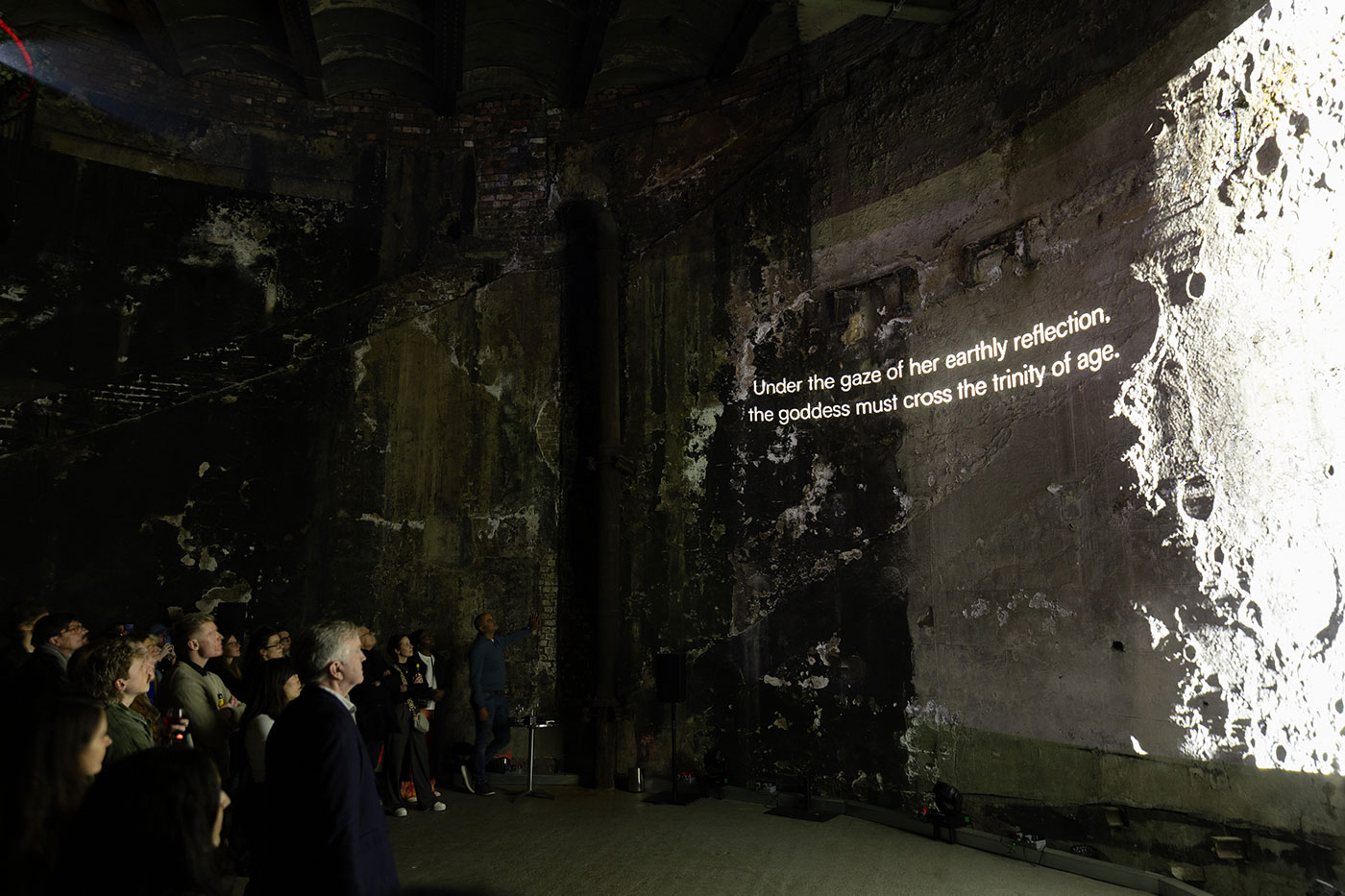

In London, the film was projected onto the walls of the massive subterranean Brunel Shaft, which had been erected in 1825 to initiate work on the Thames Tunnel, the world’s first underwater tunnel, by the father-and-son engineers Marc and Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

The figures, Bourdin says, “explore how ancestral archetypes can be reborn through contemporary means, and how the universal can emerge from diversity, hybridity, and reinvention”.

In essence, I wanted to capture the dialogue between the static and the breathing, the archaic and the present, where sculpture extends beyond matter and enters the realm of lived experience.

From the outset, I was clear that if I made a film, it would not be documentation. I wanted to build a cinematic narrative around this figure developed by Hermine. A goddess coming to earth, and her passage through the three archetypal stages of a woman’s life: Maiden, Mother, and Crone.

I was looking for a language capable of holding contradiction: something timeless yet radically modern.

Ultimately, black and white was not a stylistic overlay. It was the condition that allowed the film to exist in a space of clarity, austerity, and intensity, where form steps back just enough for presence, movement, and human fragility to come forward.

It recalls Constantin Brancusi’s assertion that plaster is “the material of dreams”, and it nods to the centenary of Surrealism, evoking Cocteau’s Le Sang d’un Poète, in which Lee Miller is transformed into a plaster figure that comes to life.

From this process emerge figures that reactivate the primal power of the Venuses: bodies freed from norms, bearing a freedom that spans millennia.

That approach aligned very naturally with my own desire to work with presence rather than representation.

Working with sculpture and choreography was not about combining disciplines. It was about learning how to step back, and letting different forms of embodied knowledge speak through the camera.

By making the moon a character, it became at once a mirror for the goddess and for the spectator and a reminder of the brevity of our own earthly passage.

We chose to begin not with the Maiden, but with the often overlooked, older woman who carries wisdom. This allowed us to embrace a non-linear narrative, in dialogue with Surrealist cinema, recalling the works of Maya Deren, Man Ray, and Luis Buñuel.

The music was not added afterwards as an atmosphere; it was woven into the film’s temporal and emotional structure.

It asks for time, attention, and a certain availability from the viewer. In that sense, it may remain a rarer experience, but rarity is not a weakness here; it is part of the work’s meaning.

The images are not simply projected; they inhabit the space. This is exactly the kind of life I want the film to have.

Hermine Bourdin, a French sculptress, investigates the feminine through a nuanced dialogue between memory, the body, and the natural world. Inspired by Palaeolithic and Neolithic art, she engages with the organic and symbolic language of primordial forms, reinterpreting these ancient figures as active, transformative presences within contemporary space. Her work bridges temporalities, allowing the forms of the distant past to resonate in the present, carrying with them a poetic and ritual intensity. Beyond traditional materials, Bourdin extends her practice into the digital realm, employing contemporary technologies to animate, transform, and reimagine these forms, creating a dynamic interplay between the tangible and the virtual, the archaic and the immediate.

Hervé Martin Delpierre is a Paris-based film-maker: a director, producer, and writer, and co-founder of Kiritosu Studio. He explores the intersection of art, technology, and society through documentary cinema. His films are known for their sensory approach to reality, where form becomes reflection — a cinema of perception, gesture, and metamorphosis. His Daft Punk Unchained (2015) — the definitive film on the legendary French duo — sold in over 110 countries and was broadcast in prime time on major networks worldwide. His What the Punk! documentary on Larva Labs and Cryptopunks premiered at Art Basel in Basel in June 2024.

Louis Jebb is Managing Editor at Right Click Save.