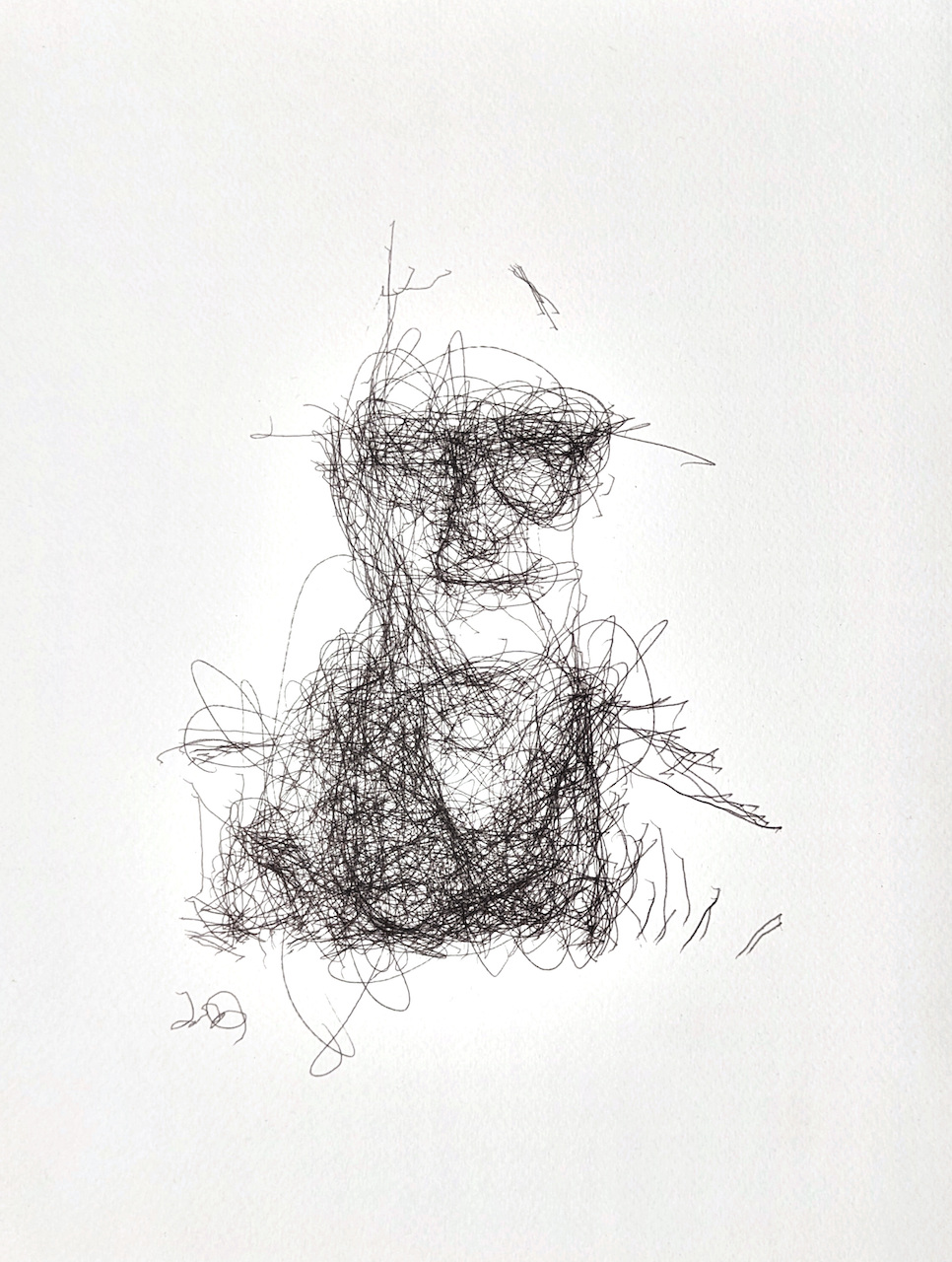

After years spent using systems to distance myself from the process, I noticed an absence in the drawings: me. While that had actually been my original aim, I decided it was time to put myself back in.

The agents’ styles and personalities are childlike but immensely cultured. The project uses the literary trope of the outsider looking in on a society.

I don’t see these systems as artists, but as machines that are perceived as artists. They are simulacra, but when I work with them, I forget that.

Working in academia since the early 2000s has allowed me to meet many pioneers of computational art.

Perhaps the work touches people because robots are, in a way, behavioral self-portraits. For me, the purpose of art is to give artists a place in society. It is the only thing I can do; but it is a privilege granted by audiences. I like to give people experiences; the drawing is only one part of it.

The system works with many layers of glaze and impasto, similar to Old Masters such as Rembrandt and Goya. The process involves the robot applying a layer of thick white paint to a gray background. Once dry, I apply a transparent colored glaze. The robot takes a picture, plans the next strokes, and the cycle repeats itself.

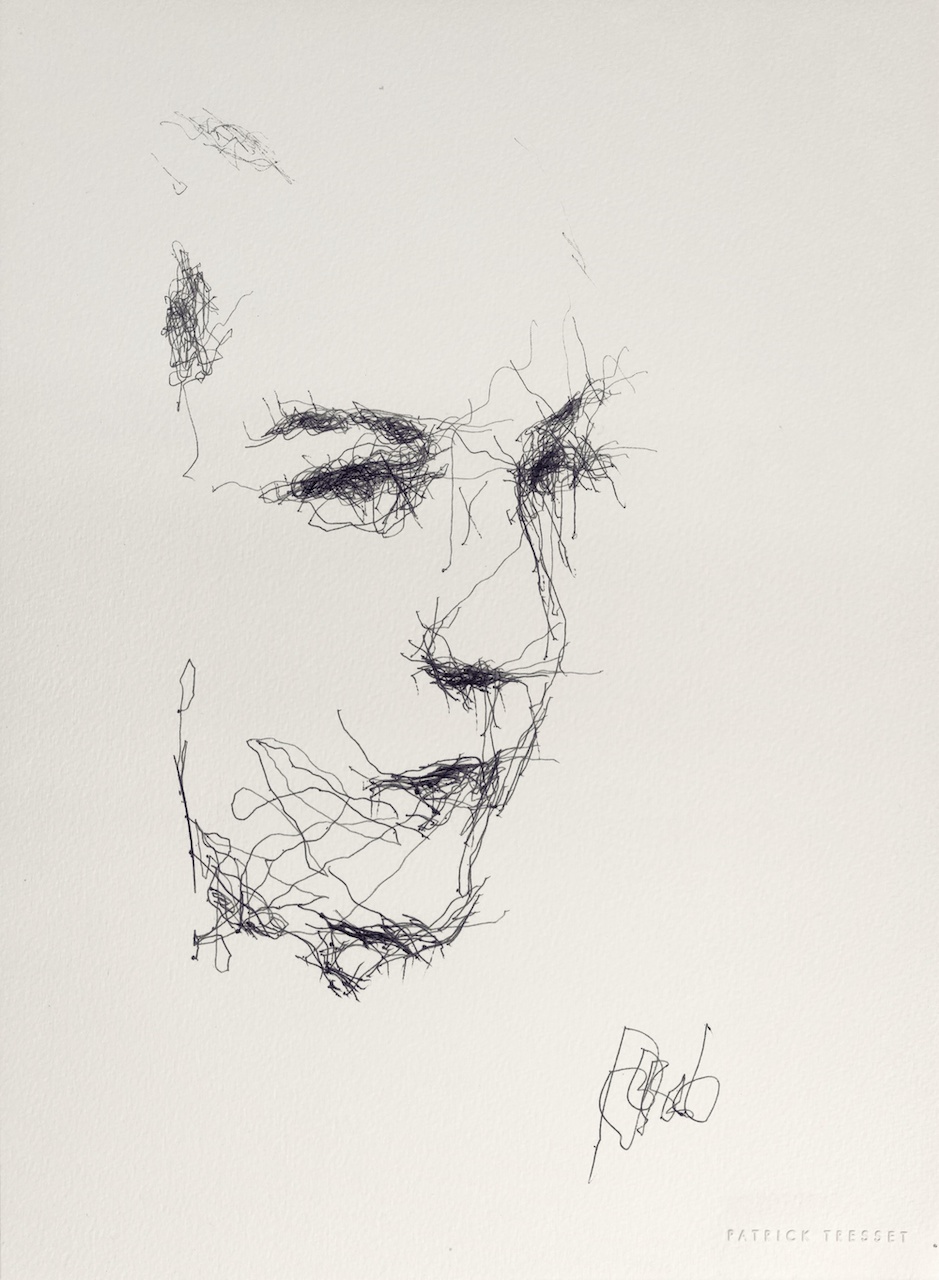

Patrick Tresset is a Brussels-based French artist known for performative installations that explore humanness through computational systems, AI, and robotics. He holds a Masters and MPhil in Arts and Technology from Goldsmiths College, London, and has served as a senior research fellow at the University of Konstanz and a visiting adjunct professor at the University of Canberra. Although focused exclusively on his art practice for the past decade, his research is referenced in over 300 academic publications. Since 2011, Tresset has held sixteen solo exhibitions, participating in group shows at major museums including the Centre Pompidou and Grand Palais, Paris; Prada Foundation, Milan; V&A, London; MMCA, Seoul; Bozar, Brussels; Taikang Art Museum, Beijing; and the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo.

Tresset’s installations, paintings, drawings, and digital works are held in public and private collections and have been awarded by Lumen, Ars Electronica, the Liedts-Meesen Foundation, and the Japan Media Arts Festival, while in 2017 he was nominated as a WEF Cultural Leader. A monograph, Patrick Tresset: Human Traits and the Art of Creative Machines, was published in 2016.

Alex Estorick is Editor-in-Chief at Right Click Save.