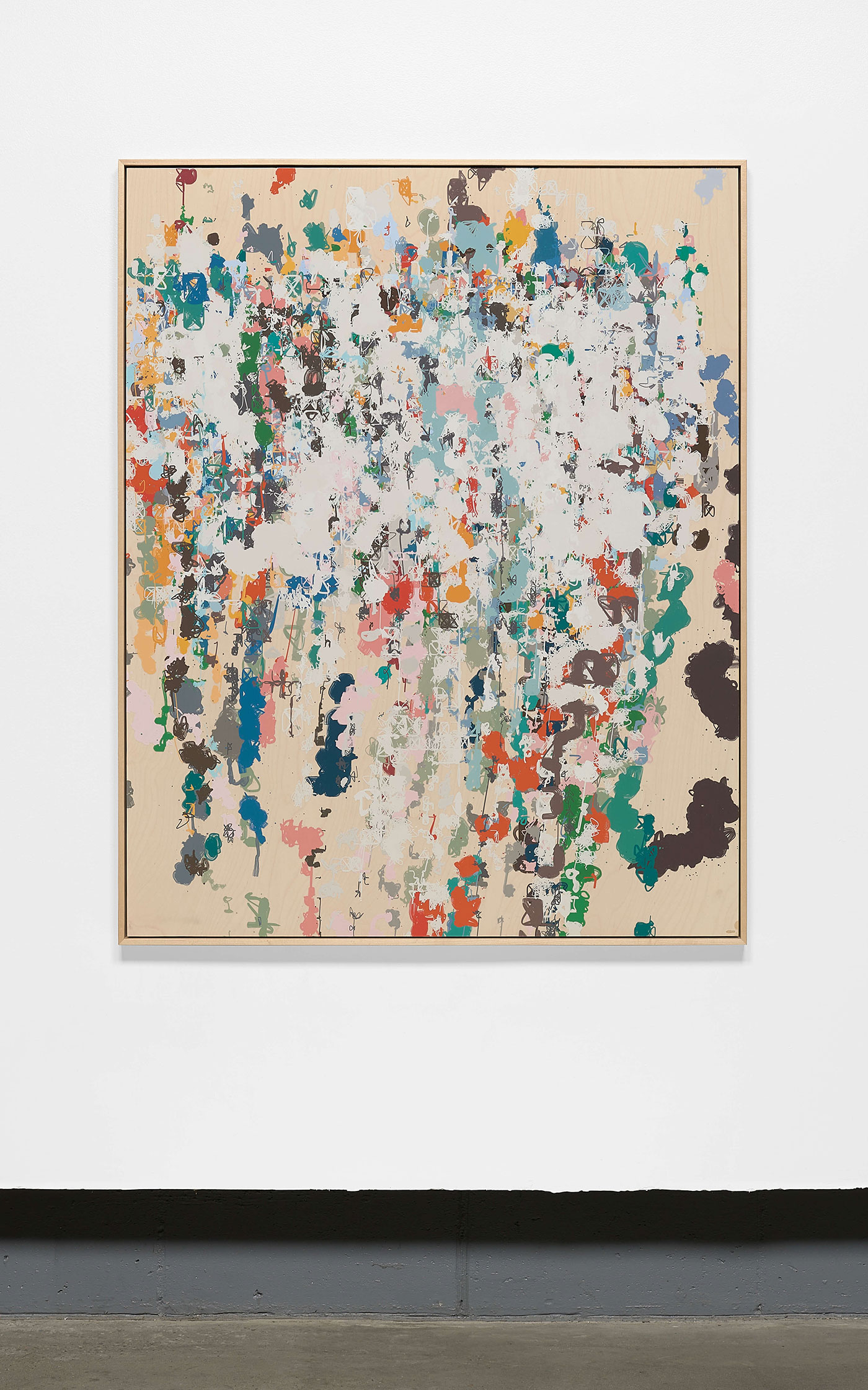

The artist Tyler Hobbs is showing a new generative series, From Noise, (2025) with SOLOS gallery, as part of the first iteration of the Zero 10 section, devoted to art of the digital age, at Art Basel Miami Beach (December 3-7, 2025).

Hobbs talks about how ingrained memories of the work of gestural painters such as Mitchell and Twombly informed the creation of From Noise, where he was concerned with the “translated gesture” — taking a gestural, spontaneous, brushstroke from canvas to algorithm — and the potential for what he terms “maximalism” in generative art.

I can attack dense, complicated, ideas in a way that a painter can’t; at least not on the same timescale and not in the same way. I was curious about how the generative model of working interacts with a maximalist idea and maximalist aesthetics. From Noise is an exploration of [the] “translated” gesture, applied maximally.

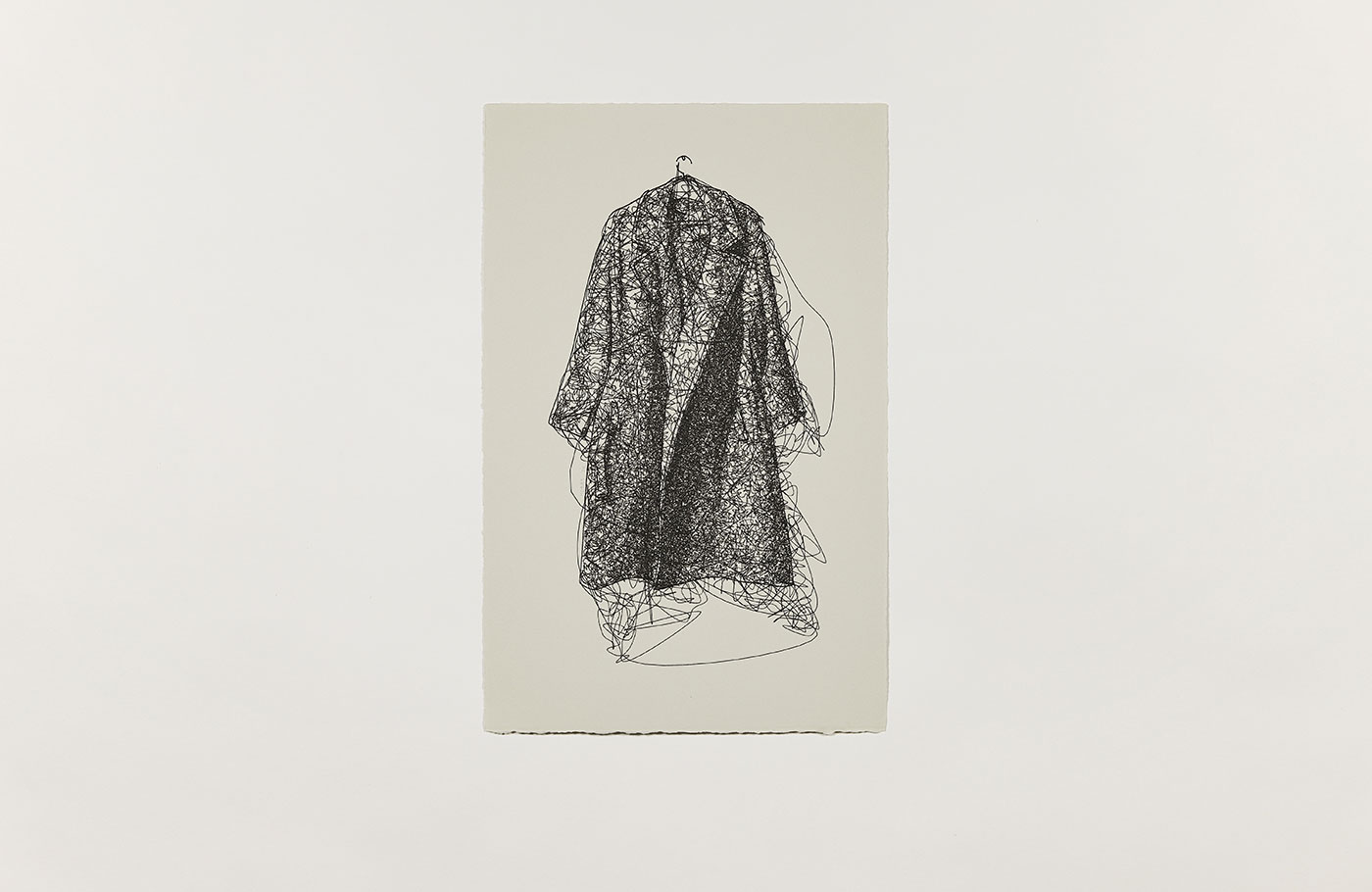

The algorithm has taught me how to introduce control in the physical world and the physical world has taught me how to introduce chaos into the algorithmic world.

Something that I find very inspiring or appealing about paints and brushes is that they leave very rich marks [but] it is not fully controlled. It doesn’t always go exactly where you intend it to.

I tend to enjoy [it] when the work lands in this space that is somewhat ambiguous, that has qualities of both the analog world and the digital world or qualities of paint and of algorithms. From Noise has a bit of both worlds inside of it.

Many digital [and] generative artists are used to most of their work being consumed on somebody’s telephone as they’re scrolling through Instagram.

The advent of Art Blocks and the AB 500 brought the entire scene together into one place.

There is something about artists building off each other, challenging each other, developing ideas together. Art Blocks did that in an amazing way.

My thoughts about the relationship between the digital and the physical, [and] my capacity for exploration versus deep diving on one subject [have] changed over time as I’ve matured as an artist.

I’m always interested in moving forward and not particularly interested in repeating myself.

I did not go back and look at the work of those artists while working on this series because I don’t want to do an imitation. It’s almost better if it’s a memory of an artist or a work that has gone through the filter of your own mind. That is the best way that an influence can shape your work.

Those are things where a 30-minute chunk of time just isn't enough to sink your teeth into something. I like to have at least a whole day, if I can, if not several whole days in a row, to really work on new artwork.

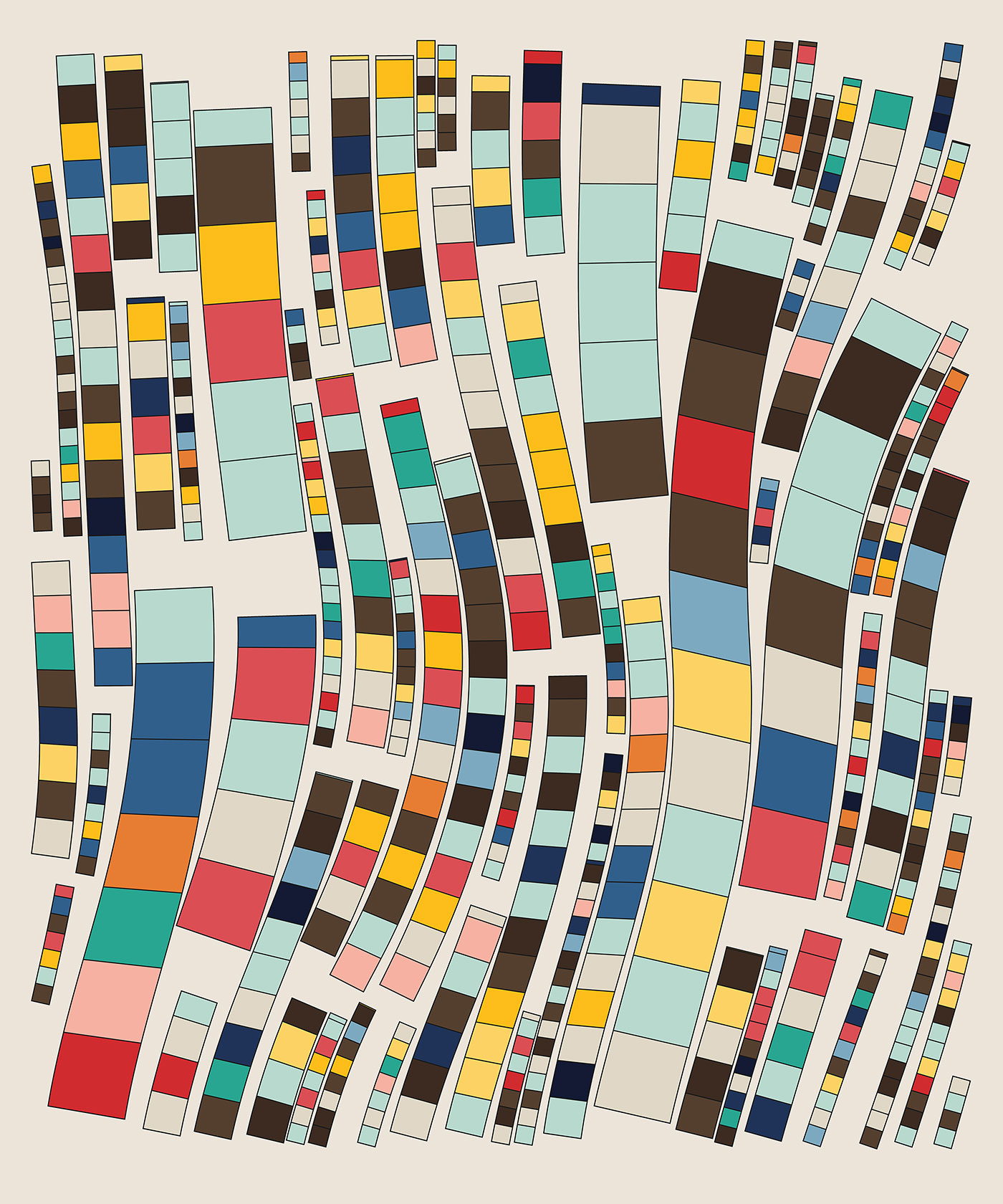

Tyler Hobbs is a visual artist from Austin, Texas, who works primarily with algorithms, plotters, and paint. His artwork focuses on computational aesthetics, how they are shaped by the biases of modern computer hardware and software, and how they relate to and interact with the natural world around us. Hobbs develops and programs custom algorithms that are used to generate visual imagery. Often, these strike a balance between the cold, hard structure that computers excel at, and the messy, organic chaos we can observe in the natural world around us.

Hobbs’s work has been exhibited internationally, with recent solo exhibitions at Unit in London and Pace Gallery in New York City. His algorithmic art has been included in numerous auctions by leading auction houses such as Christie’s, Phillips, and Sotheby’s. Notable public institutions holding his work include the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Louis Jebb is Managing Editor at Right Click Save.