Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, “The Delusion”, is at Serpentine North Gallery, London, until January 18, 2026.

The work asks the biggest questions. How do we embed soul in the digital world? (Bettina Korek, CEO, Serpentine Galleries)

Through the artist’s poised, ebullient coaxing, a set of notes from an untrained collective somehow melded into a resonant, visceral chord: at its core a euphonious, richly populated, major fifth.

In line with the artist’s taste for gaming lore, visitors are given an engaging 12-page newsprint zine-like program for the exhibition, with reproductions of some of the artist’s 22 original drawings, created “in reaction” to news events over the past year and hung through the show and its four participatory galleries.

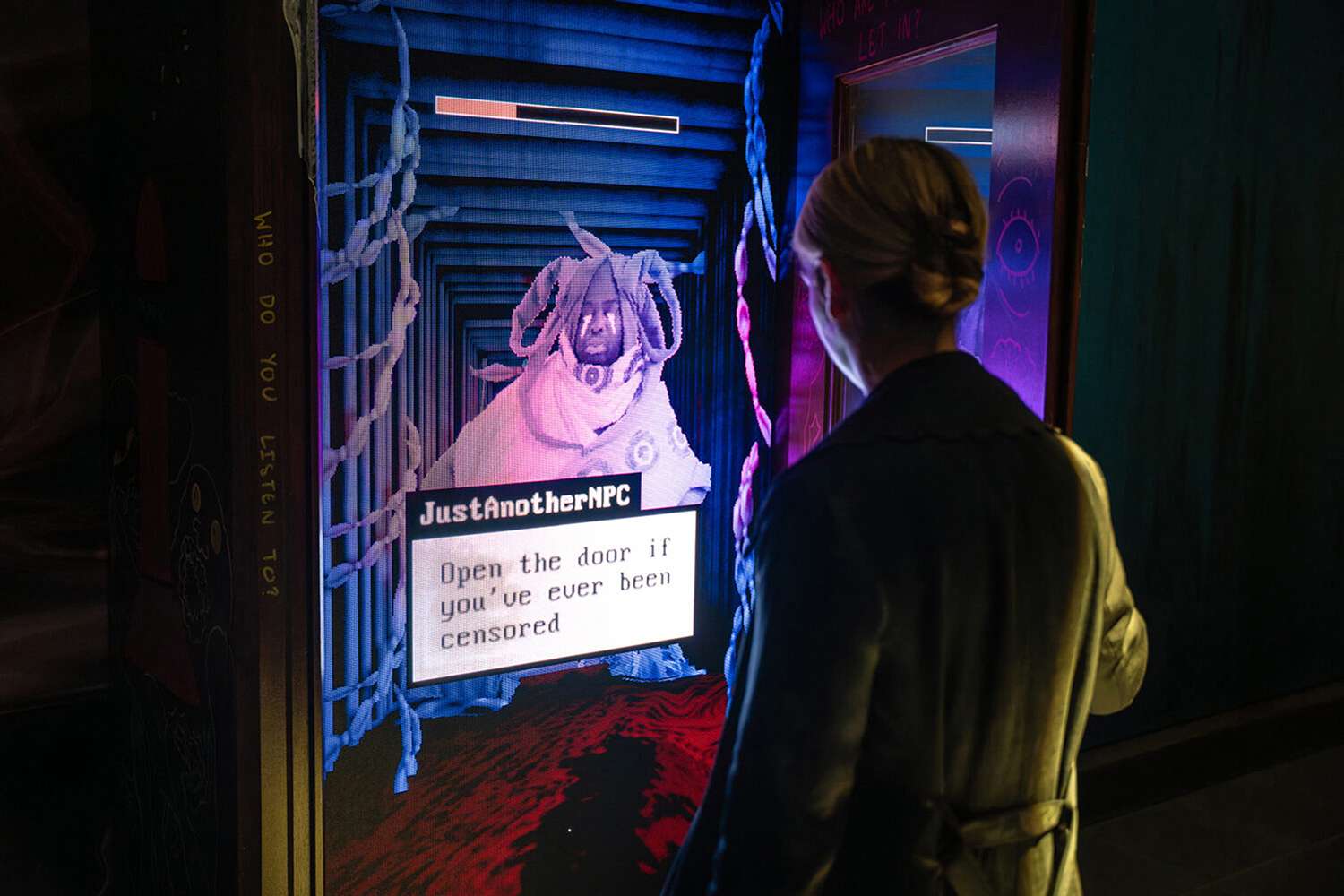

This game references one of Brathwaite-Shirley’s favourites, Doom (1993) — a point-and-shoot game that caused moral panic, and outrage in the US Congress, on its release. As a child she read the game’s instructions so much (before she got to play the game) that she used to dream in Doom’s graphics.

Brathwaite-Shirley also names Hideo Kojima for showing “how games can start becoming meta narratives. They comment on who you are, what you’re doing in the game, your morals, your lack of morals within a space you think doesn’t exist.”

I don’t think we give enough credit to women in tech as literal pioneers of new ideas and pioneers of new spaces and new ways to use it […] women are driving tech in art and they’re just not getting the recognition for it right now. (Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley)

They made an untraditional archive, filled with nonsense, fiction, and magic, and built a game with a simple controller, with just three buttons, so that all demographics could play.

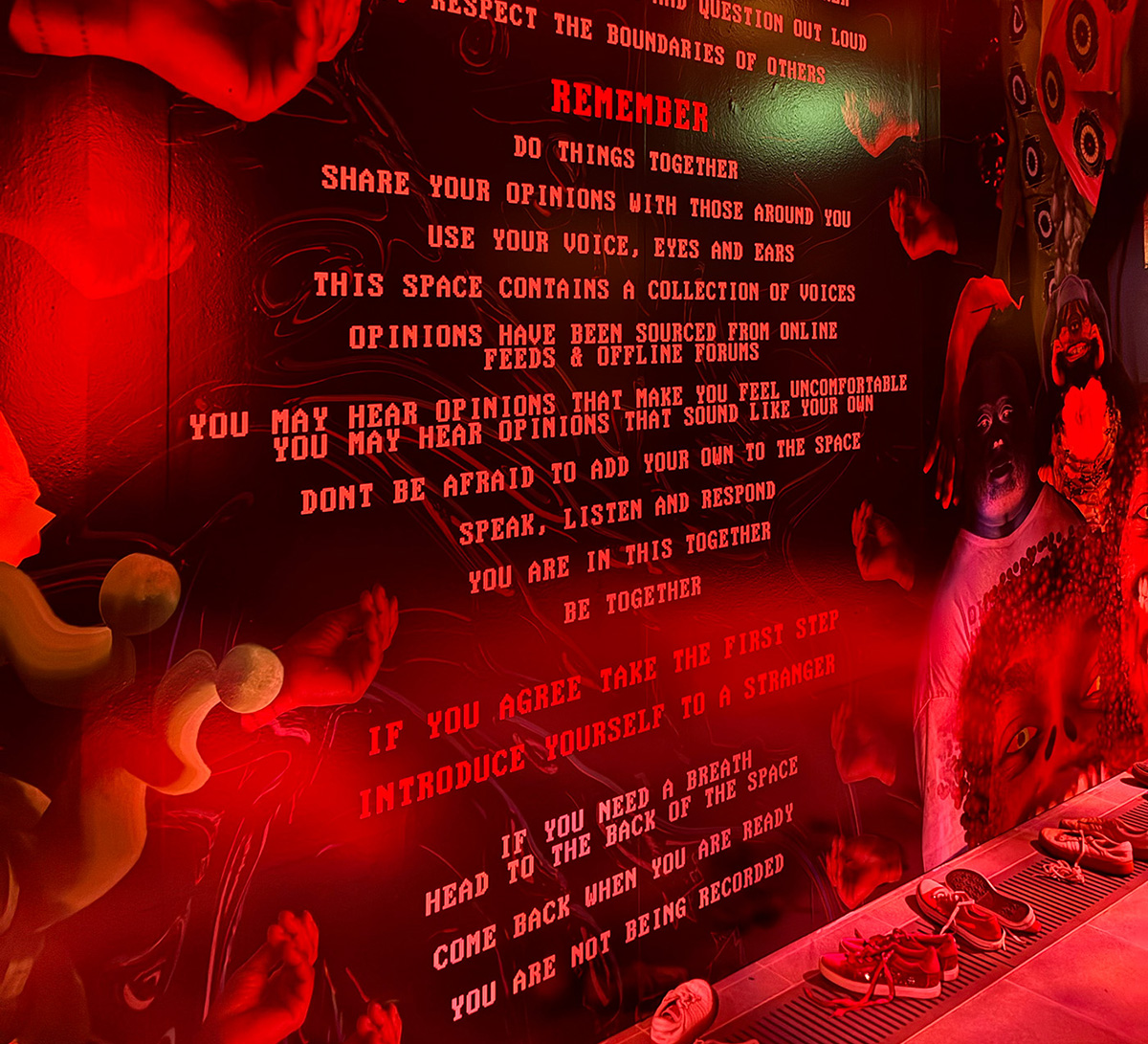

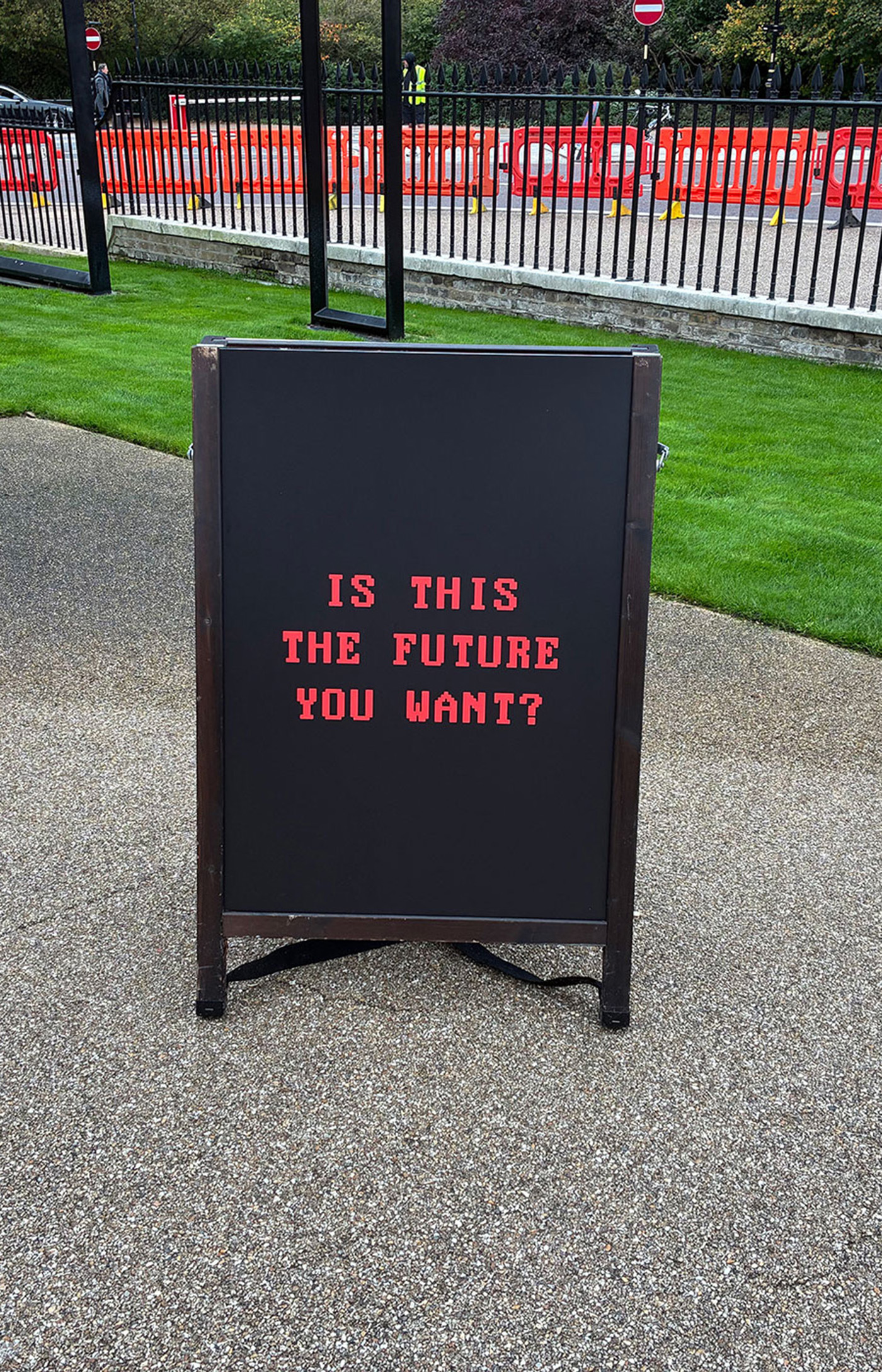

“The Delusion” is my Community Center in which games help mediate difficult conversations and help you get to why you’re thinking the way you do and what your opinion might be. It’s not a place to tell you what’s right or wrong. It’s not a place to judge you. (Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley)

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley lives and works between Berlin and London. Working predominantly in animation, sound, performance, and video-game development, and with a background in DIY print media and activism, the artist focuses on intertwining lived experience with fiction to imaginatively retell and archive the stories of Black Trans people. Danielle utilizes interactive technologies to create participatory spaces that challenge traditional narratives and encourage active engagement. Their projects often take the form of immersive video games, where players navigate choices that confront their assumptions and biases, fostering conversations about identity, privilege, and systemic oppression.

Danielle has presented recent solo exhibitions at institutions such as LAS Foundation, Halle am Berghain, Berlin (2024); Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona (2024); Studio Voltaire, London (2024); Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève (2024); SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah (2023); Villa Arson, Nice (2023); HAU Hebbel am Ufer, Berlin (2023); FACT, Liverpool (2022); Project Arts Centre, Dublin (2022); Skänes konstförening, Malmö (2022); Arebyte Gallery, London (2021); QUAD, Derby (2021); Focal Point Gallery, Southend-on-Sea (2020). Their work has been included in group exhibitions at institutions such as Art Museum at the University of Toronto (2024); National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Seoul (2023); Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York (2023); Das Centre Pompidou, Metz (2023); Julia Stoschek Foundation, Berlin (2022); Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo (2021); Les Urbaines, Lausanne (2019); and Barbican, London (2018). Her/their work has been the subject of screenings and performances at institutions including Tate Modern, London (2024, 2020); MoMA, New York (2023); DePaul Art Museum, Chicago (2023); Serpentine, London (2022); Spike Island, Bristol (2022); and South London Gallery (2022). Permanent collections include the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Louis Jebb is Managing Editor of Right Click Save.