The work of Carla Gannis is currently on view as part of “TRANSFER Download: AliveNET” at Nguyen Wahed, New York. The exhibition runs to 19 March, 2026.

I’m less interested in what technology promises than in what it reveals, amplifies, or obscures. My work is obsessive and performed consciously through a prismatic self that contends with fantasies of coherence and optimization.

Through this alter ego, who metaphorically hacked into websites to sing cyber ballads about corporate greed, chauvinism, and desire for something real, I could be a full-fledged artist without apologizing for my weirdness and audacity.

I once described the work as an ontological metanarrative in which “I” and “I” converge: a human body moving through a not-yet-denatured landscape, and a virtual body traversing a constructed one. The central question I was posing was: who are we as 21st-century minds and bodies, existing within porous frameworks of sublime natural and technological environments?

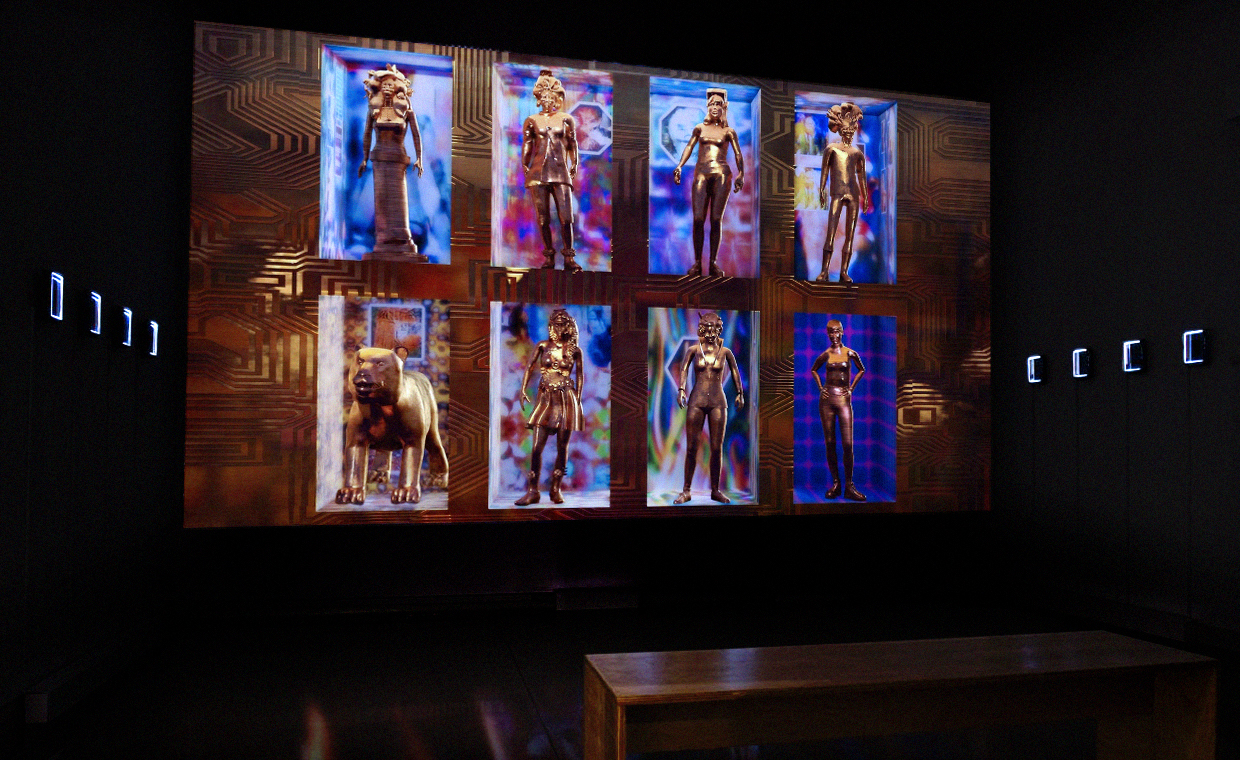

Taken together, these avatars are no longer stand-ins for me alone, but signs and signifiers of broader identity formations and cultural constructs that are increasingly being adopted and remodeled by machine systems.

The return to making physical objects, and then feeding them back into AI and digital systems after they’ve been touched and marked by me, feels like a direct response to the flattening I see across many contemporary systems: product design, AI image generation, and even “looksmaxing,” where everything and everyone begins to converge toward the same homogenous aesthetic.

Model Of Me highlights the ways digital systems homogenize human experience, the hubris embedded in privileging our own senses, and the quiet liberation of resisting technological beautification. It asks what it means to be seen by a system that can learn almost anything — except what it feels like to live, age, and let go.

Strangeness opens a space where critique doesn’t have to arrive in a straightjacket of seriousness; humor becomes a way in, a pressure release, a loosening of the buckles, if only for a moment.

Once your work operates at that scale, the myth of the lone genius is difficult to support.

I think of myself as both author and co-author — scraping my own fuzzy brain much less efficiently than a machine — to recombine ideas that have circulated in human consciousness for millennia.

Someone once described my work, The Garden of Emoji Delights, as “accessible”. At first I took it as an insult because I’d been trained in graduate school to hear words like accessible, pretty, interesting, or illustrative as among the most humiliating adjectives an artist could receive. But accessibility can be a Trojan horse; accessible work invites viewers in before they realize they’re being asked to sit with something uncomfortable.

The art of Carla Gannis is characterized by a commitment to experimentation. Working with an array of media, the maximalist nature of her practice reflects the hypermediated conditions in which she searches for loci of identity, meaning, and belief. Known for using humor as a tool for exploring complex issues, Gannis’s work has been exhibited globally in exhibitions, screenings, and internet projects. She also teaches “healing-edge” technology as an Industry Professor at New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering in the Department of Technology, Culture, and Society. She is a Year 7 Alum of NEW INC in the XR: Bodies in Space track, and holds an MFA in painting from Boston University and a BFA in painting from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Eva Yisu Ren is a New York-based advisor and founder of VEO Advisory, working across the primary and secondary art markets. She has held positions at Alisan Fine Arts, Chambers Fine Art, Christie’s auction house, and The FLAG Art Foundation. Ren also co-founded ONBD, a digital art hub and cultural platform advancing digital artists through curated exhibitions, editorial programming, and ecosystem-building. A graduate of New York University’s MA in Visual Arts Administration, her TED Talk, “Humanity On-Chain,” explores how technology reshapes culture and identity.