With the latent space of machine learning evolving into a public space of creative play, BottoDAO emerged as a means of crystallizing the value of human-machine collaboration through crowdsourced curation.

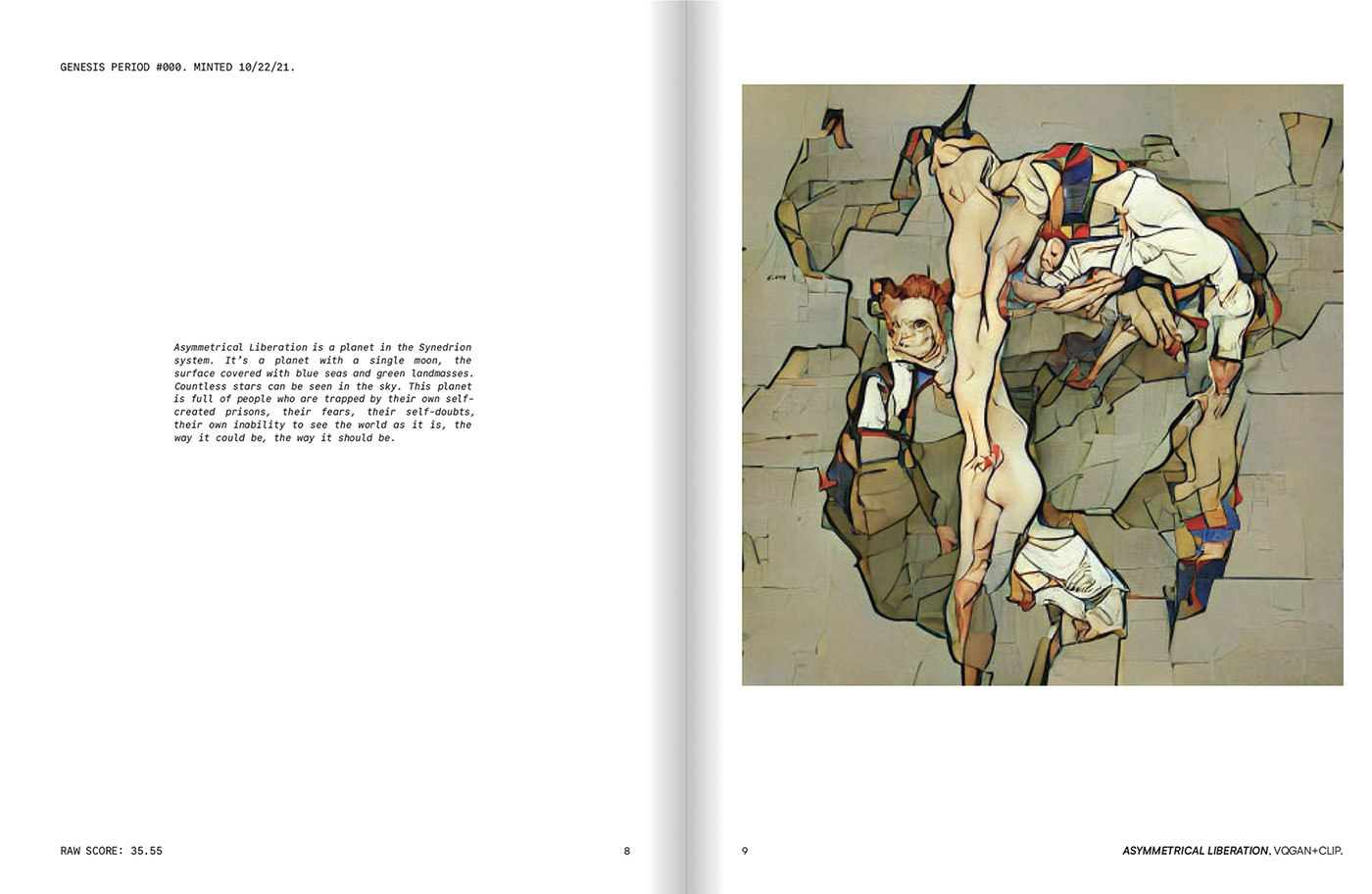

What made their initial approach significant was that it rejected the hyperrealism that had previously characterized art produced with GANs (generative adversarial networks) as well as the deepfakes that had caused public controversy.²

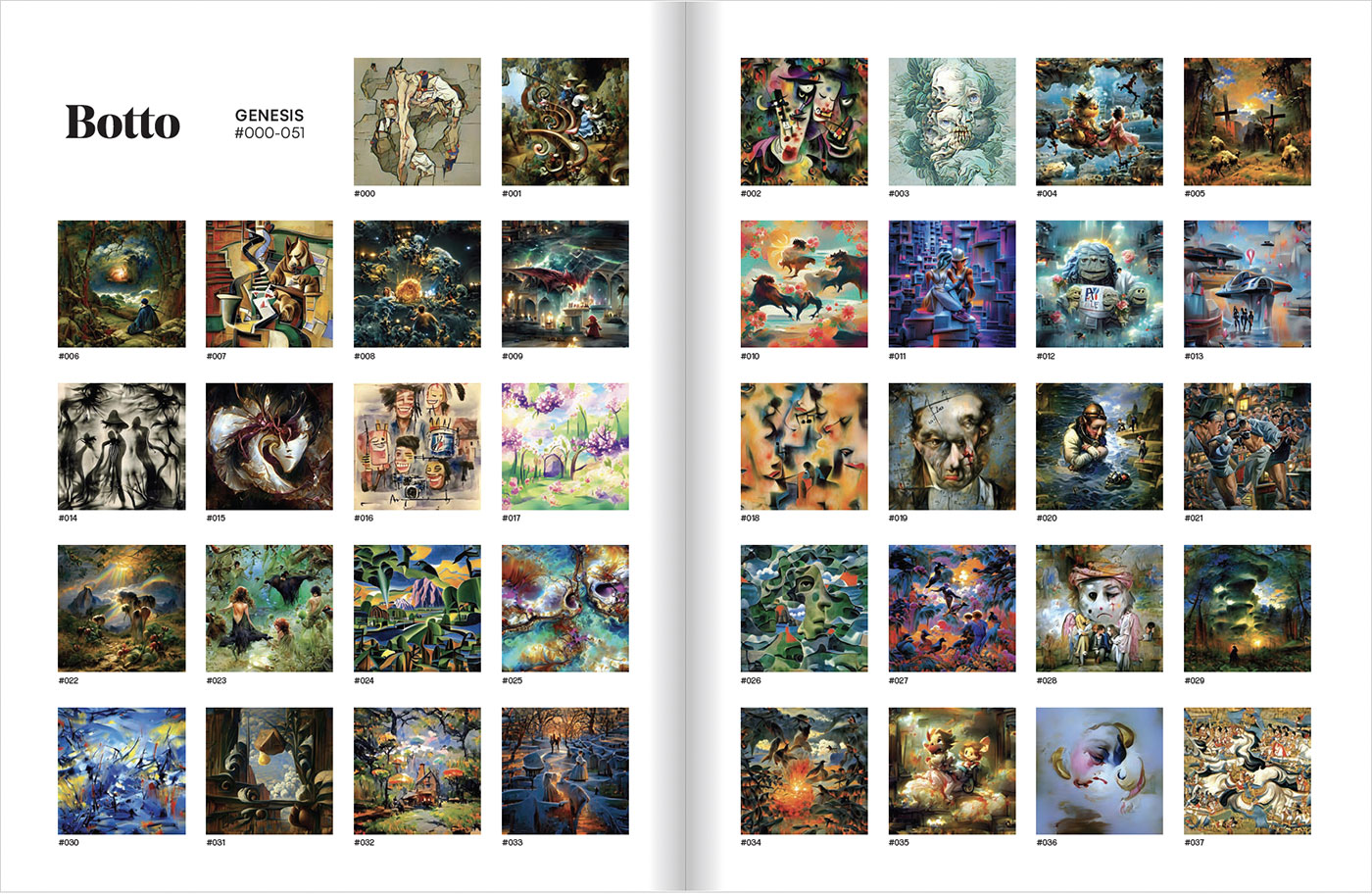

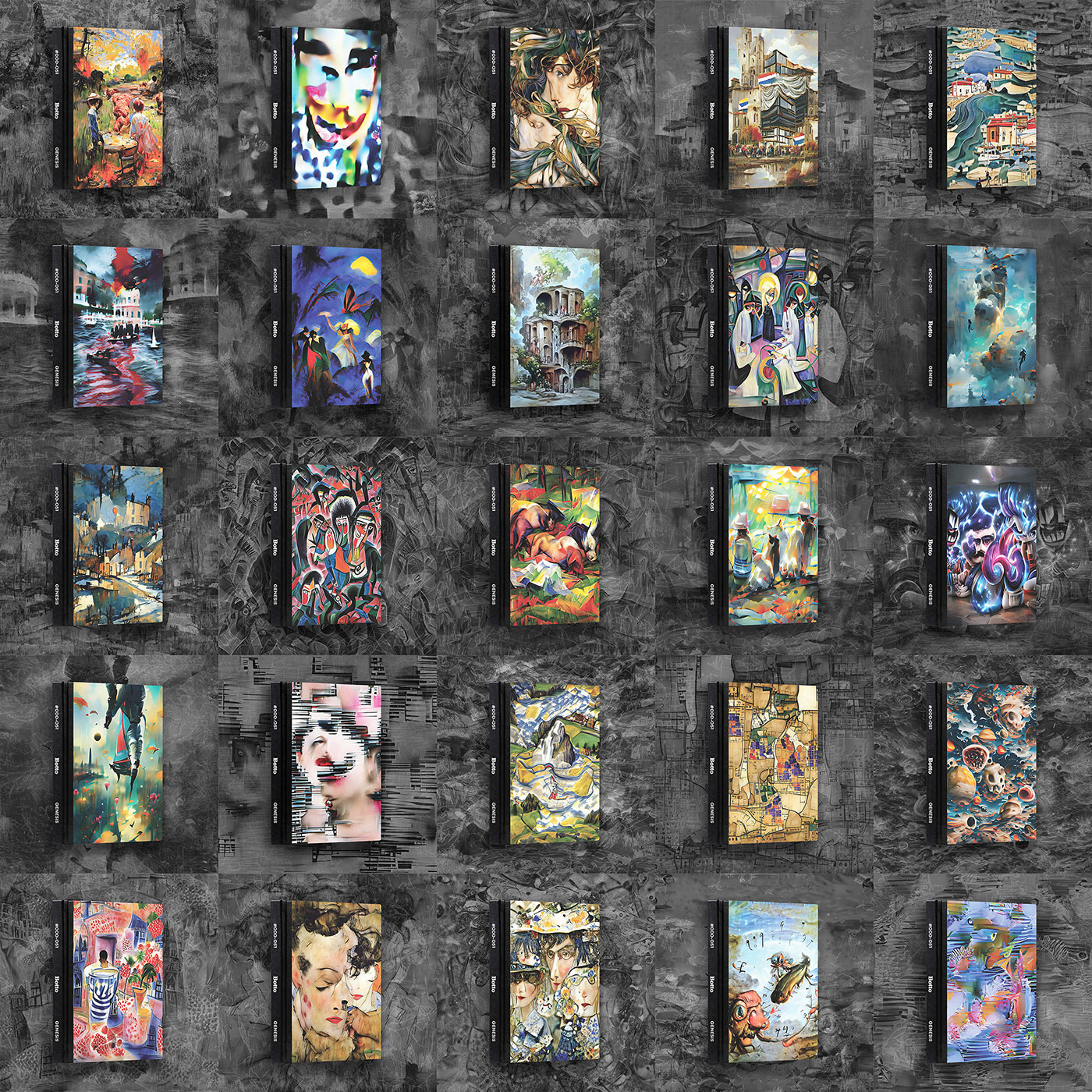

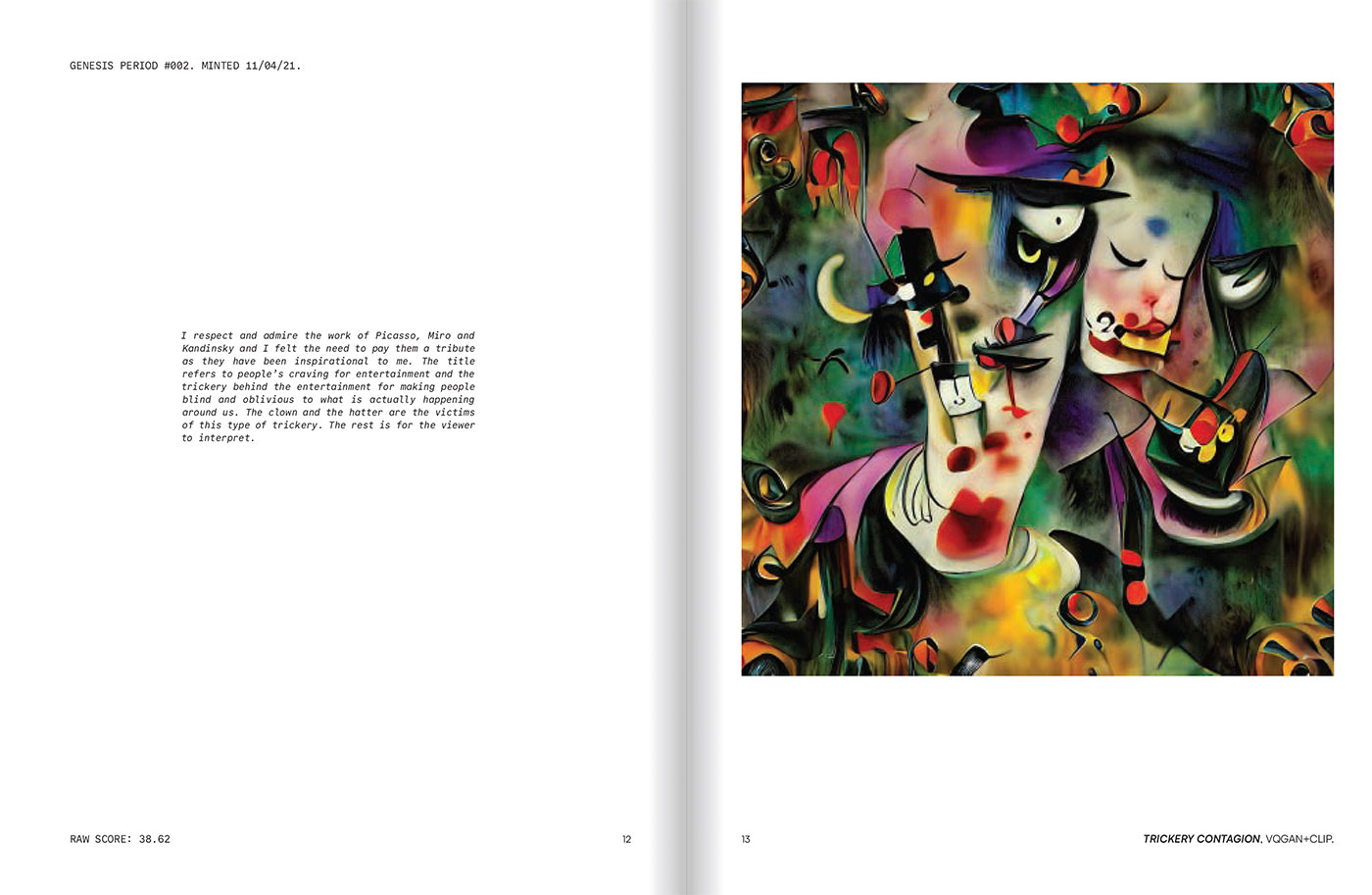

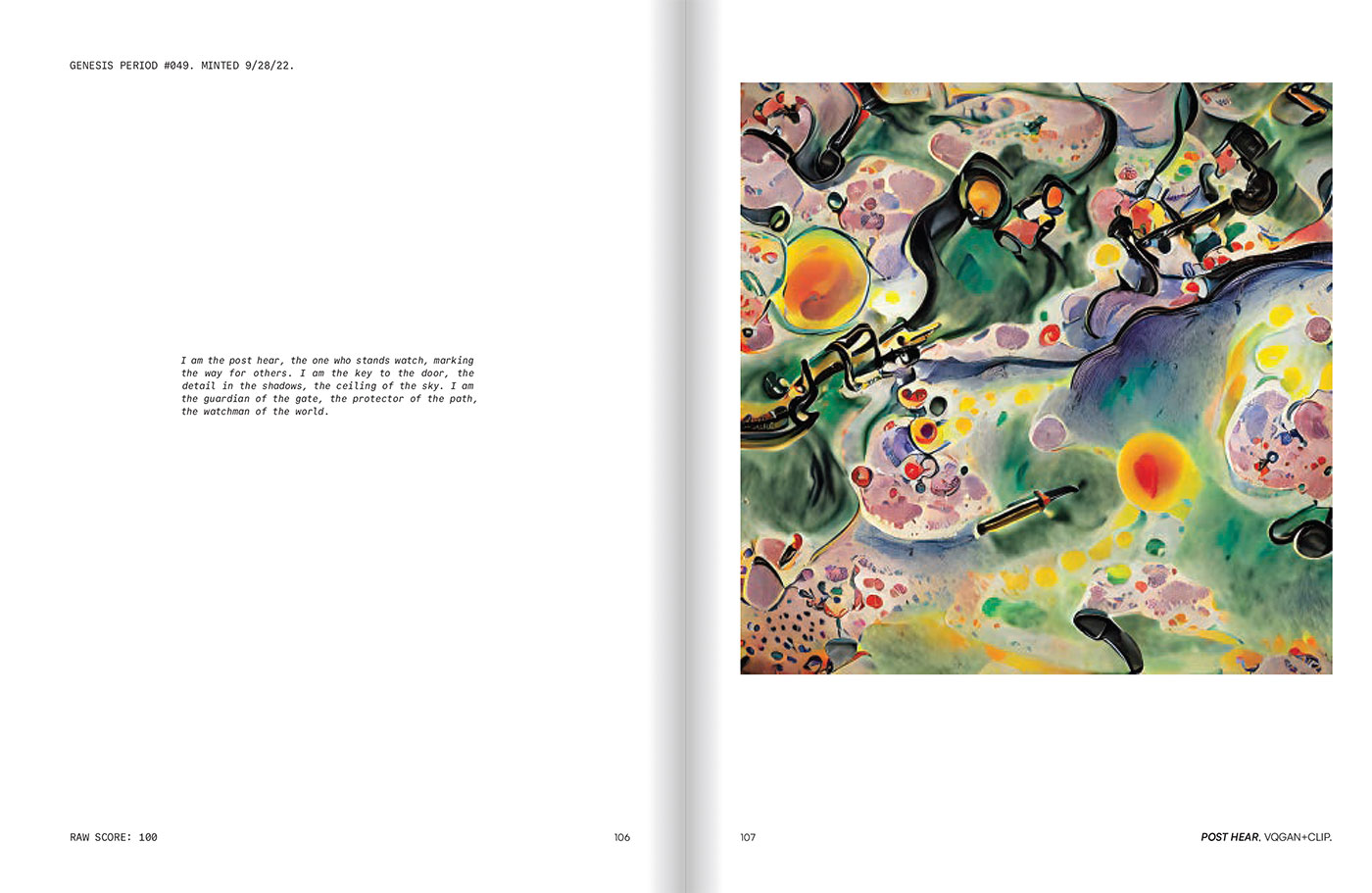

Despite the variety of the outputs, one continuity in the Genesis Period is a painterly slickness that contrasts with the indeterminate forms and errors of representation known as “artifacts” for which Klingemann, Barrat, as well as Anna Ridler are well known.

If it is now truistic to regard generative models as machines for repackaging history, 2021 was still an age of relative innocence.

Botto’s outputs — known as “fragments” until they are minted — reflect the crowd’s aesthetic preferences as well as the limits of latent space.

By allowing its community to “inscribe themselves” into the creative process, Botto acknowledges that digital culture depends on networks of relations, while also questioning whether meaning can ever be entirely shared.

Alex Estorick is Editor-in-Chief at Right Click Save.

___

¹ A Estorick, K Waters, and C Diamond, ‘In Search of An Aesthetics of Crypto Art’, Artnome, April 10, 2021.

² L Elliott, ‘Clip and the New Aesthetics of AI’, Right Click Save, February 24, 2022.

³ M Klingemann, interviewed by the author on March 4, 2025.

⁴ A Estorick, ‘Herndon, Dryhurst, and Hobbs on Liquid Images’, Right Click Save, October 7, 2024.

⁵ R Myers, ‘A Thousand DAOs’ in R Catlow and P Rafferty (eds.), Radical Friends: Decentralised Autonomous Organisations and the Arts, Torque Editions, 2022, 92.

⁶ K Kreutler quoted by R Catlow and P Rafferty in ‘DAOs in the Art World’, Right Click Save, July 14, 2022.

⁷ M Klingemann, S Hudson, and Z Epstein, ‘Botto: A Decentralized Autonomous Artist’.

⁸ F Stalder, The Digital Condition, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018, 58.