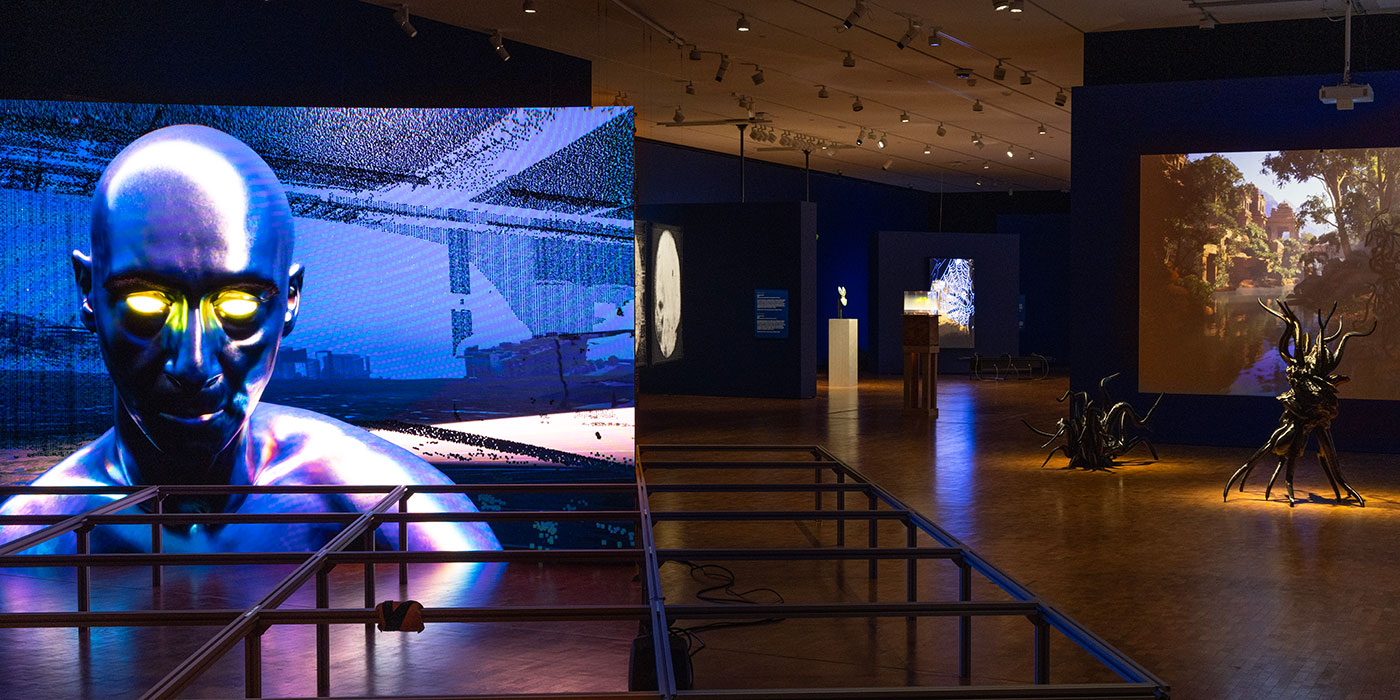

“Almost Unreal”, the 2025 edition of the Munch Triennale, curated by Tominga O’Donnell and Mariam Elnozahy, is at Munch, Oslo, the museum home of the world’s largest collection of works by Edvard Munch (1863–1944), until February 22, 2026.

Elzohany highlights how Forti, a choreographer, had the idea in the 1970s, in dialogue with a physicist, of converting certain dance moves into three-dimensional holographic projections that “allow an illusion of movement, which becomes evident when the viewer moves around the hologram”.

“Recent technological developments enable the creation of simulated, augmented and enhanced realities, which destabilises the idea of truth and veracity. Anything can be faked, so what can you trust?” (Tominga O'Donnell)

It seems to go beyond the real and the unreal into a zone of hyperreality, as a technocultural progression that LiDAR helps to faciliate remarkably.

Lasting fifteen minutes, Bucknell’s work is a critical intervention in contemporary art’s repositioning in, and critique of, the era of big, extractive data. It deserves to be seen more widely. An accompanying video game meanwhile invites interaction.

Škarnulytė tells Right Click Save that her ecologically and cosmically related work often engages with “dead zones” in oceanic and river waters, as a consequence of human pollution and despoliation of natural resources.

With the exhibition sitting in the Munch museum, home to the defining collection of Edvard Munch’s works, it is difficult to overlook the relationship to the expressivity of Norway’s best-known artist.

Bronac Ferran is a writer, curator, and researcher based in London. She has been commissioned to write exhibition reviews and catalogue essays by, among others, LACMA; ZKM, Karlsruhe; the Migros Museum, Zurich; Tate Liverpool, Tate Modern; the Mayor Gallery; Victoria Miro, London; and Studio International. She is a former Senior Research Tutor in Innovation Design Engineering at the RCA and a former Director of Interdisciplinary Arts at Arts Council England.