The New Museum, New York, reopens on March 21, 2026, after a two-year $82 million rebuilding program that has doubled the contemporary art museum’s exhibition capacity. The enlarged institution’s first thematic exhibition, “New Humans | Memories of the Future”, exploring artists’ concern with what it means to be human in the face of technological change, is curated by Massimiliano Gioni, the Edlis Neeson Artistic Director at the museum.

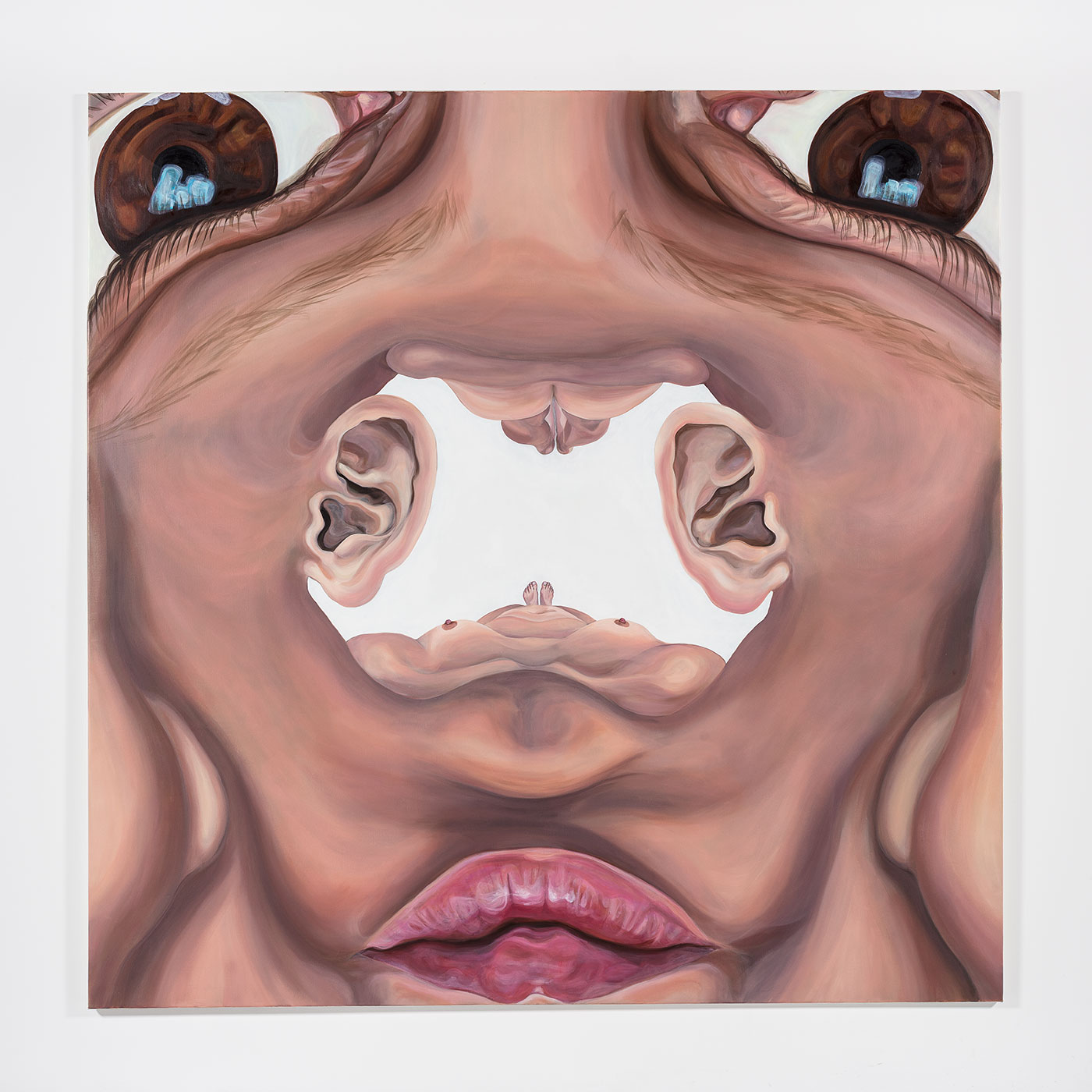

A number of artists, including Julien Creuzet, Jaider Esbell, Jana Euler, Christopher Kulendran Thomas, Tau Lewis, and Portia Zvavahera, will show work reimagining what the museum describes in a statement as “speculative universes in which the definitions of the human are constantly renegotiated with both the animal and the natural world”.

We also wanted to make sure that [in] doubling the [exhibition] space, we remained an extremely flexible, experimental, nimble institution. That's still the case. So we are not renouncing our ethos or our DNA but we have many opportunities to do more things or different things.

The second aspect is a house specialty of the New Museum: [giving] the first solo shows to artists in New York [across] a very wide spectrum [from] very young artists [to] more established ones like Judy Chicago [in 2023-24] or Theaster Gates [in 2024]; artists who, for differing reasons, had not [previously] received the recognition they deserve.

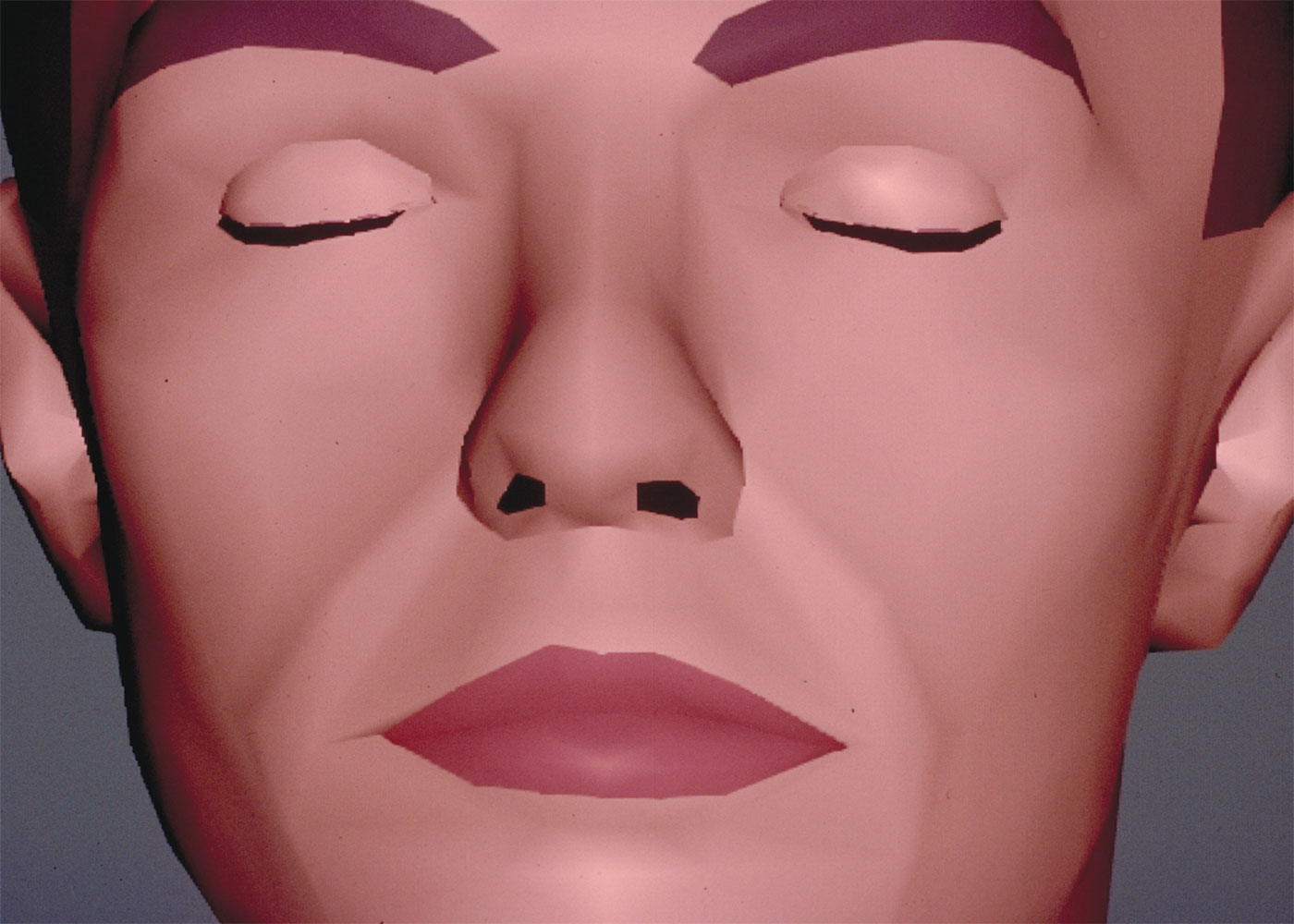

This is the case in point with “New Humans”. It is an exhibition about art and technology and more broadly about how definitions of the human shift under the impact of new technologies.

Education is also very present in our community, in our neighborhood. We give classes in the [public] housing in the neighborhood of the Lower East Side. With New Inc and Rhizome we are present locally, internationally and digitally.

[One hundred years ago] humans were confronted with similar technological revolutions. [The show makes the point] that the word robot, which now takes on so much space in our imagination, was created in the 1920 play Rossum’s Universal Robots, by Karel Čapek.

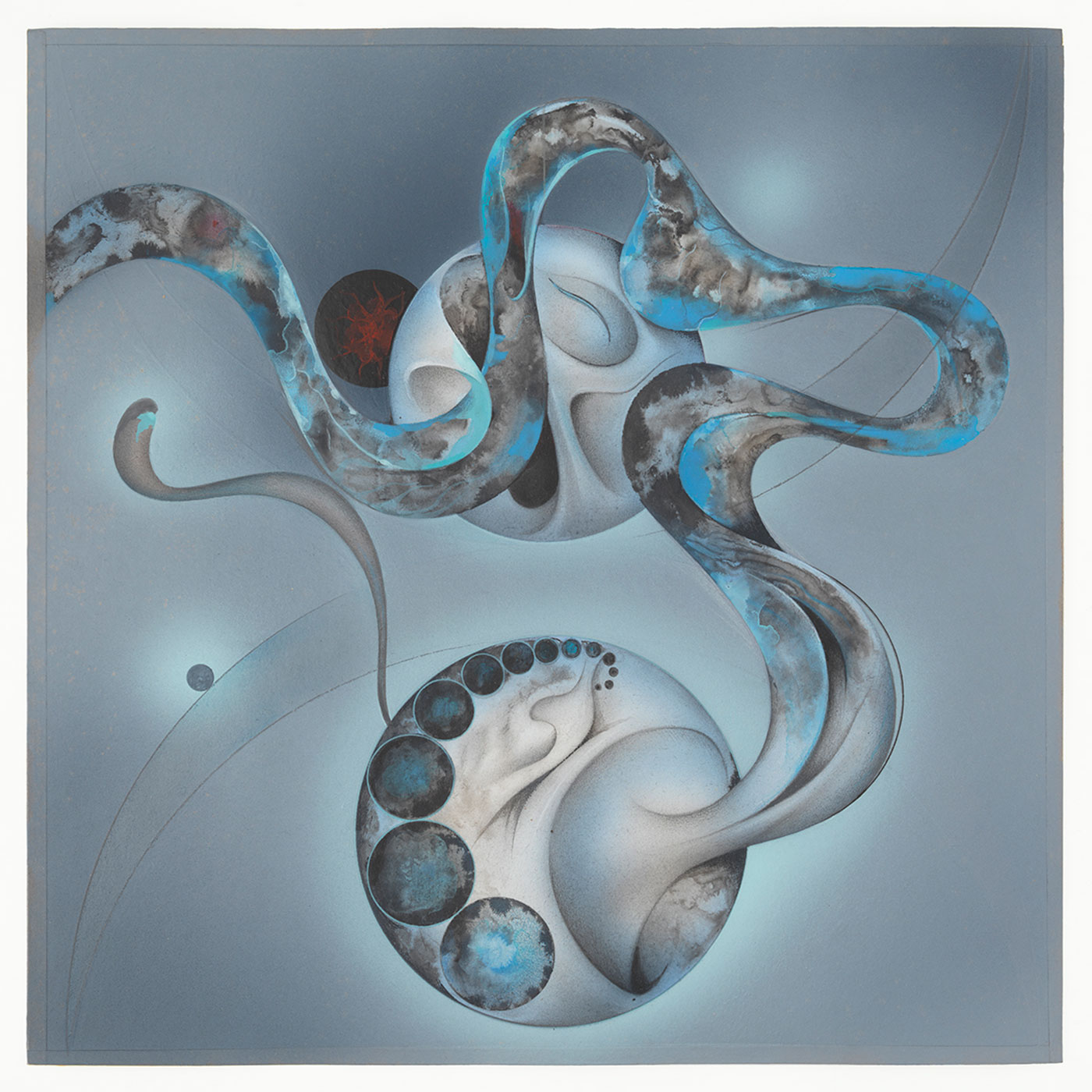

It’s probably a misplaced desire, but it’s one that is also very close to the act of making art.

I hope as the exhibition gets deeper and denser some of these questions will appear to be even more fundamental than the question of technology; around the myth and the fantasy of giving life.

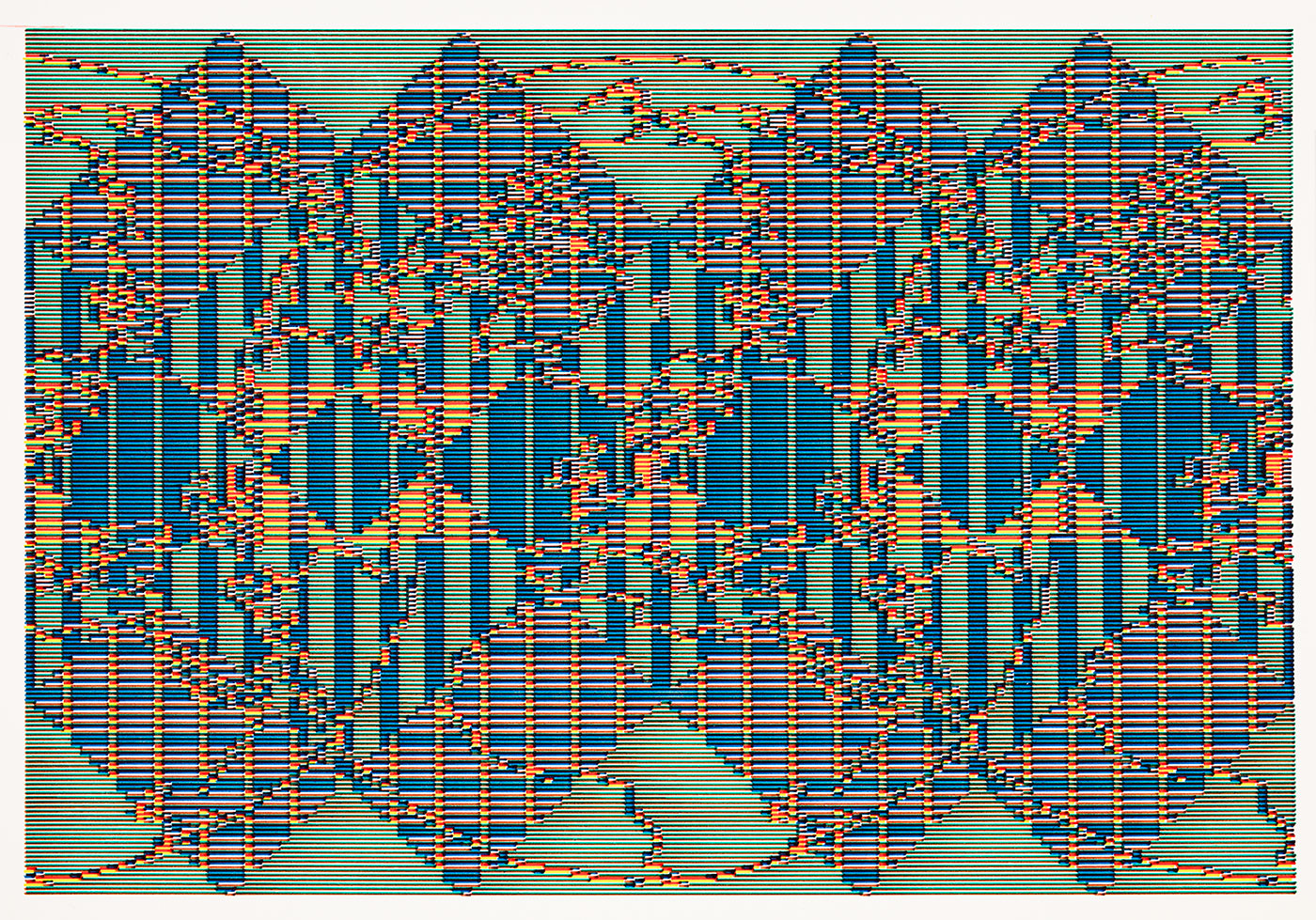

And the irony, which is typical of Hito’s work — she’s an artist who embraces new technology and the piece uses new technology — [is that] she reveals the very physical human and infrastructure that supports new technologies.

MG: The show takes as a starting point a quotation from Karel Čapek, in Ross Universal Robots, [where a] character says “there is nothing stranger to humans than their own image” and Čapek’s play is all about the uncanny valley and the strangeness of the encounter with artificial life.

One of the assumptions of the show is that in moments of existential threat — and I borrow this idea from Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, the anthropologist — we go back to myth.

Maybe [the show is] less about the technology and more about the human and the need for the human to invent stories to deal with these existential threats.

If you define the human in relation to the machine at one end, you’re defining the human in relation to the subhuman, or the animal, at the other. And that definition is loaded with consequences.

We tried to make a show that feels grand and complicated but in some cases also uses very modest materials.

Though many are still struggling with attendance, I think museums are places of encounter, places of discovery, and learning. We seem to be necessary and that is, I think, encouraging and exciting.

Massimiliano Gioni is the Edlis Neeson Artistic Director at the New Museum, New York. He leads the museum’s curatorial team and is responsible for the exhibition program. As a member of the senior management team, he works closely with the Director and has broad responsibilities for museum-wide planning.

Gioni joined the New Museum in 2006 as Director of Special Exhibitions, and was appointed Artistic Director in 2014. At the museum, he has curated exhibitions of artists including John Akomfrah, Pawel Althamer, Ed Atkins, Lynda Benglis, Judy Chicago, Tacita Dean, Nicole Eisenman, Urs Fischer, Theaster Gates, Hans Haacke, Camille Henrot, Carsten Höller, Kahlil Joseph, Ragnar Kjartansson, Kapwani Kiwanga, Sarah Lucas, Gustav Metzger, Marta Minujin, Chris Ofili, Raymond Pettibon, Carol Rama, Faith Ringgold, Pipilotti Rist, Anri Sala, Peter Saul, Nari Ward, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, among others. He has organized major group shows including “After Nature” (2008); “Ostalgia” (2011); “Here and Elsewhere” (2014); “The Keeper” (2016); and “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” (2021), an exhibition originally conceived by Okwui Enwezor and realized in collaboration with Naomi Beckwith, Glenn Ligon, and Mark Nash. Gioni established the New Museum Triennial as The Generational Triennial: Younger Than Jesus in 2009 with Lauren Cornell and Laura Hoptman.

Gioni’s international exhibitions include Manifesta 5 (Donostia-San Sebastian, Spain, 2004); Berlin Biennale (2006); 10th Gwangju Biennale (2010); the 55th Venice Biennale (2013); and The Great Mother (Milan Expo at Palazzo Reale, 2015) and The Restless Earth (Milan Triennale, 2017), both with the Trussardi Foundation.Gioni’s international exhibitions include Manifesta 5 (Donostia-San Sebastian, Spain, 2004); Berlin Biennale (2006); 10th Gwangju Biennale (2010); the 55th Venice Biennale (2013); and The Great Mother (Milan Expo at Palazzo Reale, 2015) and The Restless Earth (Milan Triennale, 2017), both with the Trussardi Foundation.

Louis Jebb is Managing Editor at Right Click Save.