“Suzanne Treister: Prophetic Dreaming” is at Modern Art Oxford until April 12, 2026, and is curated by Jessie Robertson, Antonia Blocker, and Amy Budd. It will be presented at Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, Poland, in 2026, and will be reimagined by MIMA, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, UK, in 2027.

I’d like to inspire critical and outside-the-box thinking, ethical thoughts/actions and mystical revelations.

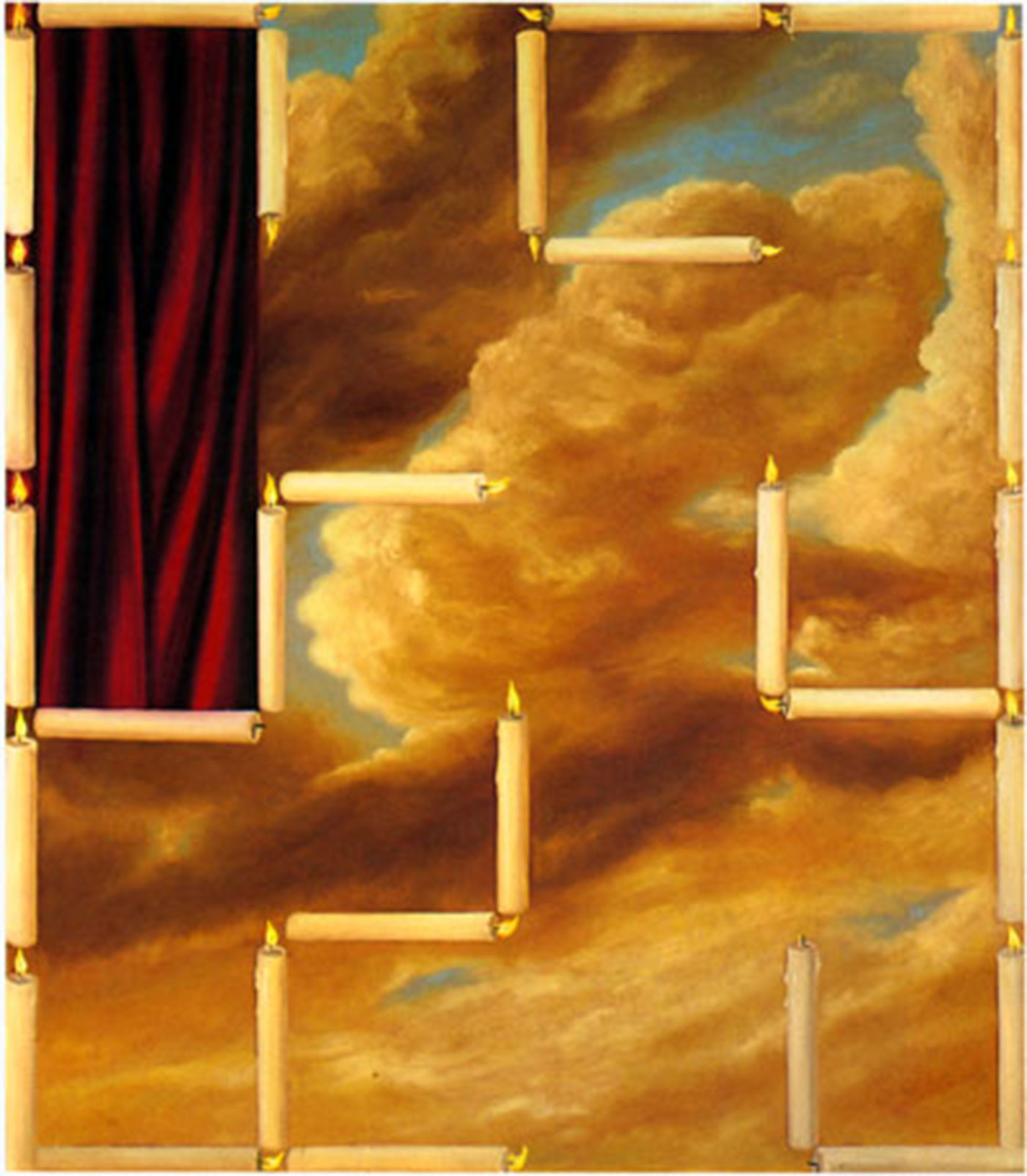

I saw the violent subject matter of the videogames and interactive technology as a possible sign of a much deeper, developing culture within civilization, which could lead to other potential uses of new technologies, perhaps military, as well as for hypothetical positive uses or even spiritual experiences. My 1980s paintings try to explore these ideas.

Then when I moved to Australia without my Amiga I made SOFTWARE (1993-94), a series of imaginary software packages out of cardboard, paint and floppy discs, anticipating what we now call apps; then a series of paintings about virtual reality; and then in 1995 I made my first website.

For me it’s a Kabbalistic process.

There is always the chance that reality is actually elsewhere, out of sight of science or mystical ideas or of any human understanding.

It comprises supposed manifestations of either a survivor of the human race, on earth, in space, on a new planet or parallel universe, or an artificial superintelligence (ASI), perhaps transmitted through quantum technology to us on Earth at our moment in time.

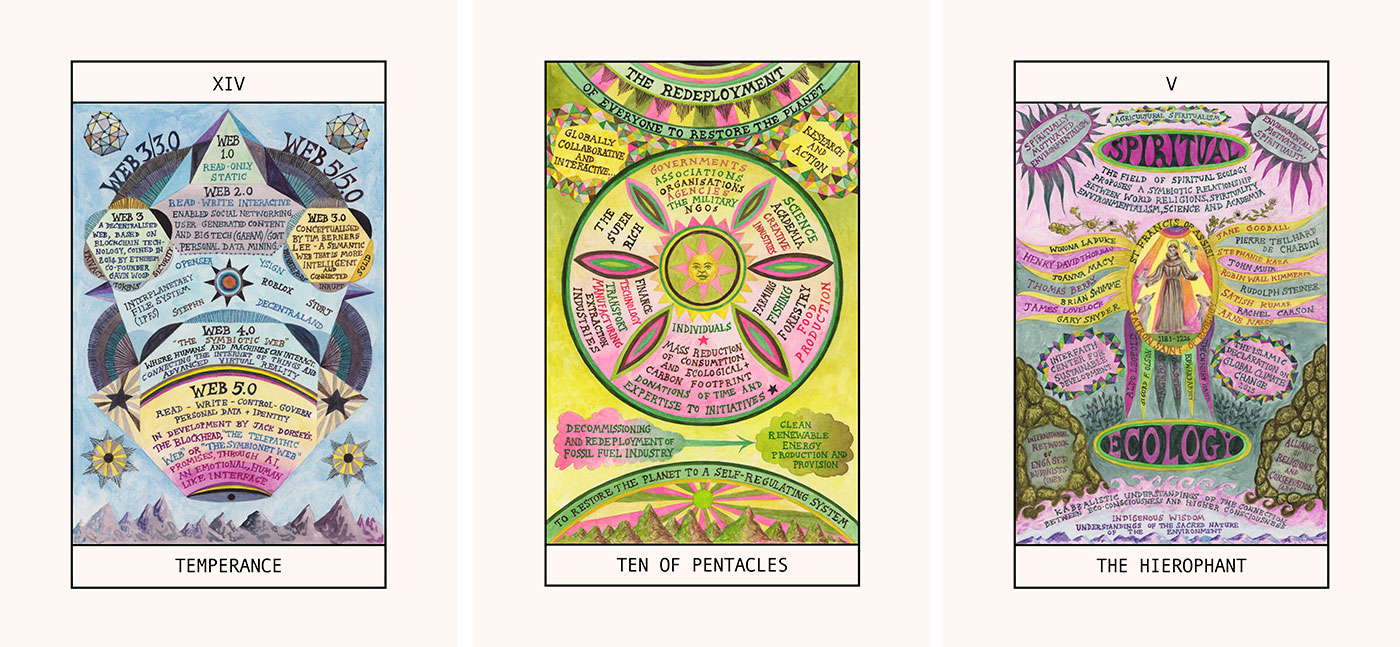

Mystical Earth System Science understands, analyses, and interacts with the planet as a holistic complex system, in an attempt to address the climate crisis by working towards a return to a self-regulating planet.

I used these structures for my tarot decks, specifically deploying the format of the tarot to allow audience participation in the engendering of possible new ideas for better futures.

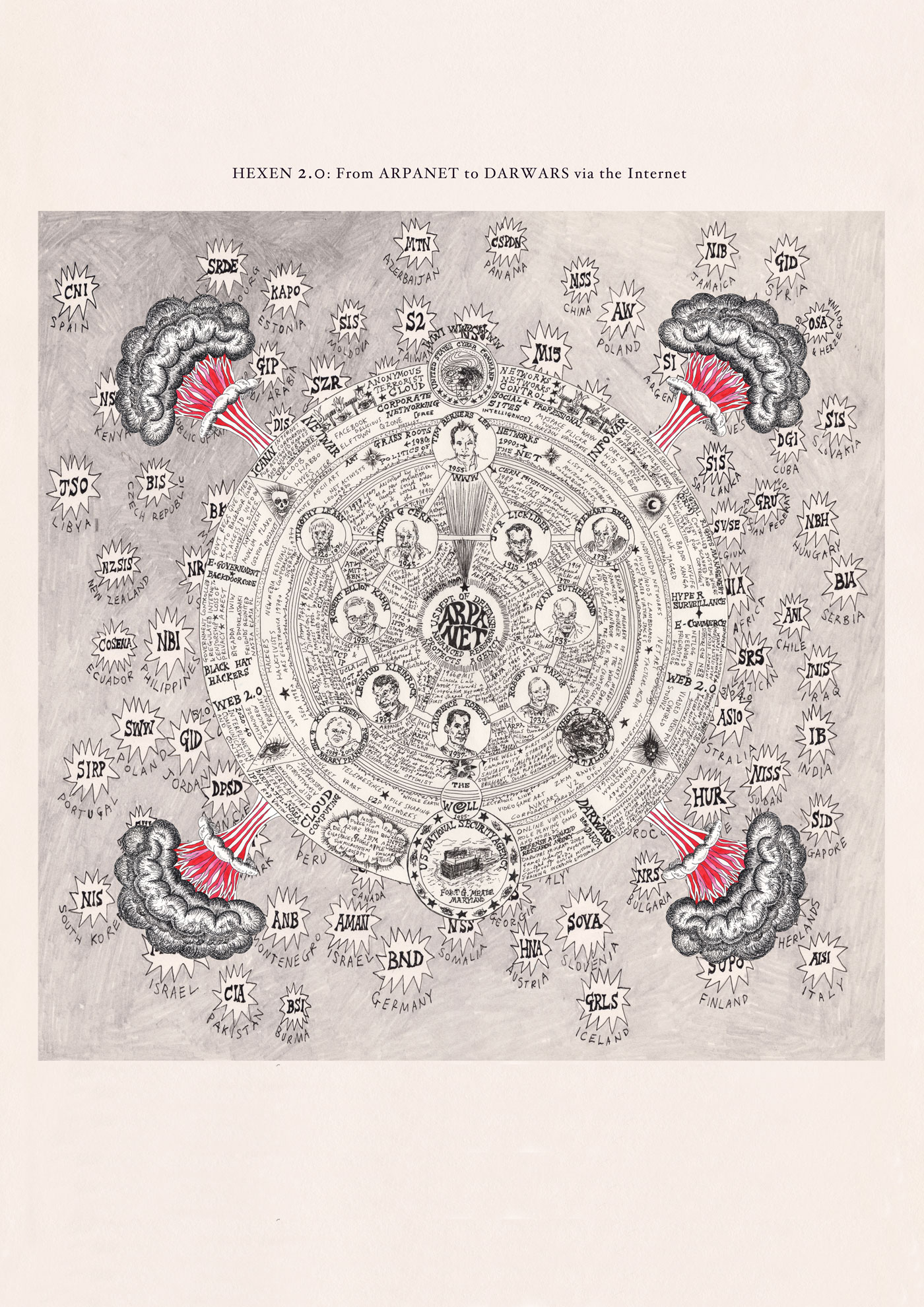

Not just WWII but all future systems of control and political and military dominance. That’s what drives a lot of my work.

There is no point complaining without proposing alternatives. At a recent HEXEN 5.0 reading the future card came out as THE HANGED MAN — Countercultures of Refusal and Renewal.

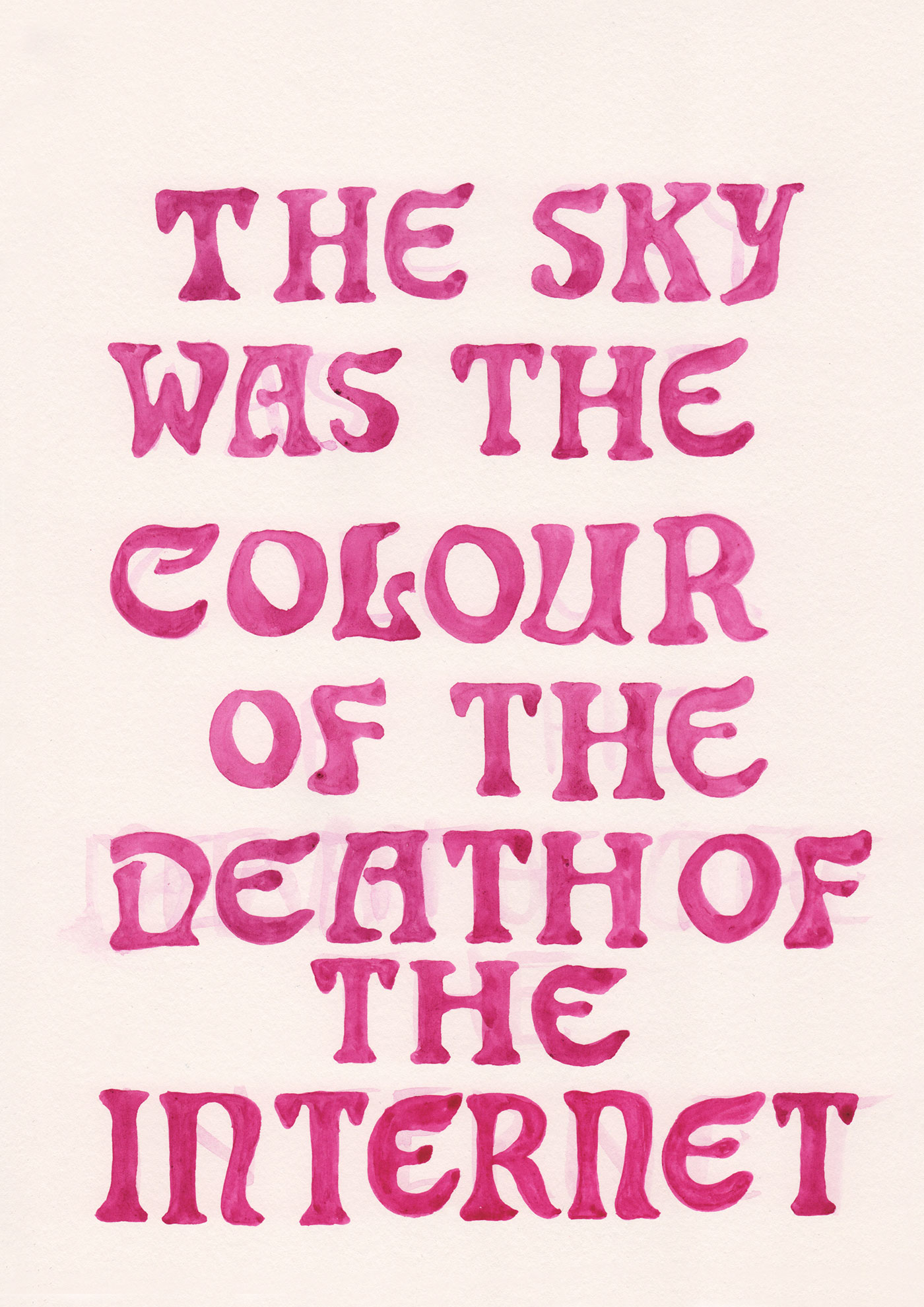

ST: Venus on TV on the Moon (1986) was a premonition of the Interplanetary Internet.

I was largely showing in the new media art world through the 1990s, exhibiting in festivals where it was a given that one was a new media artist.

I also feel good about making books about my projects as they can reach broader audiences than exhibitions, and perhaps books will outlive the internet. Until the day that everything burns.

Suzanne Treister (b. 1958, London, UK) studied at St Martin's School of Art, London (1978-1981) and Chelsea College of Art and Design, London (1981-1982) and is based in London and the French Pyrenees, having lived in Australia, New York and Berlin. Initially recognized in the 1980s as a painter, she became a pioneer in the digital/new media/web-based field from the beginning of the 1990s, making work about emerging technologies, developing fictional worlds and international collaborative organisations. Utilising various media, including video, the internet, interactive technologies, photography, drawing and watercolour, Treister's work has engaged with eccentric narratives and unconventional bodies of research to reveal structures that bind power, identity and knowledge. Often spanning several years, her projects comprise fantastic reinterpretations of given taxonomies and histories that examine the existence of covert forces at work in the world. An ongoing focus of her work is the relationship between new technologies, society, alternative belief systems and the potential futures of humanity.

Recent solo and group exhibitions include: “Suzanne Treister: Prophetic Dreaming”, Modern Art Oxford (2025); 5th Industrial Art Biennial, Croatia; 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale, Korea; The Warburg Institute, London (2025); Tate Modern, London; Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna; United Nations, New York (2024); 14th Shanghai Biennale; Museion Bolzano, Italy; Centre Pompidou-Metz; Helsinki Biennial, Finland; ARoS Kunstmuseum, Denmark; P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York (2023-4), High Line, New York; Plateforme 10, Lausanne; Hayward Gallery Touring; Albertinum, Dresden; Somerset House, London; Palace of Culture and Science, Warsaw (2022).

Hannah Redler-Hawes is a curator known for her pioneering work in arts-led interdisciplinary and digital projects. She has been commissioning and curating digital and media art since the early 1990s, including the first interactive software and neural net-based installation art to be acquired by the national collections. Between 1999 and 2014 she led a contemporary art programme at Science Museum London, where she had the privilege of premiering Suzanne Treister’s Hexen 2.0 in 2012. Hannah’s curatorial practice convenes outstanding artists, scientists, technologists, experts by experience and world-class arts, science and cultural organisations to create award-winning new artworks, exhibitions, programmes, research projects and events across disciplines, but specialising in participation, interaction and the emerging fields of data and AI. Her work champions the essential roles of artists alongside researchers, educators and activists in imagining alternative modes or spaces for people and other living beings to live well and in finding ways for ethical and equitable practices to take hold across technologies. She combines her independent practice with her role as an Open Data Institute (ODI) Associate, directing Data as Culture art programme. Hannah trained as a painter at Camberwell and Norwich Schools of Art and in curating contemporary art at the Royal College of Art. In 1993 she co-founded one of London’s first interactive multimedia software companies with other artists, designers and friends.