The following panel discussion was curated by Diane Drubay and presented as part of The Digital Art Mile, founded by Roger Haas and Georg Bak.

Creating classifications and taxonomies that are fluid and open to change is incredibly important for the evolution of digital art. And you don’t simply come up with a term. Creating vocabulary really is dialogue, a back and forth with artists, with institutions, with art critics. (Christiane Paul)

What we’ve adopted at Centre Pompidou, not as an official name, is the notion of variable or unstable media, which reflects the ephemeral and often precarious nature of those media in terms of conservation. (Marcella Lista)

Centre%20Pompidoun%20MNAM-CCI%2C%20HELENE%20MAURI%20(1).jpg)

It’s incredibly important when acquiring works for the collection that I talk with an artist about how they want their work to be understood, and what labels they do and do not want — it’s not one model fits all. (Melanie Lenz)

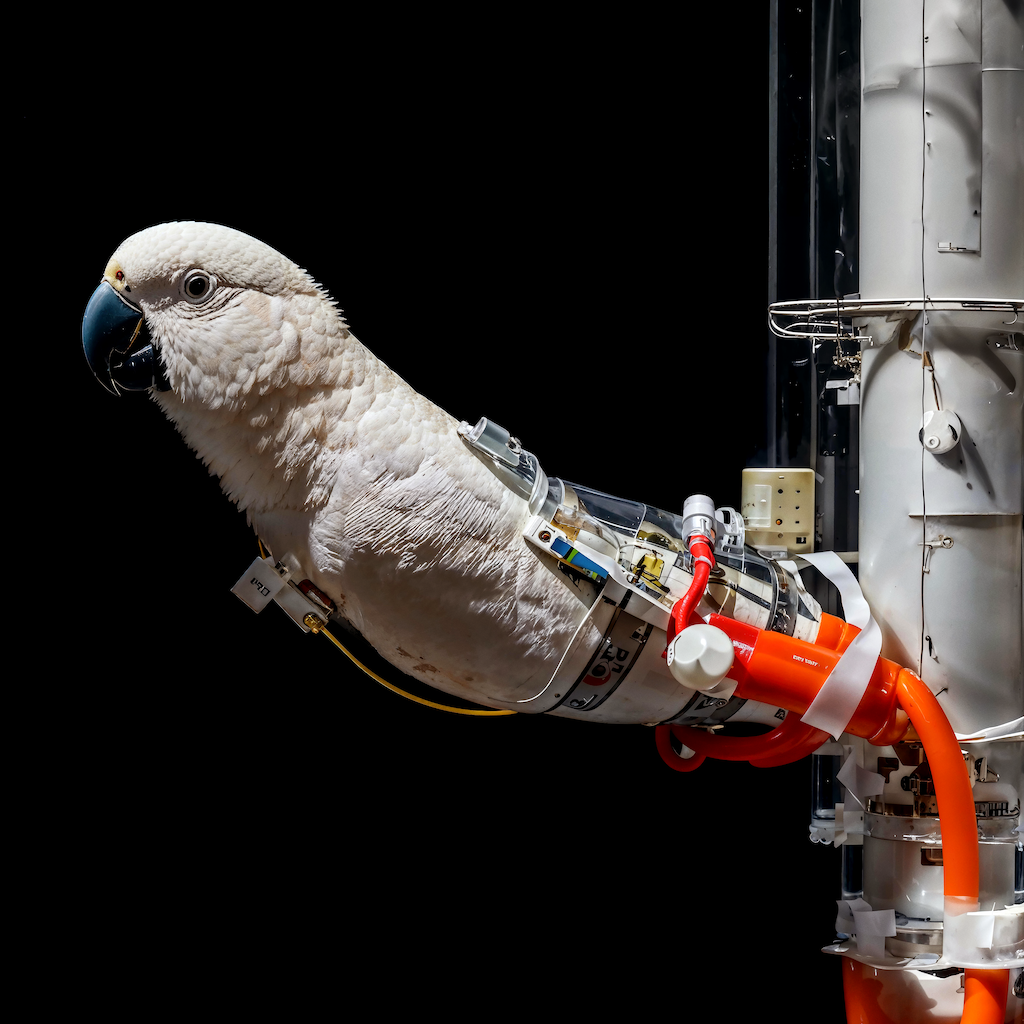

When I was younger, I tried to bury the fact that I had worked with photography for years — people called me a photographer, but I always rejected that label and made a point of trying to get people to forget it. Now that I’m known for my synthetic photography, people say to me, “you’re undermining the value of real photography; you should learn something about real photography,” which is amusing. (Kevin Abosch)

I want to be very careful with judgements here — creative expression in any way is fantastic. That doesn’t mean that museums need to collect all of it. There are distinctions to be made. (Christiane Paul)

NFTs give museums the opportunity to open up the criteria of what we imagine could become a significant contribution to art history. What captivated us at the Centre Pompidou is the wide range of players in this field, redefining the game. (Marcella Lista)

Why should an institution that isn’t going to resell the work be worried about this thing called ownership that most humans are obsessed with? (Kevin Abosch)

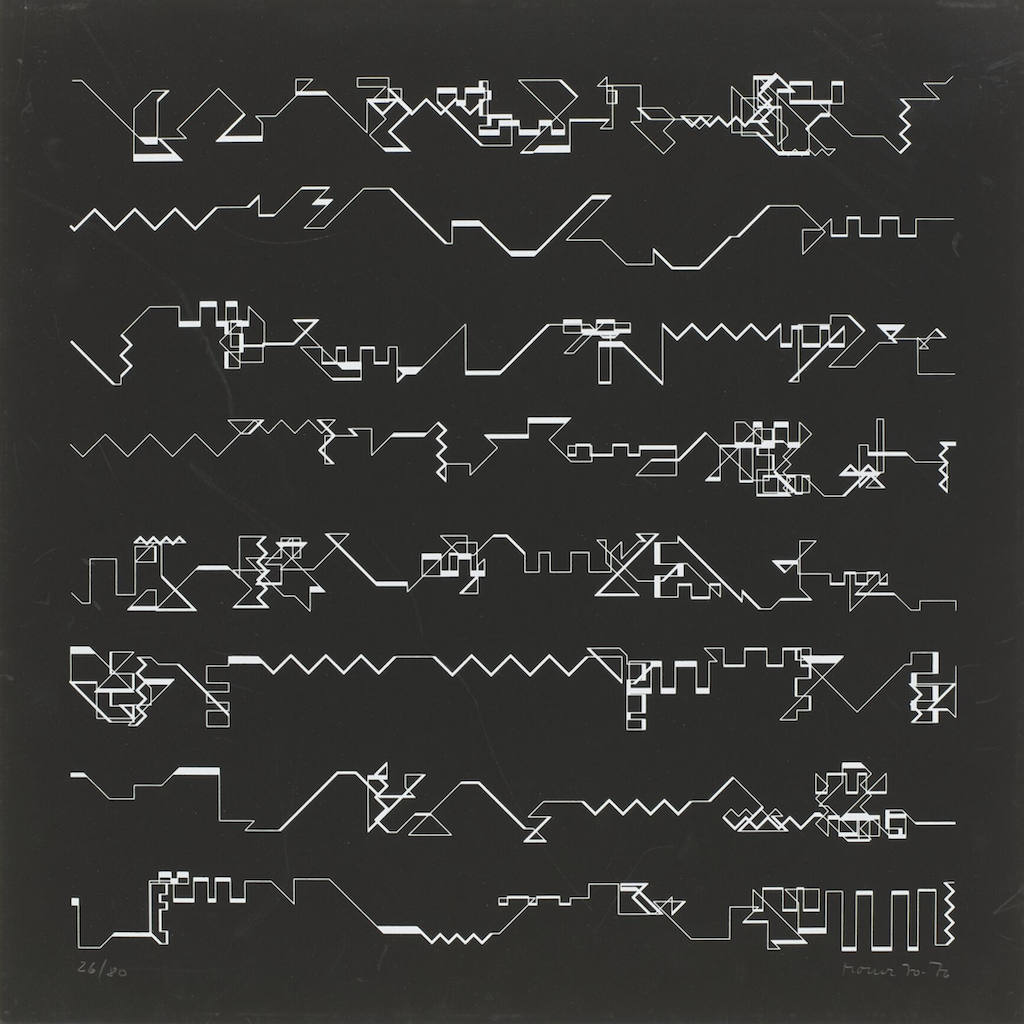

In the case of Larva Labs’ Autoglyphs (2019), the artists said to us “well, you can either display the work on a screen, but you also print it, and exhibit it in the form of a wall drawing.” There’s a new life to the work once it crosses the border of the museum, a new set of possibilities and encounters with audiences IRL, as well as with artworks from other traditions. (Marcella Lista)

Centre%20Pompidoun%20MNAM-CCI%2C%20HELENE%20MAURI%20(21).jpg)

The direction that the collection is moving in is very much about addressing some of those gaps — who’s not in there? Why are they not in there? It’s not bound by certain constraints in terms of the media. (Melanie Lenz)

One needs to make a distinction between design, in this case data visualization that falls more into the category of graphic representation, no matter how beautiful, and data visualization that becomes a metanarrative about cultural beliefs and knowledge. That, to me, would push it more into the art corner, but ultimately, we make those decisions on a case-by-case basis. (Christiane Paul)

Kevin Abosch: I think a number of artists are hanging their hat on the legacy of other artists, as if it’s some kind of surefire branding mechanism.

With thanks to Diane Drubay, Roger Haas, and Georg Bak.

Kevin Abosch is an artist whose work explores identity, value, and the human condition through photography, film, painting, and generative systems. His projects have been exhibited internationally at museums and biennials including the National Gallery of Ireland, the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg; the National Museum of China, Beijing; Jeu de Paume, Paris; ZKM Karlsruhe; and the Venice Biennale. His recent work investigates synthetic photography and artificial intelligence as means of interrogating ethics. He lives and works in Paris, and teaches at the University of Applied Arts Vienna.

Melanie Lenz is curator of Digital Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum where she is responsible for developing the V&A’s digital art collection. She has organized multiple exhibitions, most recently co-curating “Patric Prince: Digital Art Visionary” (2023-2024). She co-edited the book Digital Art: 1960s to Now (2024) and the forthcoming publication Emergence: Art and Generative Systems. She has also published on diverse topics including generative art (2024), early computer art in Latin America (2018), gender, art, and technology (2014), and collecting and conserving digital art (2011). Based in London, she is a judge for The Lumen Prize for Art and Technology and is a panel expert for the National Archives.

Marcella Lista is the Head Curator for the New Media Collection at Centre Pompidou.

Christiane Paul is Curator of Digital Art at the Whitney Museum of American Art and Professor Emerita at The New School. She is the recipient of 2023 MediaArtHistories International Award and the Thoma Foundation’s 2016 Arts Writing Award in Digital Art. Her latest books are Digital Art (4th ed., 2023) and A Companion to Digital Art (Blackwell-Wiley, 2016). At the Whitney Museum she curated exhibitions including “Parting Worlds / Hyundai Terrace Commission: Marina Zurkow” (2025), “Harold Cohen: AARON” (2024), “Refigured” (2023), and “Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art 1965-2018” (2018/19), and is responsible for artport, the museum’s portal to Internet art. Other curatorial work includes “Chain Reaction” (2023), “DiMoDA 4.0 Dis/Locatio” (2021-23), and “The Question of Intelligence” (Kellen Gallery, The New School, New York, 2020).

Alex Estorick is Editor-in-Chief at Right Click Save.

This is an edited version of a conversation hosted by ArtMeta at The Digital Art Mile, Basel on June 18, 2025.