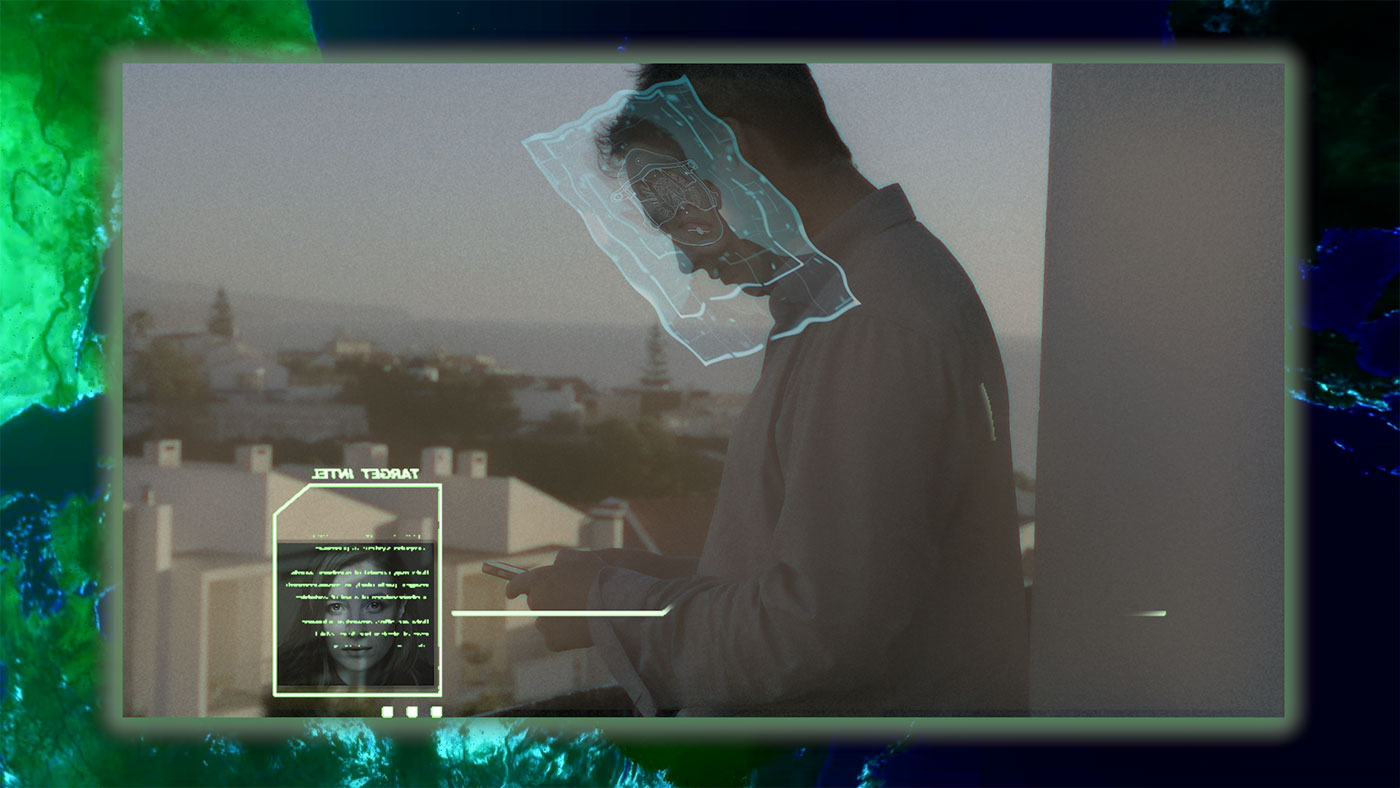

In the process, The Sphere has developed a form of what has become known as protocol art, where the rules and systems developed are as important as, or more important than, the work itself.

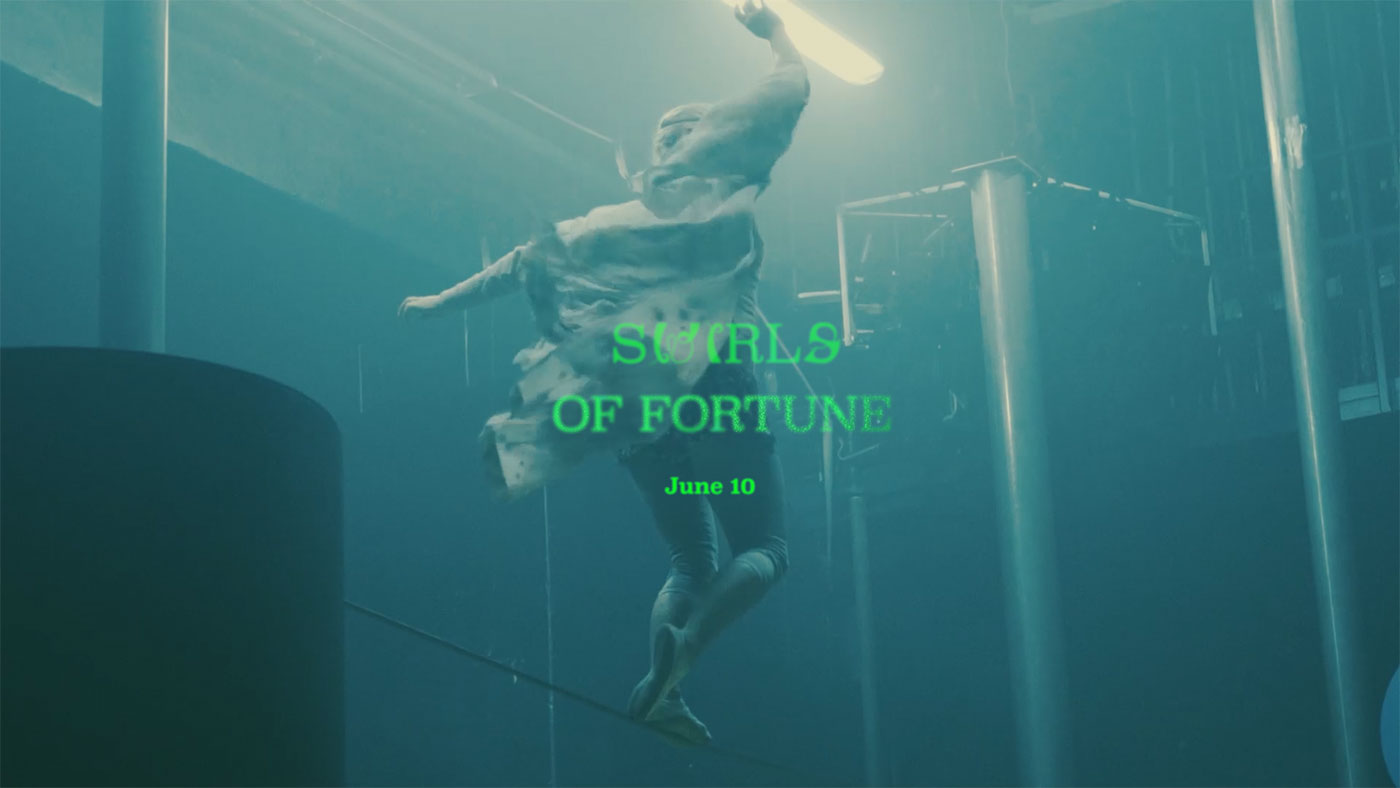

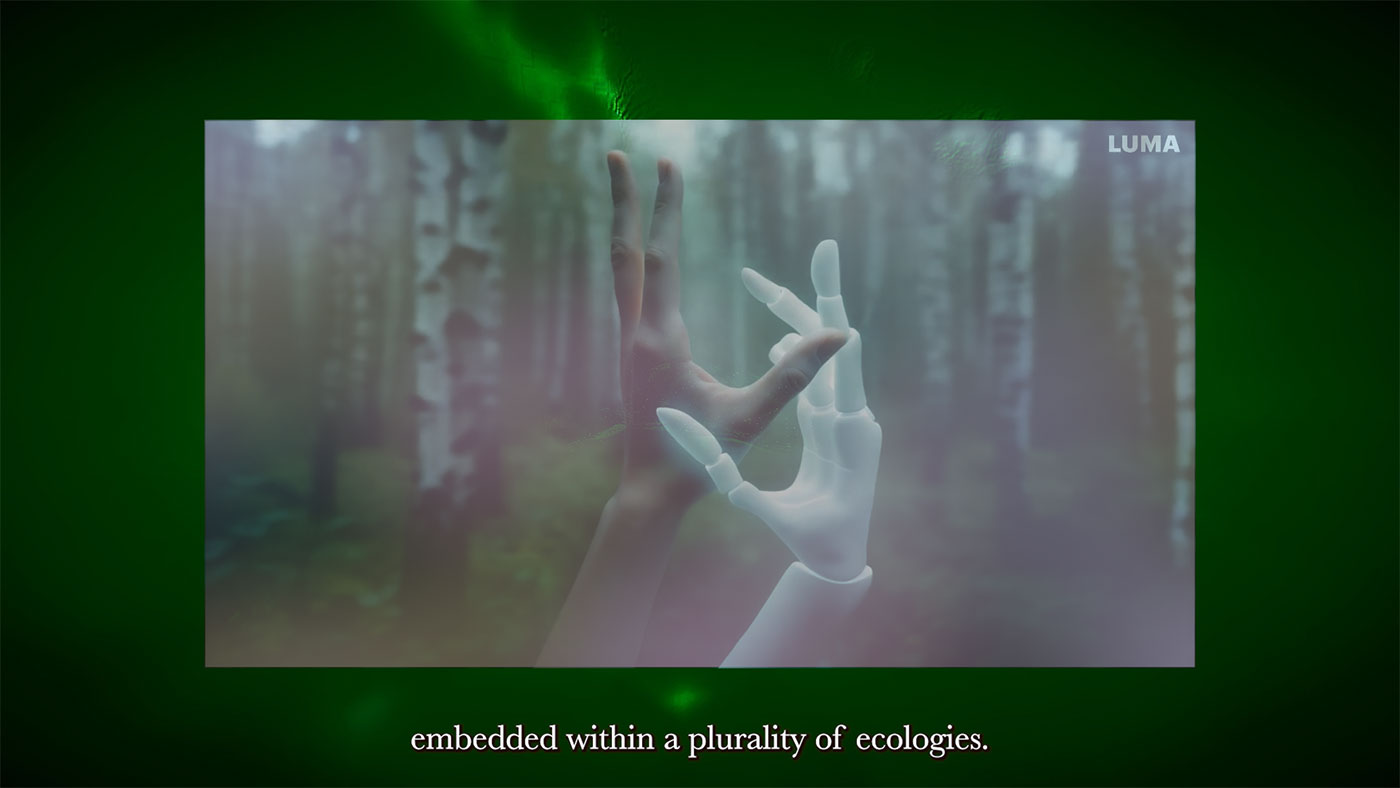

At its center are two figures: Swirl, a trickster “goddexx”, rendered as a spiral entity whose body vibrates to the words it speaks; and the Network Clown, embodied by Vollhardt herself, a contemporary descendent of the commedia dell’arte character Pierrot, the melancholic white-faced fool perpetually out of sync with the mechanical world.

Around them move circus clowns and computer-game-like non-playing characters in what Bordeleau describes as “productive tension” between “automation and agency, programmed behavior and emergent improvisation”.

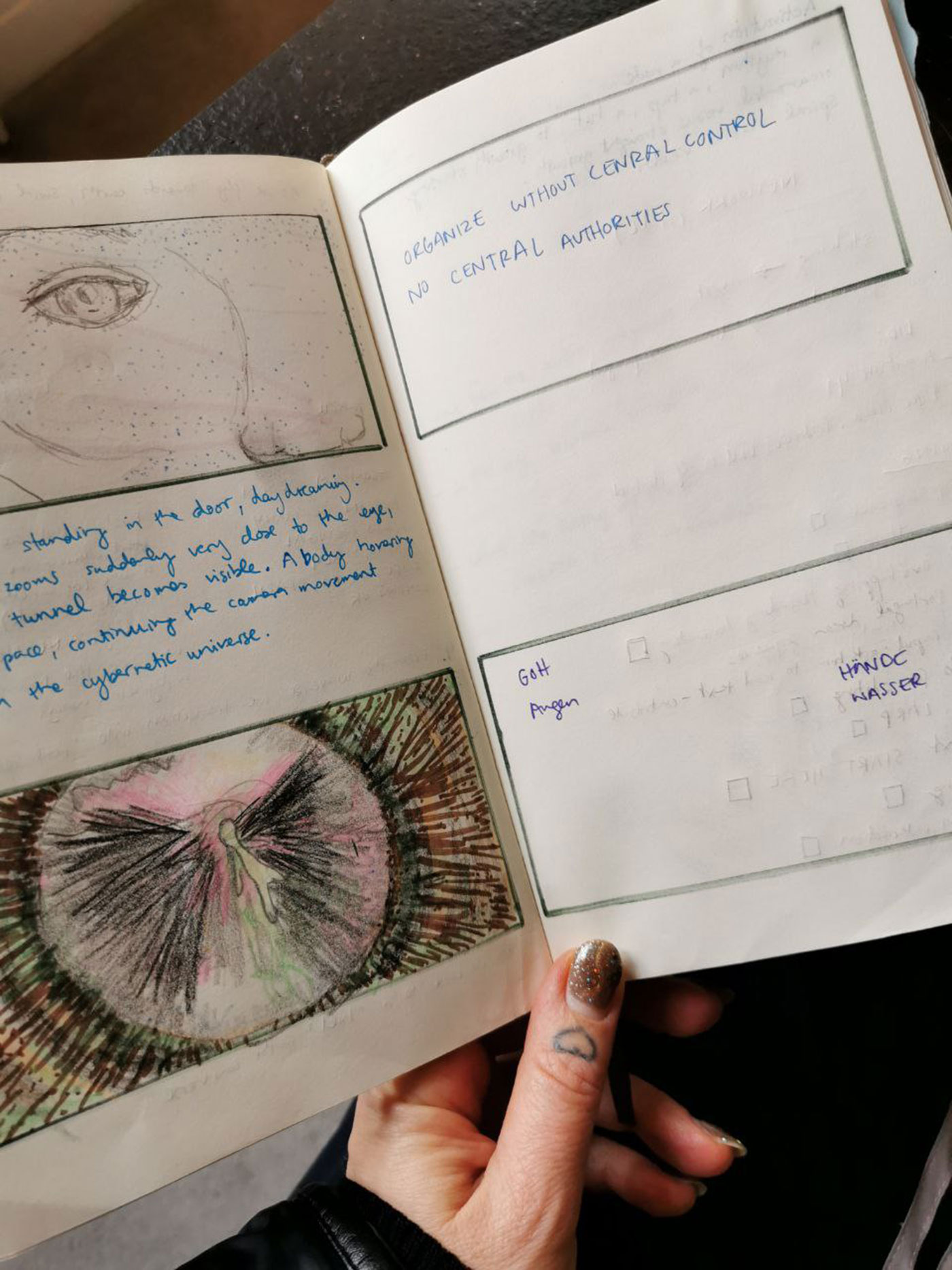

We wanted to collect our story, to create a decentralized memory of our own development; of having produced games and mechanisms that involve the creation of governance mechanisms and sets of protocols, or rules.

The film is intended as an artefact, an origin story that would connect all the different threads and all the different languages that we speak to in the Sphere.

There are “degen” aesthetics in the film, memes and expressions that are infected by the whole “degen” culture of high-risk speculation in crypto. The Sphere is a part of this ecosystem, even though it does not develop protocols for speculation with currency and has never participated in NFT hype.

What interested us was that they are essentially doing protocol design for democracy itself: asking how you build rules that make collective decision-making more plural and more resilient. Which is exactly what we were trying to do for live art.

A protocol defines a frame, a rhythm, a set of allowable moves, but each performance is a negotiation in real time between the score, the bodies present, and the situation. Protocol art, for me, operates in a similar way: it sets conditions, but the actual “work” only appears at the moment of execution.

Protocol art prioritizes dynamic systems over fixed objects. Rather than producing fixed objects, protocol art composes dynamic systems: situations, scripts, and roles that did not exist before.

And then when I got into the real “art world”, I didn’t really understand it. It just felt ungraspable, and very impersonal; where contemporary art was an overwhelmingly static experience in a world where a few figures in power got to decide what an artist’s legacy should be.

I had had the good fortune to work as a camera operator, guided by the cinematographer Juergen Juerges, on the final weeks of filming for DAU (2014), an impossibly ambitious, now near-mythic, immersive work set in an alternative, Big Brother-like, Orwellian world.

One of the surprising effects that we have observed was that circus artists have a loose attachment to their artwork. And that has to do with circus art as a discipline with a traditional craft, where they reiterate the classics constantly.

At The Sphere we wanted to create a system in which artists can decide what they want to preserve from their art, so that it stays alive and doesn't become something static to be locked away in a museum, and we wanted to give that into the hands of a community.

Lene Vollhardt is a German-American performance and moving-image artist working on the relationship between bodies and code. Through film, choreography, and protocol design, she explores how digital infrastructures inscribe themselves into flesh, and how embodied practices can rewrite those scripts. Her work moves between plural voice, fractured timelines, and governance-as-choreography, treating attention as material and healing as transfer rather than transaction. Vollhardt co-directs The Sphere, a Web3-based arts ecosystem developing infrastructures for live art and cultural memory. She is a PhD candidate and Research Fellow at the Law & Theory Lab, University of Westminster, where Swirls of Fortune anchors her doctoral research. She trained at the Staatliche Hochschule für Gestaltung Karlsruhe (HfG/ZKM) under Isaac Julien and is a graduate of the Royal Academy of Arts Schools, London. Her work has been supported by Serpentine Arts Technologies, RadicalxChange, Chisenhale Dance Space, and the Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes, and presented internationally at venues including the Royal Academy of Arts, Sharjah Art Foundation, Vitra Museum, and Berlin Art Week.

Louis Jebb is Managing Editor at Right Click Save.