“Infinite Images: The Art of Algorithms” is at Toledo Museum of Art until November 30

Louis Jebb: How do you think Infinite Images, and your contribution to it, helps to define generative art in 2025?

Julia Kaganskiy: Part of the reason that I wanted to do a show focused on generative art, at this moment, is because the definition of generative art is something that is in flux; and not very well defined. If you speak to the Web3 community, they have a particular definition of generative art versus if you speak to someone who's coming from a generative AI perspective.

I thought it would be really useful to dig into this term and to map the landscape of what is generative art, what has it been, what tools and processes have been used, what kind of works have been created with it over this 60-year time period.

[Because] for a lot of people who are not familiar with [...] digital art in general, digital art, generative art equates to AI. [There is…] the assumption that any form of digital art is going to be AI or that there's no kind of human creativity in it. [This] is something that I think we need to work to dispel because it's a huge misconception that is [around] right now because of the controversy around generative AI and the way that it scrapes people's work from the internet and turns it into things created by private companies who are profiting off that.

The issues that are being raised are very important around intellectual property, around the environmental impact of these tools around job security in the future for a lot of different professionals. All of this is super valid. But I think there's a flattening that is happening in the public perception where it's creating a lot of knee-jerk reactions against anything digital, especially in the art space, that I think we need to try and push against. I actually welcome these conversations because then it opens up the door to having these more nuanced discussions about what does it mean for an artist to build their own software? And how is that different from someone going to ChatGPT and typing in a prompt?

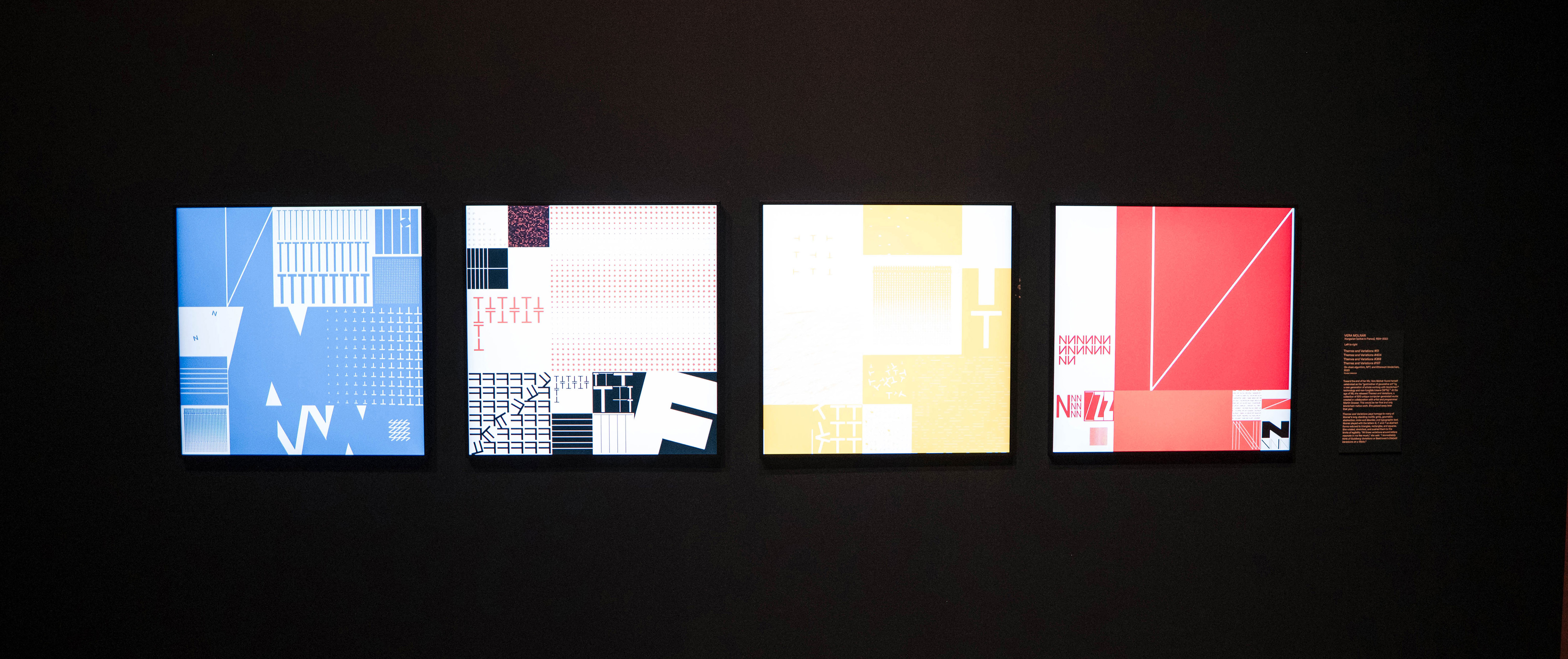

Casey Reas: The exhibition’s first room sets the stage for the rest. This room could be in any encyclopedic art museum: Josef Albers, Anni Albers, Max Bill, Sol LeWitt! The selection of works by Vera Molnar are the bridge from mid-20th-century art to the 21st-century works in this show.

I agree with you entirely, the nomenclature around “digital” and “generative” is confusing within the field and it’s entirely opaque to the general public.

However, I saw the public in the show during the opening weekend and I saw people really engaging with the work, from kids to seniors. So, we have the gap between the work, and the vibrance of the experience with the work, and the language around it.

Sofia Crespo: I’m not sure any work on its own “clarifies” what generative art is. What it does, together with the other pieces in “Infinite Images”, is highlight how diverse generative practices actually are.

There are code-based systems, works where AI is used, more procedural or rule-based approaches, and pieces that sit somewhere in between. For me, that diversity is the message that generative art is not a single tool, but a spectrum of practices.

Anna Ridler: I absolutely agree with Sofia. One of the things that is interesting is that “generative” is a word that can hold so many different types of works and practises and is more expansive than what might typically be assumed (something that has been really brought out in the exhibition). It also has lots of associations and connotations outside of the art world, which also I think get brought in whenever you try to truly unpick what it might mean.

Sam Spratt: I can’t say I see it as an issue in need of clarifying but I am not a purist so it’s not my wall to defend. People can and will call this whatever they want regardless of the exhibition — what is or is not generative art, is or is not AI, is or is not digital. Dominion is learning the nuances to name the difference; but that demands curiosity and the exhibition invites curiosity. It is filled with human contributions to a pretty stretched definition of generative art to a purist, but is segmented in such a way as to create dividing lines within that, whether you best access it in print, on screen, in interactive code, immersive instal or, in my case, a room full of people and their stories [The Masks of Luci, 2025 and Masquerade, 2025]

What this exhibition does — what Julia’s curation allows — is to stretch the word “generative”. I won’t pretend that there isn’t a more technical definition to traditional generative art snapshotted in time, one that my contribution exists almost entirely outside, but I find the act of stretching its meaning to be pretty generative of her: iteration, mutation, emergence from the compounded efforts of humans all trying to wield or translate rules/principles/design/code/math/the god molecule.

LJ: How important was it to you that every work in “Infinite Images” is made by an artist or artists creating a generative system?

JK: One of the constraints that I had for the exhibition is that every work, every series in this show is created by the artists building their own generative system. Whether that is an algorithmic system or a neural network that they've trained on images or data that they've collected.

The way that I define generative art is that the artist creates a system that they design and then work with. And there is automation embedded in this process, but there's also intent and creativity and craft in the process of building out the parameters, the set of constraints, the conceptual framework that generates the work. [Then there is] randomness. When you're building a more compact algorithmic program it's the kind of work that a Vera Molnar would have done.

Without the insertion of randomness, you would know all of the outputs in advance. (Julia Kaganskiy)

So previously, when Molnar was working in an analog fashion, she would use dice or find telephone numbers from a phone book to introduce that randomness manually. But then, when she got access to computers, it was kind of the perfect instrument to introduce this randomness through the pseudo random number generator. And I think with more advanced deep learning systems, what you have is just a far more layered, hyperdimensional, space of parameters and possibilities.

Fundamentally, there are some kind of building blocks that you can use to understand the more complex processes by looking at the simple ones.

CR: The show is about the art of systems. Building generative systems is the crux of the show for me!

SC: It was important to me mainly because it opens up a much richer conversation about process. When every work comes from an artist-built system, you’re not just looking at outputs, you’re looking at different ways of thinking: how people write rules, choose datasets, structure randomness, decide what to keep or discard.

AR: It also places the works into the lineage of systems art and conceptual art all of which are about following rules and using those rules as a material in themselves.

When you build your own system, you can trace every decision back to a human hand or a line of thought so that although things might appear automatic or machine produced, they are really not. (Anna Ridler)

SS: We all benefit from compounded efforts so I’m wary of saying any system is truly our own, but building a system that is you, that doesn’t exist without your authorship is an amazing thing to experience. It’s an opportunity to see how your own mind path-finds and problem solves and that’s a wonderful and terrifying thing to do.

Being a painter my whole life and reverse engineering and organizing poems, sculptures, drawings, paintings, brushtrokes, and the participation of those around me into nodes, wires, math expressions, rules, steps, and file structures was an opportunity to get to know myself and see how much of my own humanity can live in “a system” rather than just what it will produce.

The more of myself I extracted, the more new software or layers between software was created, it made me appreciate infrastructure in connection to passion, knowledge bases, organizations, cities; not as abstractions but as collective projects between people. (Sam Spratt)

I didn’t spend much time thinking about these things when I was just painting, and unknowingly it was what I was drawn to in exploring how to expand my toolset.

LJ: How important is it to you that Toledo Museum of Art, a prominent institution with an historic collection, has allotted space, time and substantial resources to a digital art exhibition?

JK: TMA is an encyclopedic museum that has given over gallery space and a lot of time and resources to “Infinite Images”, probably the most ambitious digital art exhibition that TMA has done so far. And I think it's really important to see this work treated with the same amount of care and attention to detail as the Rubens hanging down the hall. And to see this kind of work contextualized within an institution that spans, I think, 4,000 years of human cultural history. For me, that's one of the things that makes this exhibition really special and very different from exhibitions that I've had the opportunity to curate in the past. I hope to see more encyclopedic museums dedicating space to things like this.

Emily Xie: It matters a lot. Putting generative systems in dialogue with 4,000 years of making reframes them from technological novelty to continuity. You see lineages in dialogue with one another.

An encyclopedic museum offers context, conservation rigor, and a broad audience. That combination invites deeper questions around the medium and how these works converse with art history rather than orbiting just digital art culture alone.

CR: I deeply believe that this form of emerging work, “the art of algorithms”, needs to have its own new institutions and it needs to be in institutions like the TMA as well. We need breadth and focus and we also need the context of all of art history. If we think of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, we have a new institution imagined in 1929 specifically for this new art and of course the kind of art in MOMA is also in every encyclopedic institution in the world.

Museums like TMA are exciting because they focus on collecting contemporary art and have been doing that for over 100 years. Contemporary art, 100 years later, is art history. This is an inspired way to build a collection. (Casey Reas)

SC: It’s important because it places digital and generative work in direct continuity with a much longer art history, rather than treating it as a side experiment. It also forces a different kind of accountability: institutions suddenly have to think about conservation, infrastructure, energy, and how to keep these systems alive in 10 to 20 years, which is crucial if this is going to be more than a hype cycle.

AR: I’m very interested in making connections across different points in history, both in my own practice and in our collaborations, where we often draw on moments from the past. Showing this work in a museum like Toledo, with such a deep and encyclopaedic collection, makes those connections more explicit and situates digital art within a much broader cultural lineage. I’ve been thinking a lot about “Wunderkabinets” and early collections — these attempts to categorise and organise the world according to what their makers found compelling — and about the curatorial systems that shape them.

Wunderkabinets were fundamentally systems for organising knowledge but in a weird and esoteric way, which is what I find most interesting about making digital art. Exhibiting these works in a place like Toledo makes those parallels visible, showing how methods of classification and collection have evolved but the underlying questions and idiosyncrasies remain: How do we understand the world? What do we choose to preserve or display? Who gets to do this?

SS: The living record is always being written in real time by passionate people who want others to see beauty in something that has not yet had enough time to be canonized. Canonization doesn’t happen without passionate people who bleed to give artwork the motility and security to be remembered. The museum is a beautiful building. I feel very fortunate to have exhibited [there], but “it” [did not give] over gallery space and resources. People who believe did, and the people who believe are the institution. The reputational risk and reward [in putting on this exhibition] all rested on very human shoulders.

LJ: How does it help a digital artist to work with a curator on a physical gallery exhibition such as “Infinite Images”?

JK: I do think that for artists who are used to working digitally primarily, there is something really important about translating that work into a physical space because it is a process that maybe draws on a different kind of skill set and knowledge base than they're used to working with. Suddenly from a two-dimensional screen, you're working in a three-dimensional space.

You have to think architecturally. You have to think of the visitor experience. If you're doing something for a museum or a gallery space, you have to think of accessibility, of catering to different kinds of audiences than just yourself. (Julia Kaganskiy)

And I also think that a lot of artists who maybe don't have that experience really benefit from collaborating with curators or exhibition designers. I mean, that's certainly been my observation. I've worked with some artists who are primarily digital, but maybe have some training in architecture. And they are very adept at thinking spatially. But other artists might just reach for what they've seen before, rather than thinking site-specifically or about the particular context that they're working in.

CR: Curators and exhibition designers know how to communicate with the public and it’s essential. Each artist is the expert in their own work, but not the expert in the big picture and how to connect with wide audiences. You know that idiom “Can’t See the Forest for the Trees”. As artists, we’re building our own trees and we’re deep into this work, but we can’t see or experience the entire forest.

We need the context of a curator who spends all of their time talking with artists and thinking and writing about that context to create an expansive and resonant exhibition like this. (Casey Reas)

EX: It’s very important—even when the work is digital work displayed in print form, which was in my case. A good curator translates intent into space. Julia Kaganskiy obsessed over color accuracy, paper, and lighting. I was pleased with how the images were displayed, and how they supported how the series was meant to be read. Thinking architecturally mattered a lot for the overall exhibition: wall height, pacing, and arrangement around the room guided people as they grappled with a likely unfamiliar art form. My biggest takeaway was that the curation made the work sharper, more understandable, and more welcoming to different audiences.

SC: It’s super important, especially because not all digital works are meant to stay on screens. For this exhibition we worked closely with Julia to find ways of presenting the pieces so that it’s clear they can, and should, take up physical space in the gallery.

AR: It’s really important. Seeing something in a physical space is very different from seeing it on a screen where you have no control over the size it will occur, how much attention will be paid to it, what else is going on in the background. In a physical exhibition there is so much more scope to create an experience, which in an age where it is easier than ever to create an image, are becoming increasingly important I think for an artwork.

SS: Julia gave me a gift I believe a great curator can provide for an artist. I understand my own creations far more than I did before meeting her. She looked where others might not within my practice to understand Luci, opened a well of knowledge and decision-making into what goes into every placement, and had the grace to generously communicate my place within historical context.

Well-placed resources for curators with a deep well of knowledge and history, like [Julia Kaganskiy], do far more than sequence or select artwork: an ecosystem of artists, collectors, institutions, platforms, would greatly benefit from investing in curators who can help each element know itself better. (Sam Spratt)

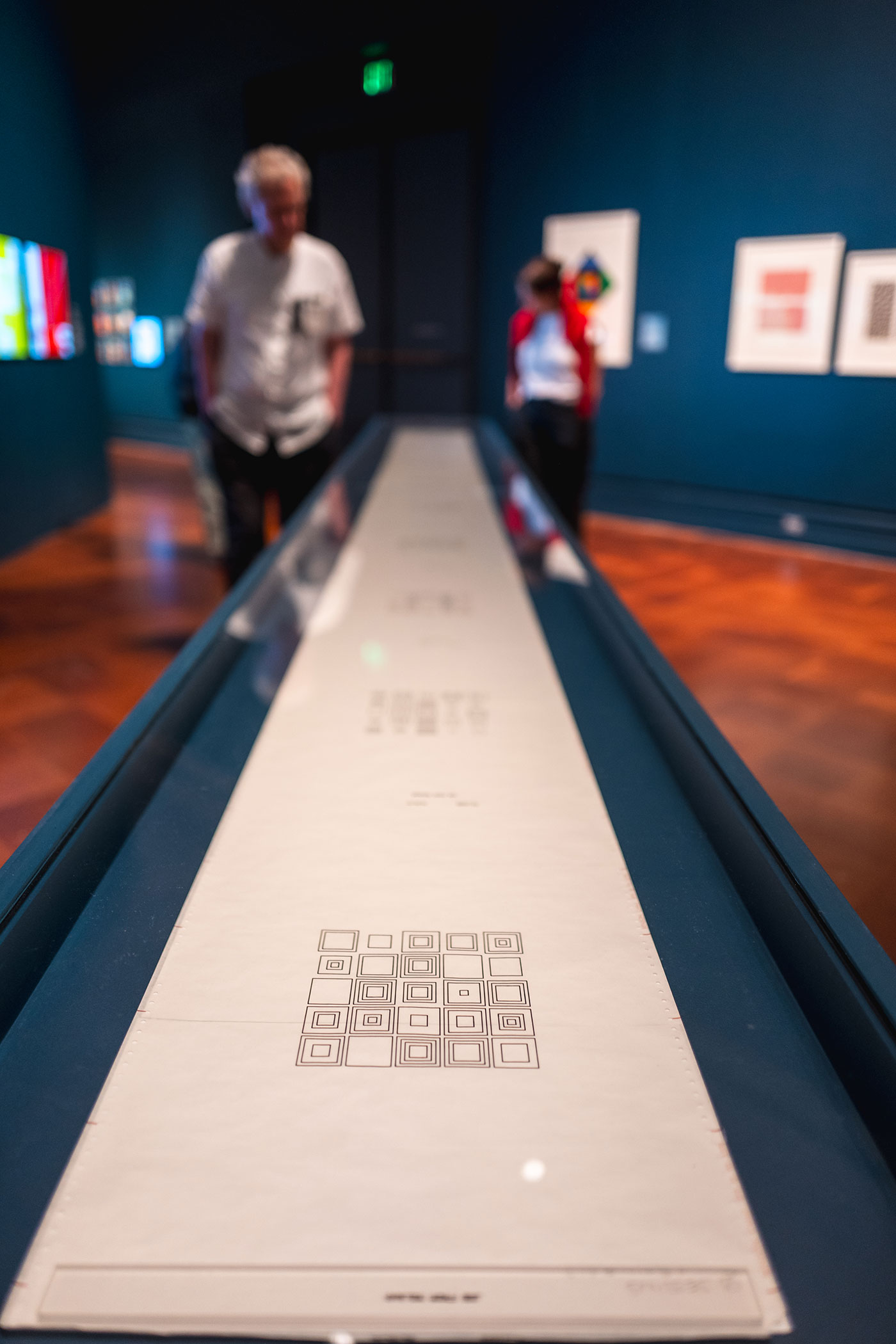

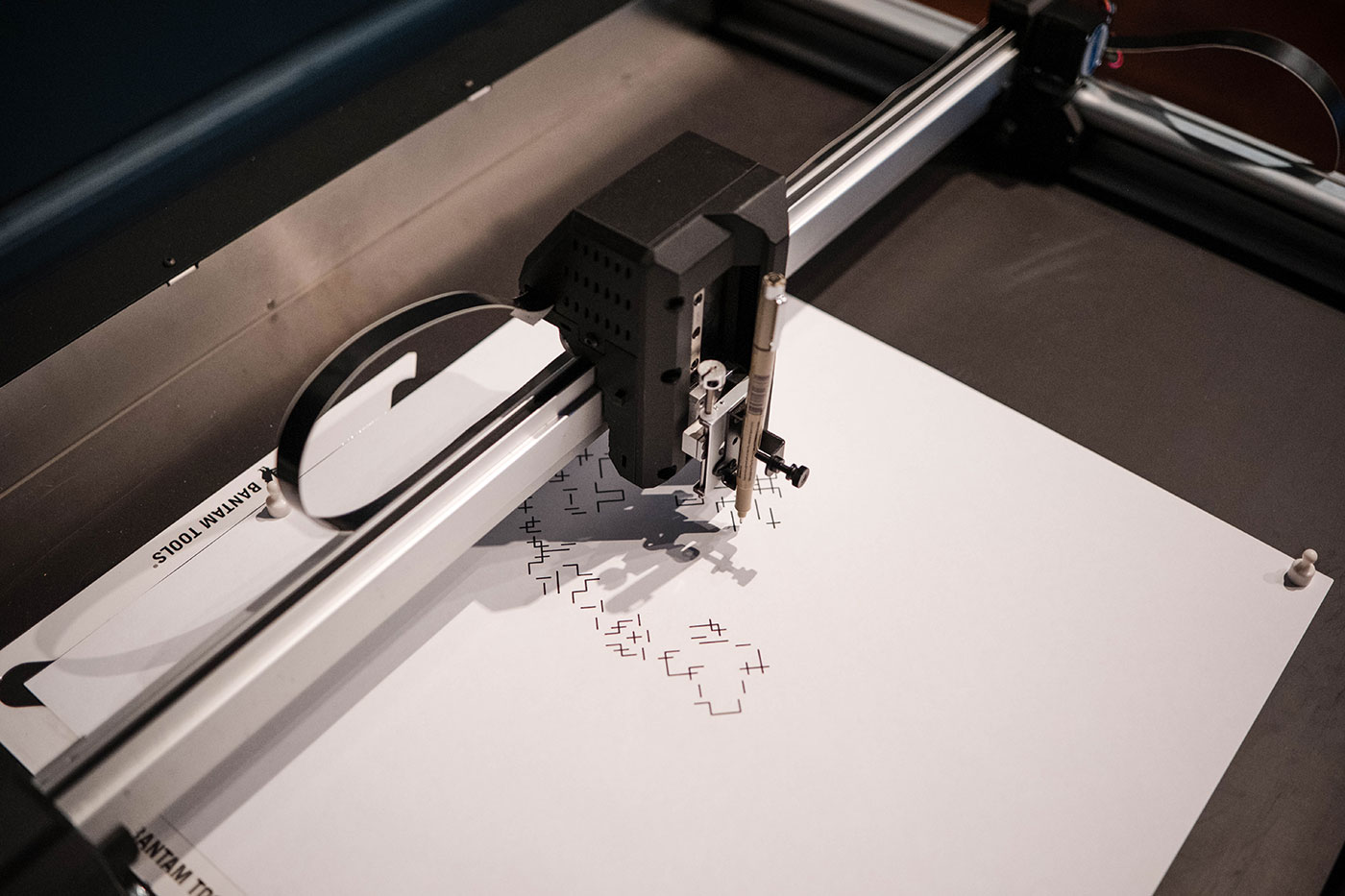

LJ: What was it like witnessing other people experience the work on site, including the interactive elements such as live plotting of Autoglyphs for supporters of the museum and the stationn for visitors to interact with Tyler Hobbs's QQL algorithm?

JK: One of the best things about seeing the show in person and particularly the interactive works is how popular they are with kids. An artist in the show who brought his kids to the exhibition—they're somewhere between eight and 12—was saying that the show was such a hit with them and also with him because of the way that interactive pieces were peppered throughout the exhibition. So the pacing really worked for him and his kids because the next interactive station was just a few works away. That it was enough of a hook to keep their attention on the stuff that was static, to keep them engaged. These moments really helped bring people, especially kids, into the work.

SS: I felt myself and the other artists involved all [examining] the same part of consciousness, all with our own belief-systems, but all trying to be a relay. That somewhere between you and the thing you know there is something you don’t.

In the space between, I found this genealogical tree of a bunch of people across time and space tinkering with computers to reveal nature. (Sam Spratt)

I found it to be a connective experience to gather people in my world of Luci and introduce them to my work and process; not just in my isolated fiefdom, but in the context of the 80ish years that the exhibition holds; of the giants I am building atop and around, and to the thousands of years that preceded us. At first it all feels new and like it doesn’t belong. But you come closer and something changes.

LJ: As we approach the fifth anniversary of the launch of Art Blocks on 27 November 2020, how do you see the future of generative art on the blockchain? What is the state of innovation in the field?

JK: One of the things that that Art Blocks did really well was to consider the blockchain as a native medium and to think about how it can facilitate a new type of experience of generative art, a new type of relationship between artists and algorithm, a new type of relationship between artist and collector, between collector and audience.

That experimentation with what does it mean to create generative art on the blockchain specifically—and what it can enable that feels new and like it's advancing the conversation—that is what excites me the most about what Art Blocks has done and about what the future can hold.

I feel there was a lot more innovation happening in 2021, 2022, and that it's maybe petered down a little bit. So I would love to see the infusion of more experimentation into the scene. (Julia Kaganskiy)

SS: I think there is a very specific era of generative art that is its own, and is with great intention being preserved as something of a time capsule. But the foundation laid is for synthesis: art that doesn’t fetishize the machine or worship the hand as the space between each tool, medium, mode of expression shrinks, and the stretched definition goops on into something else entirely.

CR: The idea of generative art as distilled by Art Blocks has infinite possibilities that can be explored over hundreds of years into the future, similar to how painting on canvas is an endless exploration of images, meaning, and emotion. We’ve been through a decisive moment and we’re still very much at the very beginning. Art and code goes back to the 1960s and this creative practice and theory was defined at that time, but the surge of energy and activity starting in fall 2020 was unprecedented within this 60-year period and I think it changed everything. People are exploring in all directions, but the core of it is the most fertile ground.

Julia Kaganskiy is a curator and cultural strategist working across art, science, and technology. She is passionate about interdisciplinary collaboration, developing new cultural models, and re-imagining cultural institutions as inclusive spaces for artistic experimentation. Since starting her career in 2008, she has been recognized as a leading voice in art and technology and helped launch several groundbreaking programs in the field, including The Creators Project, @vice, and NEW INC, @newinc, @newmuseum.

Kaganskiy’s curatorial practice explores the potential of art as a key interlocutor of emerging science and technology. Until recently, she served as Curator-at-Large at @las_artfoundation in Berlin, where she oversaw the Interspecies Future research stream and co-edited the book “Interspecies Future: A Primer” (Distanz, 2024), @interspecieslibrary. As an independent curator, she has worked with 180 Strand, @1800.studios (London, UK), Matadero Madrid, @mataderomadrid (Madrid, ES), Espacio Fondación Telefónica, @espacioftef (Madrid, ES), Borusan Contemporary, @borusancontemporary (Istanbul, TY), Science Gallery, @scigallerydub (Dublin, IE), Barbican Centre (London, UK), Eyebeam (New York, US), Mana Contemporary, @manacontemporary (Jersey City, US), Feral File, @feralfile, and many others.

Sofia Crespo is an Argentine artist based in Lisbon, Portugal, whose practice explores the convergence of artificial intelligence and biological systems. Working as part of the artistic duo Entangled Others with Norwegian artist Feileacan Kirkbride McCormick, she investigates how organic life and artificial mechanisms simulate and evolve each other. Her work has been exhibited globally at institutions including the Victoria & Albert Museum and in Times Square. In 2022, Entangled Others’ work Swim was acquired by the Buffalo AKG Art Museum for its permanent collection. Crespo’s contributions to the field have been recognized by the German Informatics Society with its AI Newcomer Award.

Anna Ridler is an artist who works with systems of knowledge and how technologies are created in order to better understand the world. She is particularly interested in the natural world. Her process often involves working with collections of information or data, particularly datasets. Her work has been exhibited at cultural institutions worldwide including Times Square, the Barbican Centre, the Centre Pompidou, HeK (House of Electronic Arts, Basel), the Photographers’ Gallery, ZKM (Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe), the Ars Electronica Center, and the Victoria & Albert Museum. She received an honorary mention in the 2019 Ars Electronica Golden Nica awards for the category AI and Life Art.

Casey Reas is an artist and professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he codirects Social Software. Reas’s software, prints, and installations have been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions. His work is included in private and public collections including the Centre Pompidou, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. He is the cofounder of Feral File (2020), Processing (2001), and the Processing Foundation (2012) and the author of books including Compressed Cinema (2023) and Form + Code in Design, Art, and Architecture (2010). He holds an MA in Media Arts and Sciences from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Sam Spratt creates from rupture—the pursuit of redemption through solidity, to chart a path forward from past missteps. His current body of work, Luci, a series of digital paintings, follows the infinite story of pilgrimage and serves as a refracted self-portrait of the artist. Each piece is a confession, a conversation, and a joke at our own expense. Through the process of palingenesis, this episodic body of work serves as guides and warnings for the atomized individual exiting dissociation and attempting to connect, grow, and thrive in an escalating network. Sam lives in the United States of America and works out of his studio in New York City. His artwork has found homes in games, films, music, books, comics, magazines, theater, and most creative industries.

Emily Xie is a visual artist who merges code with craft to create generative artworks rich in pattern, symbolism, and abstraction. She holds a BA in the History of Art and Architecture and an MS in Computational Science and Engineering from Harvard University. Recently, she has exhibited at the Untitled Art Fair, the United Nations Headquarters, Singapore ArtScience Museum, Kunsthalle Zürich, Unit London, the Armory Show, and Bright Moments. At TMA, she expands her generative systems into glass and an immersive experience.

Louis Jebb is Managing Editor at Right Click Save.